Colorado theater shooting trial: With tissues and aromatherapy, special fund helps soothe victims and family members

Aid result of lessons learned after the Oklahoma City bombing

CENTENNIAL, Colo. — Many clutched tear-soaked tissues. Some closed their eyes. Others covered their faces with the palms of their hands.

Those sitting in the victims’ section of the courtroom coped in different ways as they sat through the first day of testimony in the Colorado theater shooting trial. A therapist assisting the prosecution team recommended that victims try swabbing fragrances on their fingers to help soothe their emotions.

“So they provided scented hand lotions,” said Sandy Phillips, whose 24-year-old daughter, Jessica Ghawi, was killed by the accused gunman, James Holmes.

“We can put the scents on our fingers and breathe in when we start to feel overwhelmed in [the] courtroom.”

Phillips appreciates the lotion, but is sticking to her own scent remedy.

“I put my daughter's perfume on my index finger,” she said, her voice cracking. “It’s my reminder of why I’m here and why I have to be here.”

Holmes, once a promising neuroscience graduate student, is charged with killing 12 people and injuring 70 others at an Aurora movie house in July 2012. Holmes admits he opened fire in the theater, but has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.

Beyond the deceased or wounded, it’s estimated that more than 1,300 people either witnessed the events or were directly impacted by the tragedy.

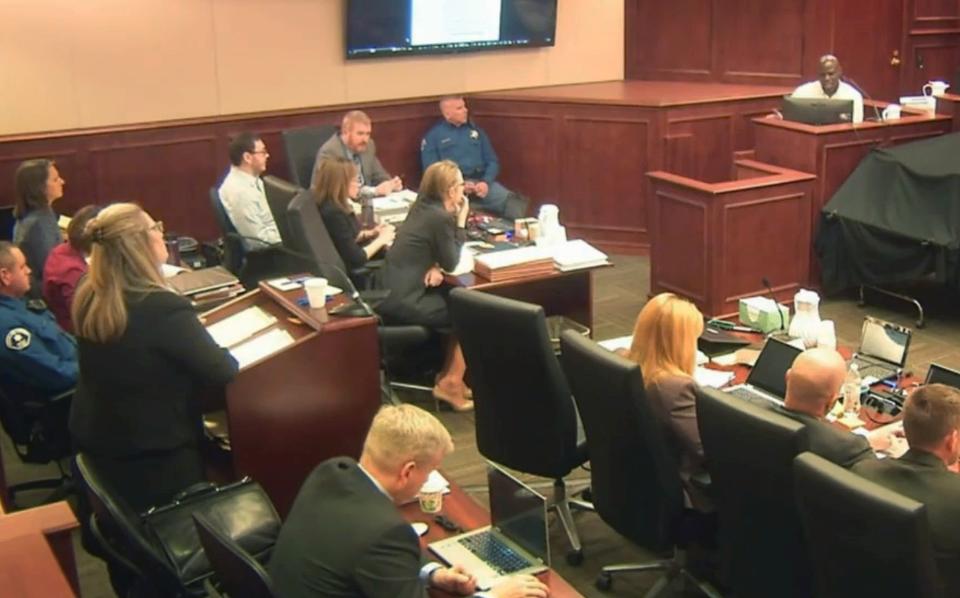

Nearly half of the 100 seats in main courtroom are dedicated to victims, their families and their friends. Bob and Arlene Holmes, the accused gunman’s parents, sit with 40 reporters across the aisle.

Emotions were raw Tuesday morning as Katie Medley, the prosecution’s first witness, recalled the blood pouring from her husband’s face at the theater and thinking that he was dead.

“We thought the shooter was going to go row by row and kill us all,” said Medley, who was nine months pregnant at the time.

Witness after witness took the stand Tuesday to describe their hell and heartache, making it clear that prosecutors plan to emphasize every life Holmes ended or ruined — and that tissues will be likely in high demand.

Supply shouldn’t be a problem.

Not long after the attack, the Arapahoe County District Attorney’s Office sought a victim assistance grant and earmarked $942 for 600 boxes of tissues to be purchased over three years. As many as 15 pastel-colored boxes of Puffs could be seen beneath the victims' chairs in the main courtroom on Tuesday. Additional seating is available in two overflow rooms and a victims’ waiting area.

