Ancient Mayan compartments — used to hold water — discovered in Mexico. See them

Hidden under an ancient Mayan building in Mexico, archaeologists discovered a compartment that was used to hold rainwater — or something more sinister.

At the archaeological site of Tulum, a large construction site sits atop a hill overlooking the Caribbean Sea. Centuries ago, this was a bustling city first occupied around 1200 A.D., according to an April 29 news release from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Along an outer wall of the city, archaeologists had discovered two chultúns outside, a type of bottle-shaped compartment that was used to hold rainwater, officials said.

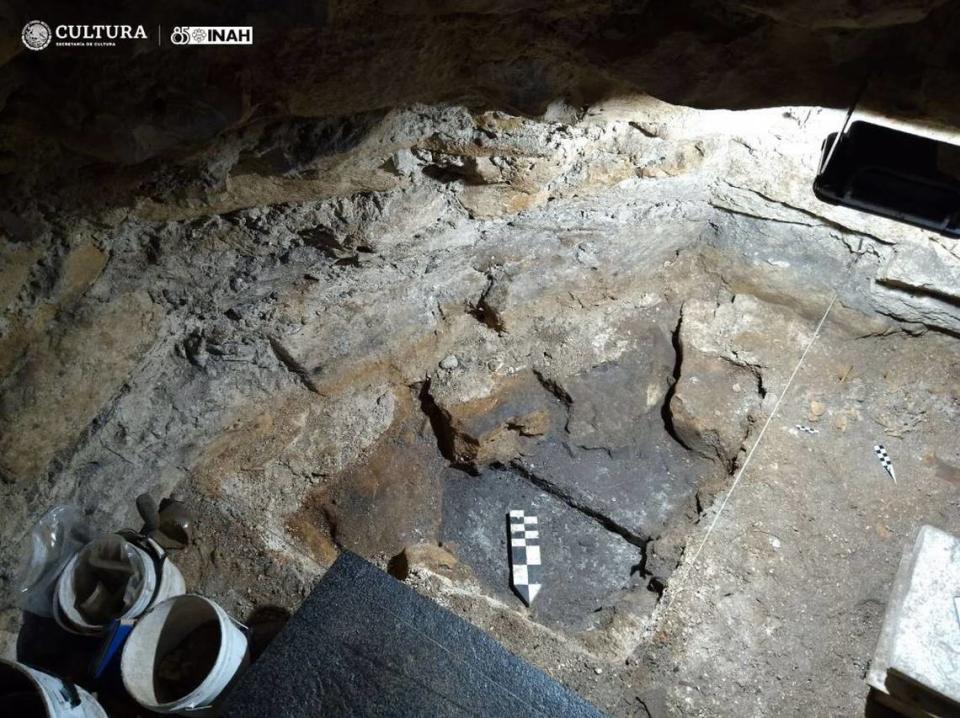

The compartments are built into the ground, with a small hole at the entrance opening up to a small cavern below.

This style of water storage was commonly used by the Mayan people, but they have been found exclusively outside of buildings.

Until now.

When archaeologists worked to excavate Building 25 at the Tulum site, a stone was removed from the floor of the building to reveal an opening, according to officials.

Uncover more archaeological finds

What are we learning about the past? Here are three of our most eye-catching archaeology stories from the past week.

→ Massive 2,200-year-old tomb with grand interior unearthed in China

→1,000-year-old weapon — the first of its kind — found sticking out of grave in Spain

→ Workers unearth steelworks at medieval castle in UK — and find someone's 'hidey-hole'

Just 21 inches long and 18 inches wide, the opening was the top of a chultún. This is the first chultún that has been discovered inside a Mayan construction, officials said.

That wasn’t the only thing that made this compartment unique.

The compartment also appeared to have never held water, researchers said.

The archaeologists said the chultún was built from layers of ground coral, less than an inch thick, which formed the surface of the cavern and sat on top of reddish clay. There were also medium-sized stones and thick layers of pure ash.

The researchers believe instead of water, this chultún may have been used to store food and plants.

Then, as the researchers reached the deepest section of the chultún, they found human remains and burned stones.

There were layers of ash, which told the archaeologists that there had been repeated combustion down in the chultún, but there was no evidence of fire or soot on the walls, suggesting the rest of the compartment was built up around the pit later.

The researchers suggest that the chultún originally had a ritualistic purpose, as multiple sets of human remains were discovered.

They also believe the site may have been looted at some point in history during the pre-Hispanic or colonial era because of a few of the items found inside.

The team will continue to analyze the human remains and sediment found in the chultún to determine what may have been stored inside.

The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia posted a video tour of the site on YouTube.

The archaeological site is located in Quintana Roo, on the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

Google Translate was used to translate the news release from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

‘Mysterious’ purple lump found at ancient Roman ruins was once ‘worth more than gold’

Ancient shells — found in American West — may have been used as trumpets, study says

Package from mystery sender arrives at Poland museum — with missing artifacts inside

Workers cleaning up dirt at 800-year-old temple uncover dozens of ancient statues