B-B-B-Bernie and the Jets

As Bernie Sanders surges in Iowa and New Hampshire polls, many Americans are hearing the presidential candidate rage against “the billionaire class” for the first time. What they don’t know is what his fellow Vermonters know: The 74-year-old socialist seeking the Democratic nomination operates less like a rabble-rouser at home and more like most other U.S. senators: delivering services for veterans, Medicare for the elderly and defense spending for their state.

Vermont is tiny (pop. 620,000), overwhelmingly rural and white and heavily populated with migrants—including Sanders—who moved there from New York many years ago. On the back roads of the Northeast Kingdom, the most rural part of the state, aging hippies and their heirs still share tiny towns with fifth-generation loggers and dairy farmers. An unpaved road leads into Stannard (pop. 140), 45 minutes from the Canadian border, the town where Bernie arrived in the mid-1960s, after a childhood in Brooklyn, college in Chicago and a stint on a kibbutz.

Related: Sanders Gets Cool Reception on Christian Campus

In Stannard, Sanders was known as a serious reader who loved to talk politics. His funky house has changed ownership, but the community—named after a Union Army war hero—remains an outpost of ’60s-style idealism, including a large compost operation not far from the town hall owned and operated by a new generation of former New Yorkers. Stannard, like other towns in the state, has such a lively participatory democracy that, as Tom Gilbert, a local compost producer and farmer, puts it, “Vermonters all know their Robert’s Rules.”

Down the road, Sanders’s old neighbor Regina Troiano—like Sanders, a native New Yorker— still lives on the 175 acres she bought in 1972. When the senator swings through Stannard every year or two, Troiano hosts town meetings or fundraisers for him. The last time she saw Sanders, he pulled into her driveway in a Ford Fiesta carrying a church-hall-size coffee machine and bagels. “He’s incredibly generous,” she says. “He’s always making sure everyone gets enough—to eat.”

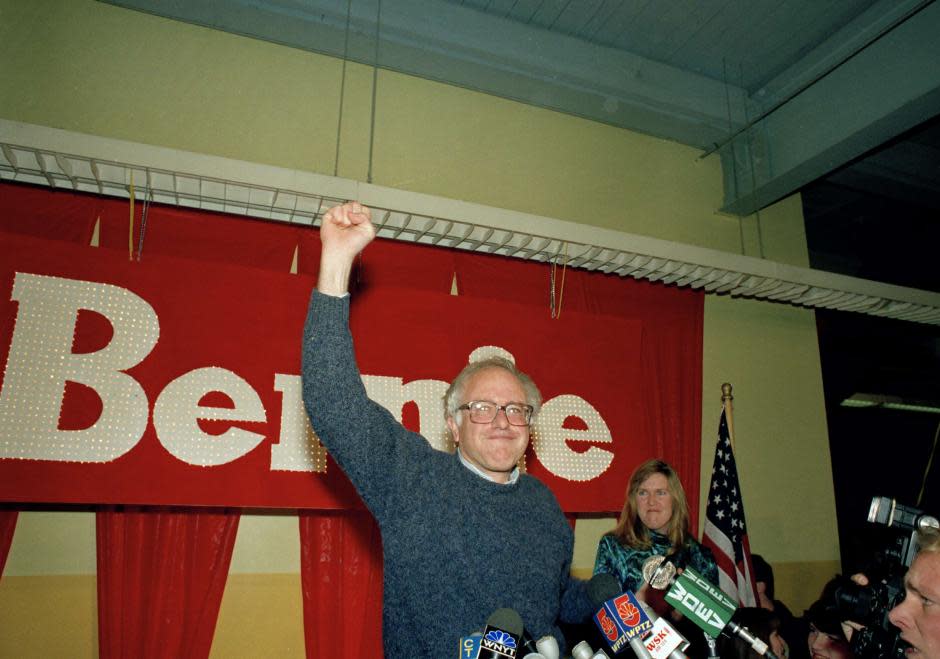

Sanders left Stannard in the late 1970s and won his first election in 1981, becoming the mayor of Burlington, the state’s largest city, with just 42,000 residents. Sanders slipped into office by just 12 votes but was re-elected four times as he gained a reputation as a pragmatist whose improvements transformed the city. Despite jokes about the People’s Republic of Burlington, Mayor Sanders created a Community and Economic Development Office that had some progressive aspirations like promoting affordable housing, but it also worked with local businesses. The mayor’s office took on a derelict industrial area near the shore of Lake Champlain. After voters rejected a bond referendum to develop the waterfront, Sanders’s office dusted off a Vermont public trust doctrine from the 19th century that allowed the city to buy the land for a fraction of the price that private developers would have had to pay. Since the bond issue had failed, the city made relatively inexpensive improvements—removing barbed wire, oil tanks and other industrial waste and transforming the railroad tracks into a paved bike path—and then invited developers back into the now beautified area. Today, it’s the well-regarded, tourist-friendly Waterfront Park.

