The Cutline

The CutlineScandalous tales of working for Rupert Murdoch, Rebekah Brooks bubble to surface

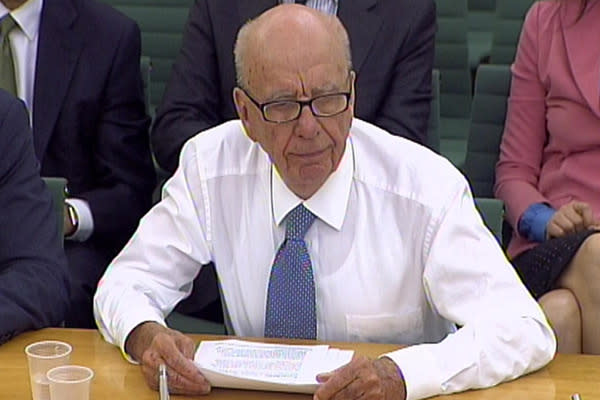

When Rupert Murdoch was asked by the select Parliament committee about his relationships with editors at News Corp.-owned newspapers, he said that other than daily calls with the editor of the Wall Street Journal, the chairman and chief executive is not involved in day-to-day editorial operations.

While that may be true now, it wasn't alway the cases, according to former staffers at his newspapers who recall a hands-on press baron whose opinion got extended hearings in story meetings, debates over front-page coverage and critical editorial decisions, even when he wasn't present.

And while News Corp. veterans say Murdoch would not have specifically ordered his editors to hack phones, the top-down pressure to break scandalous stories was so pervasive, any senior company executive who might have greenlighted such actions would have readily justified in on the grounds that it could produce a big news break.

"The culture that exists at his newspapers is a culture he has developed," Bruce Guthrie, a former editor at Murdoch's Herald Sun in Melbourne, told Reuters. "It's in some ways an amoral culture. Essentially Rupert is this hard-driving proprietor who pushes all his editors for more sales, bigger stories, he wants bigger splashes and he puts his editors under enormous pressure to deliver on that."

"When I was last at News I was astonished how some editors would almost factor in Rupert even though he was 12,000 miles away," Guthrie said. "You could almost see them thinking, 'what will Rupert think of this?'"

More from Reuters:

Toward the end of a typical week, says a former senior News International figure, the owner would routinely ring the paper's editor and grill them about the stories being worked on. One person who was present at one of these sessions said Murdoch would ask his editor to run through the list of stories reporters were chasing. He would then critique them one by one. Eventually Murdoch would hear a story he liked and make his interest apparent. That story would then become a main candidate for the front page.

News International would not comment to the news service—which, it should be noted, competes with News Corp.-owned Dow Jones Newswires—on Murdoch's level of involvement in his newspapers. Dow Jones & Company, which owns the Wall Street Journal, declined to comment. Parent company News Corporation also would not comment.

Guardian columnist Roy Greenslade, who served as a senior editor at Murdoch's Sun tabloid and Sunday Times, told Reuters that Murdoch "was known for literally dictating what tabloid editors would put in their papers."

Former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil told a House of Lords committee in 2008 that, as an editor at one of Murdoch's newspapers, "You did not have a freehold, you had a leasehold ... and that leasehold depended on accommodating his views." (Neil said Murdoch would regularly send him clippings of editorials from the Wall Street Journal, to reinforce the slant the paper should take on certain issues.)

"Rupert comes across as quite unassuming," an unnamed ex-New of the World reporter said. "'The quiet assassin,' we used to call him. He used to turn up unannounced—you wouldn't know he was there. No jacket, sleeves rolled up, at the back bench, quite hands-on." Another told Reuters: "If the Murdochs were in town, there'd be massive pressure to get some sensational story that weekend."

That pressure from Murdoch, according to other staffers, trickled down through his protégée Rebekah Brooks, the former News of the World editor and News International chief who was arrested on Sunday after resigning last week.

According to Michael Taggart, who worked for Brooks at the Sun in 2003, her tenure was marked by "ruthlessness and misogyny."

A spokesperson for Brooks would not comment on specific allegations, but told the news service the bulk of them are "ridiculous."

"The reporters who were prepared to subject themselves and others to the most ridicule," Taggart told the Associated Press, "were the ones earmarked for success."

That doesn't appear to be rhetorical exaggeration, based on some anecdotes that UK News Corp. vets are now telling about their old workplaces. Consider this tale, via the AP:

At Rupert Murdoch's tabloids, refusing to play ball meant being pushed to the sidelines. One reporter who said he went through that was Charles Begley, News of the World's Harry Potter correspondent in 2001 when Brooks was its editor.

The then 29-year-old reporter said he wore a Harry Potter costume to work and officially changed his name to that of the fictional boy wizard, all part of the paper's attempt to tap into the Pottermania sweeping both sides of the Atlantic.

On Sept. 11, hours after the fall of the Twin Towers, Begley was stunned to be chewed out by News of the World management for not wearing his costume. He said he was then ordered to attend the next news meeting in full Potter regalia.

Shaken by the demand, Begley never showed up, and soon afterward parted ways with the paper.

"I work a 10 or 12 hour day," Murdoch said at Tuesday's committee hearing. "News of the World, perhaps I lost sight of."