The 14th Amendment’s tortuous relationship with American Indians

The 14th Amendment makes all persons born or naturalized in the United States citizens, with equal protection and due process under the law. But for American Indians, the amendment immediately excluded most of them, and it took decades of laws and legal fights to make full citizenship a reality.

Editor’s note: The AP Style guide says that American Indian and Native American are interchangeable terms for the indigenous people of North America. We used American Indian, the previous preferred AP style, for consistency.

As late as 1948, two states (Arizona and New Mexico) had laws that barred many American Indians from voting, and American Indians faced some of the same barriers as blacks, until passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, including Jim Crow-like tactics and poll taxes.

American Indians were also part of the Dred Scott decision in 1857, but in a much different way. Chief Justice Roger Taney argued that American Indians, unlike enslaved blacks, could become citizens, under congressional and legal supervision.

But in 1870, after the 14th Amendment’s ratification, U.S. Census figures showed that just 8 percent of American Indians were classified as “taxed” and eligible to become citizens. The estimated American Indian population in the 1870 census was larger the population of five states and 10 territories—with 92 percent of those American Indians ineligible to be citizens.

The troublesome definition of “taxed Indians” and the price of citizenship imposed on American Indians (loss of communal lands and cultural identify) dated back to another well-known Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall. And it took the Great Dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, to put the question of American Indians birthright citizenship into context, in the form of great dissent.

In what were later known as the Marshall Trilogy rulings, the Chief Justice established the precedents for how the United States legal system would deal with political and social rights for American Indians who lived in the territorial boundaries of the United States.

Marshall wrote in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia in 1831 that the Cherokees didn’t have legal standing to prevent the state of Georgia from seizing its lands.

“It may well be doubted whether those tribes which reside within the acknowledged boundaries of the United States can, with strict accuracy, be denominated foreign nations,” Marshall said about claims that the Cherokee were an independent state.

“They may, more correctly, perhaps, be denominated domestic dependent nations. They occupy a territory to which we assert a title independent of their will, which must take effect in point of possession when their right of possession ceases. Meanwhile they are in a state of pupilage. Their relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to his guardian,” he concluded.

The case didn’t preclude attempts by the federal government already underway in the 1830s, as part of an intense drive to acquire land occupied by American Indians east of the Mississippi, to grant citizenship to tribes using treaties and statutes.

Individuals were left their tribes to live outside of tribal areas fell into a different category. The Constitution in Article I said that “Indians not taxed” couldn’t be counted in the voting population of states (and slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person).

In 2000, Earl M. Maltz, Distinguished Professor of Law, Rutgers-Camden, explained one problem “taxed Indians” soon faced in an analysis of the 14th Amendment and citizenship.

“Native Americans who remained within the tribal structure were not to be considered at all in determining the number of representatives to which a state was entitled. By contrast, those who joined white society were counted fully in the basis of representation,” Maltz said.

“In general, however, even these Native Americans were not considered the full political equals of white people. Indeed, Native Americans who left their tribal communities were not even eligible for naturalization under the general naturalization statute, which allowed only white people to become naturalized citizens,” he said.

Taney confirmed in the Dred Scott decision the federal government could grant citizenship to whole Indian tribes or nations, and the issue came up a decade later as Congress considered the Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment.

In January 1866, the Senate started debate of the Civil Rights Act when Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois introduced the bill. Members of both parties were concerned that the bill’s broad language would confer citizenship on all American Indians.

Trumbull assured the senators that the bill would only grant citizenship to American Indians “who are domesticated and pay taxes and live in civilized society” and were therefore “incorporated into the United States.”

However, the act’s language was modified to limit language about birthright citizenship “Indians not taxed” to appease opposition.

When Justice John Marshall Harlan looked at these debates as he wrote his dissent in Elk v. Wilkins in 1884, the intent seemed obvious.

“It would seem manifest, from this brief review of the history of the act of 1866, that one purpose of that legislation was to confer national citizenship upon a part of the Indian race in this country—such of them, at least, as resided in one of the states or territories, and were subject to taxation and other public burdens,” Harlan said.

Harlan also said the 14th Amendment’s intention was equally clear in this area, as an extension of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

“[It} was intended to grant, national citizenship to every person of the Indian race in this country who was unconnected with any tribe, and who resided, in good faith, outside of Indian reservations and within one of the states or territories of the Union,” he said.

There was still confusion after the 14th Amendment was ratified about American Indian citizenship status in 1870, when the Senate Judiciary committee was asked to clarify the issue. The committee said it was clear, to it, that “the 14th amendment to the Constitution has no effect whatever upon the status of the Indian tribes within the limits of the United States,” but that “straggling Indians” were subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

The case of Elk v. Wilkins settled the issue for at least a few years. Elk was an American Indian who gave up his tribal affiliation, moved to Omaha, spoke English, paid taxes, and then tried to vote.

Writing for the majority, Justice Horace Gray said Elk had no claim to citizenship because he had never been naturalized as an American citizen through a treaty or statute. Even though he was born within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States, the 14th Amendment didn’t apply to Elk, who did pay taxes.

Justice Harlan strongly disagreed in his dissent.

“There is still in this country a despised and rejected class of persons with no nationality whatever, who, born in our territory, owing no allegiance to any foreign power, and subject, as residents of the states, to all the burdens of government, are yet not members of any political community, nor entitled to any of the rights, privileges, or immunities of citizens of the United States,” he concluded.

The Dawes Act in 1887 gave American citizenship to all Native Americans who accepted individual land grants under the provisions of statutes and treaties, and it marked another period where the government aggressively sought to allow other parties to acquire American Indian lands.

Another Supreme Court case in 1886 ensured that the federal government has full power and control of all lands inhabited by American Indians. And a separate act eliminated the definition of “Indians not taxed” for legal purposes.

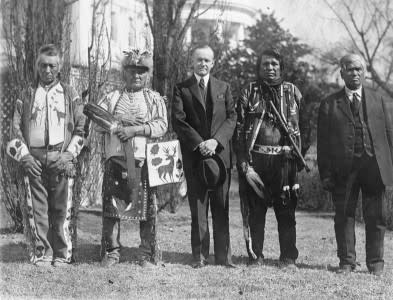

The issue of American Indian birthright citizenship wouldn’t be settled until 1924, when Congress conferred citizenship on all American Indians.

It said that “all non citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States.”

At the time, 125,000 of an estimated population on 300,000 American Indians weren’t citizens.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.

Recent Constitution Daily History Stories

Can you pass a basic 10-question quiz on the presidents?

Happy 225th Anniversary: Government begins under our Constitution