“[The city] created all the infrastructure,” says Melinda Moulton, CEO of Main Street Landing, a redevelopment company involved with the Waterfront who hails Sanders as a politician who helped businesses in Vermont behave in socially conscious ways.

As mayor, Sanders developed other passionate business supporters, including Ben Cohen, the Ben in Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, who has been opening for the senator at presidential campaign stump speeches. Cohen no longer makes ice cream. He sold his eponymous company to British-Dutch mega-corporation Unilever in 2001—which makes it the rare corporate merger Sanders doesn’t decry. Cohen says he’d like to name an ice cream after the progressive hero—“Bernie’s Binge,” a concoction with a large chunk of rich chocolate in the center that needs to be broken up with a spoon.

Sanders ran for Congress in 1990 as an independent and won. He was an intriguing pro-business socialist, and he also got a big lift from the gun control issue, but not in the way you might think. When his moderate Republican opponent endorsed an assault weapons ban, Sanders stayed quiet. Steven Rosenfeld, who worked with Sanders on that race and wrote a book about the experience, says Sanders didn’t need to have it explained to him that “being against guns in Vermont is like being against black-and-white cows.”

Related: The Debate about Presidential Debates

Like everyone running for the Democratic presidential nomination this year, Sanders favors stricter gun control. But he tempers his stance in a way that plays well at home. In 2005, he supported a bill protecting gun sellers from lawsuits by survivors of gun violence. Asked this year whether he regrets preventing Aurora, Colorado, theater victims from suing local gun retailer Lucky Gunner, where convicted shooter James Holmes allegedly bought weapons, Sanders told CNN that nobody holds hammer distributors liable. “That is not what a lawsuit should be about,” he said, adding that “99.9 percent of gun owners obey the law.” It’s little wonder that a super PAC supporting rival Democratic presidential candidate Martin O’Malley has already run an ad declaring that “Bernie Sanders is no progressive when it comes to guns.”

Navigating divisive cultural issues like guns has been a Sanders mainstay. On the presidential campaign stump, he bellows, “I will never understand why middle-class and blue-collar Republicans continue to vote against their own interests!” The line is a guaranteed crowd-pleaser, and, in fact, Sanders, who won re-election to the U.S. Senate in 2012 with 71 percent of the vote, knows how to spur these swing voters that Democrats crave. His coalition of NPR-listening, pro-gay marriage, pro-choice progressives, along with gun-toting, maple-sugar-tapping lumberjacks, is quite a feat. Flatlanders (as the newer, liberal-minded Vermonters are commonly known) and Woodchucks (their hunting- and tradition-minded natives) had a period of open warfare in 2000, when many Woodchucks were furious about Vermont legalizing gay civil unions and restricting the clear-cutting of woodlands. But even then, pickup trucks with gun racks sported “Take Back Vermont” stickers beside “Bernie” stickers.

When Sanders ran for the Senate in 2006, Senator Patrick Leahy—the only Democrat Vermonters have ever sent there—noted Sanders’s cross-party appeal. “A lot of the lower-income parts of our state are Republican,” Leahy told The New York Times. “I saw Bernie signs all over those parts of the state.” (For more about Bernie in Vermont, the Burlington independent weekly Seven Days has compiled an online library going back decades, called BernieBeat.)

Related: Sanders Defends Immigration Stance

In Washington for almost 25 years, Sanders has operated like any other member who brings home the bacon. As chairman of the Senate Veterans Affairs' committee, Sanders has proved himself a skilled lawmaker able to cut deals across the political spectrum. He and John McCain won $500 million for the Veterans Affairs department to hire more doctors and lease medical facilities to expand VA services. Through his efforts, Vermont snagged more federally funded community health centers per capita than any other state. The VA placed the nation’s pre-eminent treatment center for post-traumatic stress disorder in White River Junction, and he obtained $135 million in federal flooding funds after 2011’s Hurricane Irene.

