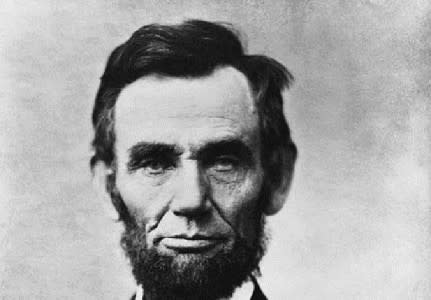

Abraham Lincoln as constitutional radical: The 13th amendment

In recent weeks, Americans have looked on as the nation’s highest court has handed down decisions seeking to reconcile fundamental questions about the scope of the U.S. Constitution.

The Constitution and its amendments are, at their core, designed to protect citizens against the actions and encroachment of government actors, with one notable exception.

The 13th amendment, ratified in December 1865, serves to limit the actions of private individuals.

By prohibiting the institution of slavery and by outlawing individual citizens from owning slaves, the legislature in the wake of the Civil War created the first constitutional provision to directly limit the rights and freedoms of American citizens.

Few could telegraph the passage of such a revolutionary amendment at the start of the conflict.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, he inherited a nation that was rapidly unraveling, largely around the question of whether slavery should extend into the western territories.

But the man who would go on to agitate for the passage of the anti-slavery amendment did not see it as his primary goal to mandate nationwide emancipation. While he opposed such westward expansion, Lincoln believed that the federal government was not constitutionally authorized to ban slavery in states where it already existed.

In 1861, when the President entered into war with the Confederacy, his aim, then, was not to disrupt the system of slavery in the South, but rather to repair the fractured nation. Still, in the early years of his presidency, as Lincoln worked toward reconciliation, he was also forced to contend with the question of how best to deal with the issue of slavery and, more broadly, with the expanding black population in the Union.

Of primary concern was the question of whether to open the Union army to African-American troops. At first, Lincoln denied black entry into the military, in part because of his anxiety over the prospect of losing northern white support. By the summer of 1862, though, with mounting deaths and desertions and declining enlistments of white soldiers, the President reconsidered his position.

By the end of the war, more than 186,000 black men had enlisted in Lincoln’s army, some 134,000 of whom came from slave-holding states. Some were freed blacks who had made lives for themselves in the South, but many more were slaves who, when troops marched through the Confederacy, took it upon themselves to claim their freedom and sign up for the Union cause.

And as black soldiers entered the military, the relationship between the war and the institution of slavery became more intertwined. As Lincoln saw it, with the inclusion of African-Americans in the conflict, the fight had become defined by the question of slavery.

Lincoln moves towards emancipation

In early autumn, the President began to make overtures toward formal emancipation, and on January 1, 1863, he announced his Emancipation Proclamation. The declaration was largely a military gesture, pronouncing freedom for all slaves in the Confederacy – those states over which Lincoln had no control. Still, the symbolic directive had the effect of highlighting the centrality of slavery to the Union cause.

As historian Eric Foner writes, “never before had so large a number of slaves been declared free. By making the army an agent of emancipation and wedding the goals of Union and abolition, it ensured that northern victory would produce a social transformation in the South and a redefinition of the place of blacks in American life.”

On a federal level, too, Lincoln’s announcement of wartime emancipation prompted members of Congress to begin looking toward steps to ensure the permanent abolition of the institution of slavery from the states.

On December 14, 1863, nearly a year after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Congressman James Ashley of Ohio introduced a bill supporting a federal prohibition on slavery. A month later, Missouri Senator John Henderson submitted a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment.

Though for many the question of slavery had become moral and ideological, it was also political, and in March 1864, in the early lead-up to the presidential election, Representatives James Wilson of Iowa and Isaac Arnold of Illinois offered a speech lauding the recent proposal and tying the measure directly to Lincoln’s re-election.

The amendment, said Arnold, would distinguish the Republicans from the southern “slave kings.” Democrats, said Wilson, were working solely “in the interests of slavery.”

The two speeches suggested that the Republican Party – Lincoln’s Party – had begun to align itself with the push for an anti-slavery amendment.

But Lincoln, himself, remained quiet on the matter, and some began to question the President’s commitment to emancipation.

In late spring, there emerged a coalition of anti-slavery agitators, forming the new Radical Democracy party. Led by John C. Fremont, the party endorsed the anti-slavery amendment and also called for passage of a provision guaranteeing civil rights more broadly.

As historian Michael Vorenberg argues, it was, in fact, the creation of Radical Democracy and its embrace of the 13th amendment that prompted Lincoln’s final turn toward abolition. Upon accepting the Republican nomination for president, Lincoln publicly endorsed constitutional emancipation for the first time.

His formal support of the amendment, as well as more general efforts by Republicans to broker compromise toward a cohesive political party, sufficiently weakened the platform of Radical Democracy, and in September, Fremont withdrew from the race.

Lincoln at center of controversy

That fall, as Lincoln defeated Democratic candidate George McClellan and secured his second presidential bid, Congress continued to debate the passage of the 13th amendment. This time, however, the President positioned himself at the center of the controversy.

Lincoln argued that emancipation would so undermine the morale of the Confederacy that it would weaken their military and bring about a swift end to the war. The President undertook his own campaign for passage of the amendment, and his political allies and cabinet members helped to further the cause, convincing constituents and state legislatures to appeal directly to their congressmen for passage of the amendment.

The proposal had passed quickly through the Senate the previous spring, but in the House of Representatives debates created divisive partisan factions, with little certainty as to the fate of the proposal. Finally, after months of conflict, on January 31, 1865, the amendment passed 119-56, a two-vote margin. In December, it was formally adopted.

The ratification of 13th amendment conferred upon Congress the power to enforce the abolition of slavery by appropriate legislation, granting the federal government the constitutional authority to dictate power relationships among individual citizens as it never had before.

As the text reads:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

But many continued to argue over the scope of that power.

Less than a year after ratification, Congress called upon the enforcement power from Section 2 to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866, granting African-Americans citizenship and equal protection. Proponents of the law argued that the 13th amendment authorized the federal government to legislate state action; critics maintained that unequal treatment was distinct from slavery such that the 1866 Act was beyond the amendment’s reach.

In response to these debates, and as a direct outgrowth of the enforcement clause, Congress went on to pass the 14th and 15th amendments in quick succession, defining citizenship and equal rights and banning voting restrictions based on race.

The 14th amendment would become the Supreme Court’s principle tool in deciding civil rights cases through the 20th century. Still the 13th amendment, while less applicable to subsequent controversies than its counterpart, served to fundamentally reshape the American landscape.

And while its eventual champion may have begun as little more than a symbolic emancipator, Lincoln’s 1865 campaign for ratification served to launch perhaps the greatest legal, economic and social revolution the United States has ever seen.

Abigail Perkiss is an assistant professor of history at Kean University in Union, New Jersey, and a fellow at the Kean University Center for History, Politics and Policy. Follow her on Twitter at @Abiperk.

For further reading:

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. W.W. Norton and Company, 2010.

Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth amendment. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Recent Historical Stories

How much do you know about the American flag?

Did Abraham Lincoln omit God from the Gettysburg Address?

10 facts about Thomas Jefferson for his 270th birthday

10 interesting birthday facts about James Madison