Ancient shells — found in American West — may have been used as trumpets, study says

If you were standing on the edge of a canyon in the San Juan Basin of the Colorado Plateau about 1,200 years ago, you may have heard a loud, distant sound reverberating off the rock faces and ricocheting across the desert.

Like the gong of a bell or the deep tone of a ship’s horn, the sound would be a rich single note cutting through the dry air.

This bellow would have been a regular occurrence for the indigenous Pueblo people of the modern-day American Southwest, but it wouldn’t come from the musical instruments we know today.

Instead, the booming noise came with help from the ocean — a conch shell.

In a new study, published May 2 in the journal Antiquity, researchers examine how sound traveled across the desert landscape and how conch shells may have been used as a way to bring communities together.

Chaco Canyon, in modern-day New Mexico, was home to many indigenous people over the millennia, according to the study, including the ancient Pueblo who occupied the region between 850 and 1150 A.D. and left behind massive constructions.

“Twelve massive, sandstone masonry canyon great houses, including Pueblo Bonito, are some of the best-preserved pre-Hispanic buildings in the southwest, with standing walls up to (26 feet) high,” the researchers wrote. “About 200 additional great houses dot the ‘greater Chaco landscape’ beyond Chaco Canyon over an area covering approximately 60,000 square miles.”

The great houses, much larger constructions than personal residences, are central to communities, according to the study, and occupy a geographically center location surrounded by smaller “domestic habitation sites.”

This was important for communication between the great houses, the researchers said, and for establishing a sense of connection between the buildings from miles away.

But while archaeologists might be interested in the landscapes of the American Southwest, the study focused on something different — the soundscapes.

“A soundscape is defined as the ‘acoustic environment as perceived or experienced and/or understood by a person or people, in context,’” according to the study. “In the Chacoan world, sounds created by human voices, animals, water, wind thunderstorms, daily activities and musical instruments would have comprised the ‘acoustic environment.’”

This includes trumpets made from conch shells, discovered buried with human remains despite originating from the Pacific Ocean about 600 miles to the southwest, the researchers said.

“By removing the pointed end of the shell and blowing through the whorls, it is possible to create a very loud blast,” according to the study.

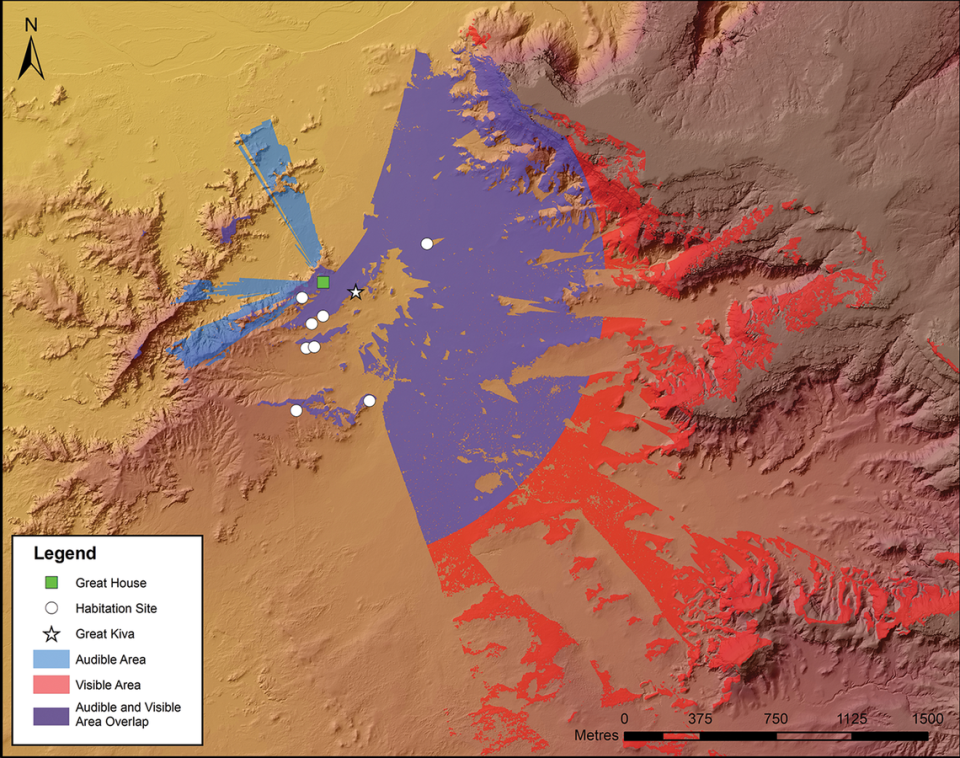

The researchers chose a central location in the Chaco Culture National Historical Park and used a computer model to replicate the volume and decibel of an ancient conch trumpet. Then, the researchers used geographic mapping to see how far the sound would have traveled across the landscape to surrounding communities likely to have interacted with one another, according to the study.

“Our results indicate that on a quiet morning, the conch could be heard over ambient background sounds for a distance of up to approximately 1,418 meters,” the researchers said, about a mile in any given direction.

Multiple habitation sites around the great house were in this range, suggesting the smaller towns were constructed intentionally so they could hear the conch shell from the great house, according to the study.

The sound of the conch may have been used for ritualistic purposes, as seen in Pueblo and other indigenous communities today, the researchers said, or it could have simply been a way to get attention quickly.

“If leaders atop great houses needed to quickly communicate with all community residents, a conch-shell blast would have been a more effective method than relying on community residents to look in the right direction at the right time to see, for example, smoke/mirror signals,” the researchers said. “Our research suggests that, like the reach of the sound of a church bell in medieval times, the sound of a conch-shell trumpet may have been one element binding Chacoan communities together.”

Package from mystery sender arrives at Poland museum — with missing artifacts inside

A bad omen may have caused this ship to sink 115 years ago. It’s found decades later

Workers unearth steelworks at medieval castle in UK — and find someone’s ‘hidey-hole’

Ancient walls — that served as ‘Google Maps’ for the Mayans — discovered in Mexico