Vermont’s lone congressman, Democrat Peter Welch, credits Sanders for his focus on “concrete things” like getting significant funds for satellite VA clinics around the state so rural vets don’t have to drive hours to get care, and bringing in civilian community health centers that are federally funded. “He is primarily known as an advocate for the underdog,” Welch says. “He’s the guy who’s gonna be standing up and calling it out on behalf of everyday people.”

As he sipped tea and sucked on herbal throat lozenges last month while campaigning in New Hampshire, Sanders reflected on his constituent work. “You can give all the great speeches you want on the floor,” he told Newsweek, referring to the Senate floor like someone who has spent a quarter century in the Capitol. “But there are people who aren’t getting their veterans benefits, and I’ll be damned if my office is not going to do everything they can to make sure they get those benefits.”

When it comes to defense, Sanders is also politically adroit. He voted against the Iraq War, a position that, among others, makes him a hero to the left. But he isn’t averse to delivering Pentagon pork. After years of publicly attacking defense contractor Lockheed Martin for cost overruns and overpaid executives, he persuaded the defense behemoth, which manages the Sandia Labs research center for the Department of Energy, to place a Sandia satellite lab in Burlington. Even more lucrative for Vermont, Sanders snagged a piece of Lockheed’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program—a controversial $1.5 trillion program yielding the most expensive aircraft in history. Eighteen of the jets will be placed at the Burlington airport for the Vermont National Guard. Vermont progressives went ballistic, demanded that the “killing machines” be kept out of the Green Mountain State, but Sanders held his ground. At a town hall meeting, he defended the basing, saying with a politician’s shrug that the F-35s were “essentially built.”

Sanders’s money savvy hasn’t endeared him to everyone in the Northeast Kingdom. At Currier’s Quality Market in Glover, an old-time general store that is decorated with taxidermied animals (including the extinct Northeast cougar) and sells guns, hardware, groceries and homemade maple cookies, a beverage truck driver complained that Sanders was just another “lying politician” who came from out of state and had not brought any improvements to his neck of the woods. “My dad worked at GE in Rutland all his life. I’ve been on the waiting list for 10 years,” the man, who refused to give his name, says.

Related: Bernie Sanders in the House

It is true that the state has bled blue-collar jobs: The logging industry, for example, has suffered, with the number of sawmills dropping from 200 in 2005 to less than 130 now. The state lost 17,000 blue-collar jobs in the early 2000s, and while the state rebounded, the number of those jobs has not returned to pre-recession levels, as they did in neighboring New Hampshire.

Up a hill from Currier’s, there’s resistance to Bernie from the left. A northeastern hippie relic—the Bread and Puppet Theater and Museum—seems like a throwback to the Woodstock era. This spot is Bernie territory, but it also has progressives who think he’s too Washington, too mainstream. Chris Schroth, 28, a musician and carpenter, was preparing supper in the theater’s communal kitchen. He says he is skeptical of Sanders’s commitment to what he dubs “a conscious people’s movement.” He also says Sanders did not do enough to support Act 48, which would have made Vermont the first state in the union with a single-payer health system. The bill was set to become law earlier this year when Governor Peter Shumlin, a Democrat, decided it was too costly and abruptly shelved it. Schroth was among those arrested at a protest at the state Capitol against the scuttling. “Bernie was holding town halls talking about national health care, but he wasn’t lifting up the local movement,” Schroth laments.

Instead of grabbing a pitchfork and joining the fight for the state law, Sanders demurred. “Well, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, I’m kinda busy being a United States senator,” he says. “I’m not the governor of the state.”

If this kind of political pragmatism from a nontraditional candidate sounds familiar, it should. Progressives once saw Barack Obama as the Moses of “hope and change.” He also surprised pundits with huge crowds and gave Hillary Clinton ulcers. After the 2008 election, Obama’s base discovered a politician who appointed establishment mascot Larry Summers as treasury secretary, expanded drone strikes and opened the Arctic to oil drilling. Like the president who once presented himself as an audaciously new sort of politician, Sanders actually plays—and plays well—by the old rules of the game.

Related Articles