The grant providing the tissues is among a legacy of triumphs for victims' rights in the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing. Congress amended the Victims of Crime Act in 2004 to better assist survivors and witnesses through the criminal justice process. An emergency reserve with $50 million is set aside annually to help communities responding to terrorist attacks and mass violence. The money is collected from federal criminal fines, forfeitures and fees collected in U.S. courts and prisons, and pays for everything from travel to therapy.

But there wasn’t a tissue budget when Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was tried in Denver 18 years ago this week.

“Those first couple of weeks, I remember us going into the bathroom and pulling out rolls of toilet paper,” recalls victims' advocate Krista Flannigan. “We eventually did a call-out for Kleenex donations. It's emotional, so that’s a necessity.”

The bombing — at the time an unprecedented terrorist attack on U.S. soil — killed 168 people and wounded nearly 700 others.

Because no protocols for a mass fatality trial existed, Flannigan and others scrambled to develop plans for transportation, a closed-circuit broadcast of the proceedings, counseling, security, funding and other unique needs.

Their model has been adapted for other mass casualty trials through the years, including the Colorado theater shooting case which began at the Arapahoe County Justice Center here this week.

“They've taken extremely good care of us, every one of them,” said Phillips, whose daughter was an aspiring sports journalist. “They’ve been helpful in lots of little ways.”

For money related to the Holmes case, the Arapahoe County District Attorney's Office was awarded $1,576,360, the 18th Judicial District Court received $216,914, and the Arapahoe County Sheriff’s Office was awarded $139,542. Any money not used will be returned to the federal emergency fund.

Yahoo News reported in February that the theater trial had already cost at least $5.5 million in public monies, most of which went to pay lawyer salaries and security expenditures, records revealed.

Through March, the district attorney had spent $758,903 of its federal money, with 90 percent going to salaries and benefits. Four full-time staffers were brought on board, including two victims’ advocates and an attorney.

That prosecutor, Lisa Teesch-Maguire, will play a key role if Holmes is to be found guilty and sentenced to death. She led off the state’s case on Tuesday by gingerly walking witnesses through their horror at the theater.

“I told him that I would take care of our baby if he didn’t make it,” Medley told Teesch-Maguire from the witness stand.

During recesses, Teesch-Maguire could be seen checking on victims in the courtroom gallery, stopping at times to provide a comforting pat on the back.

Colorado law requires that victims — among others — be consulted about case developments, assisted in preparing to testify, and afforded the opportunity to attend all hearings if desired.

“It could be 3 o’clock in the morning, and if I have a question, I’m supposed to call,” Phillips told Yahoo News.

Beyond the salaries and operating costs are the smaller touches that Flannigan said can save a day.

“Because it’s going to stir up a lot of emotions,” said Flannigan, now director of the Institute for Crime Victim Research and Policy at Florida State University. “Kleenex, water, food, and just information is critical.”

Nearly $5,000 was set aside to buy 5,000 bottles of water for victims, starting with initial hearings in 2012 and continuing through the end the trial. In the court’s grant budget is $42,100 for anyone needing child care to be at a hearing. Nearly $140,000 awarded to the sheriff’s department is being used to pay deputies to walk victims to their cars and other areas of the courthouse.

An estimated 75 victims, including Phillips and her husband, live outside of Colorado. Each is receiving 10 days of hotel, transportation, and per-diem expenses for the trial, and three days if there is a sentencing phase.

“Any little bit helps,” said Phillips, who will stay with her husband in their RV for the remainder of the five-month trial once their hotel days run out next month.

Each morning before court and throughout the day, the district attorneys' advocates meet privately with the Aurora victims who may have questions and to give them an idea of what’s ahead.

The gatherings follow the blueprint born from the Oklahoma City trial.

“It turns into an emotional debriefing because maybe there was something said or done that was particularly upsetting,” Flannigan said. “And it might not even be the trial itself; it could just be something that happens in the courtroom.”

Jason Sickles is a reporter for Yahoo News. Follow him on Twitter (@jasonsickles).