Bear bile-extracting farms near collapse in SKorea

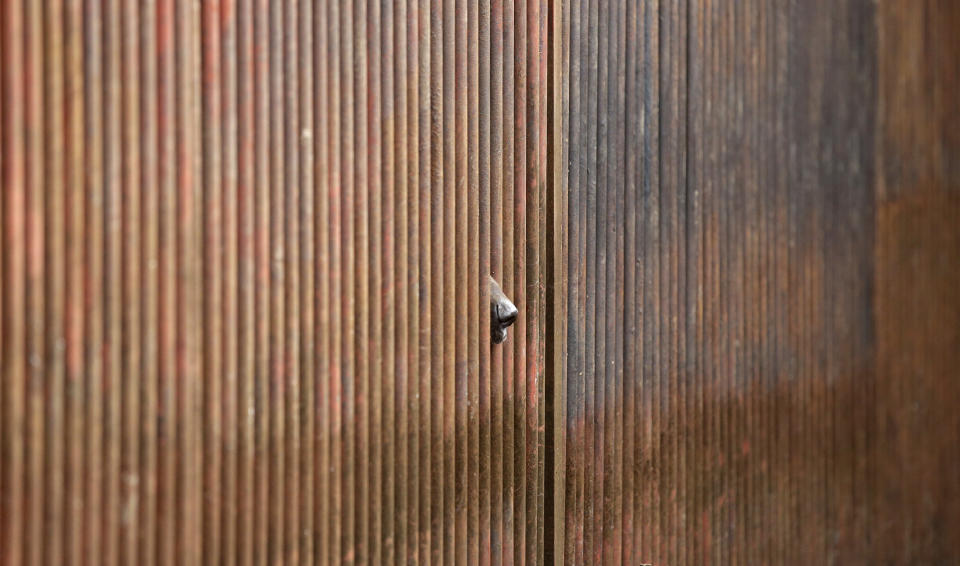

DANGJIN, South Korea (AP) — Several bears lie on top of each other, as still as teddy bears, as they gaze out past rusty iron bars. Others pace restlessly. The ground below their metal cages is littered with feces, Krispy Kreme doughnuts, dog food and fruit. They've been kept in these dirty pens since birth, bred for a single purpose: to be killed for their bile.

But these bears aren't dying. The industry is.

Though their bile has been used as medicine in Asia for thousands of years, cheaper foreign sources, growing skepticism over bear bile's medicinal value and worries about international condemnation have led to a huge drop in South Korean demand. Kim KwangSoo, the owner of this farm in Dangjin, about 120 kilometers (about 75 miles) south of Seoul, said he hasn't had a bear bile customer in five years.

That, however, doesn't ensure the animals a peaceful future. The government is offering farmers money and incentives to sterilize or slaughter their bears, but the farmers are demanding much more.

Kim, secretary general of a bear farmers' association, said farmers are considering suing or even more drastic measures — such as harming their bears — if they can't reach a deal. He said farmers raised the issue of greater government compensation Thursday during a meeting with government officials and civilian experts, and that they will meet again this month.

To highlight their grievances, farmers in November brought caged bears to downtown Seoul and near a government complex in the city of Sejong. Kim said farmers are now considering hauling bears, 20 per cage, to the Sejong government complex in the hope that the fighting, cramped animals will bring them attention.

"People talk about animal welfare ... but bear farmers aren't getting any welfare," said Yun Youngdeok, who runs a bear farm near Seoul. "We feel like we are dying earlier (than our bears)."

South Korea is one of the few countries that allow the farming of bears to extract bile for traditional medicine. About 50 farms are raising about 1,000 bears, mostly Asiatic black bears, also known as moon bears. They are the descendants of bears imported from Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries when bear farming began here in the early 1980s.

Kim said South Koreans were once willing to pay between 20 million to 30 million won ($18,450-$27,680) to have a bear slaughtered for its bile. But farmers ran into trouble about a decade ago, when bear bile from China and Vietnam became more readily available.

Now the farmers have an even bigger problem: Bear bile just isn't popular. South Korea imported only 2.8 kilograms (6.2 pounds) of dried forms of bear gall bladders between 2008 and 2012, according to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. In 2011, about 94 percent of South Koreans surveyed by the private Hangil Research Center said they had never bought bear bile and had no intention of doing so. The telephone survey of 1,000 people had a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3.1 percentage points.

The bear farmers' association says most of its members haven't sold any bile in five or six years. Meanwhile, huge debts from feeding and maintaining the bears are mounting. Kim, who has about 270 bears at his farm, said their upkeep costs him about 300 million won ($276,750) annually.

The Environment Ministry said it plans to spend about 6.2 billion won ($5.7 million) by 2016 on an anti-breeding campaign, but that no final compensation plan for farmers has been settled. Officials wouldn't elaborate but called the campaign a meaningful first step toward ending the industry.

Kim, however, said ministry officials recently proposed that farmers receive about 1.3 million won ($1,200) from the government for the sterilization of one bear; 400,000 won ($370) annually for feed cost; and 1.5 million won ($1,390) for the slaughter of bears older than 10.

Farmers say that isn't enough, and that the government should take more responsibility for their troubled businesses because officials earlier encouraged them to raise bears. The government started allowing bear imports in 1981, but Environment Ministry officials say there are no official documents showing it encouraged bear farming.

Bear bile has been used in many Asian countries to treat a range of illnesses, including abscesses, hemorrhoids, epilepsy and cysts. Until recently, many South Koreans believed bear bile could cure all diseases and bolster vitality and stamina.

"It's not a panacea," said Kim Hocheol, a Korean traditional medicine professor at Seoul's Kyung Hee University. He said there are also alternative medical ingredients that can replace bear bile, so most traditional doctors in South Korea don't suggest expensive bear parts.

In China, where bear bile harvesting is legal, more than 10,000 bears are kept in farms, their cages sometimes so small that they are unable to turn around or stand on all fours, according to Animals Asia, a Hong Kong-based animal welfare group. The organization said that about 2,400 bears are illegally raised in farms in Vietnam, which outlawed the practice in 2005.

As for the South Korean bears, their lives may improve little beyond their current state no matter how much government money farmers get. South Korea is trying to restore a sub-species of the moon bear, but farm bears don't count because they are likely mixed breeds.

So they probably will stay in places like the Dangin farm, the largest of its kind in South Korea, as long as they live.

The cages, set up just above the ground, are in varying sizes. Ten 100-kilogram (220-pound) bears share a 40-square-meter (430-square-foot) enclosure, and four 130-kilogram (290-pound) bears share 16 square meters (170 square feet).

Some bears are missing a paw, or an ear. Kim, the owner, said they were attacked by bigger bears when they were cubs. Some bears are caged by themselves because they are too violent.

Some bears spend their days repeatedly moving back and forth. It's a motion researchers say is triggered from the stress of being locked up in a small place.