The Cutline

The CutlineSocial media plays role in Egypt some expected in Iran

As Egyptians celebrated in the streets of Cairo Friday, CNN's Wolf Blitzer posed a question to activist Wael Ghonim: "First Tunisia, now Egypt, what's next? "

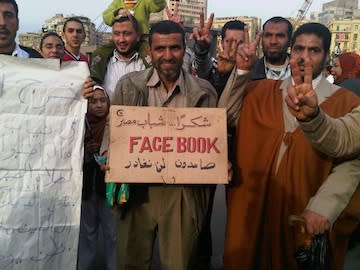

Ghonim, a 30-year-old Google executive who became a symbol of the country's democratic uprising against Hosni Mubarak's authoritarian regime, replied with two words: "Ask Facebook."

"I want to meet [Facebook founder] Mark Zuckerberg one day and thank him, actually," Ghonim said.

Dictators are toppled by people, not by media platforms. But Egyptian activists, especially the young, clearly harnessed the power and potential of social media, leading to the mass mobilizations in Tahrir Square and throughout Egypt. The Mubarak regime recognized early on that social media could loosen its grip on power. The government began disrupting Facebook and Twitter as protesters hit the streets on Jan. 25 before shutting down the Internet two days later.

In addition to organizing, Egyptian activists used Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter to share information and videos. Many of these digital offerings made the rounds online but were later amplified by Al Jazeera and news outlets around the world. "This revolution started online," Ghonim told Blitzer. "This revolution started on Facebook."

Egypt's uprising followed on the heels of Tunisia's. In each case, protestors employed social media to help oust an authoritarian government--a role some Western commentators expected Twitter to play in Iran during the election protests of 2009.

But there was no revolution in Iran, as President Ahmadinejad cracked down brutally on protesters. While "Twitter Revolution" might have made for snappy headlines, social media alone wasn't enought to topple a strongman. For a social media to work, it still needed a deliberate mobilization of activists on the ground.

So the "Twitter Revolution" talk proved premature and led to some backlash.

Evgeny Morozov writes in his new book, "The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom," that only a small minority of Iranians were actually Twitter users. Presumably, many tweeting about revolution were doing so far from the streets of Tehran.

"Iran's Twitter Revolution revealed the intense Western longing for a world where information technology is the liberator rather than the oppressor," Morozov wrote, according to a recent Slate review. In his book, Morozov writes how authoritarian regimes can use the Internet and social media to oppress people rather than such platforms only working the other way around

The New Yorker's Malcolm Gladwell, in a much-talked-about piece in October, wrote how the "revolution will not be tweeted."

It's true that tweeting alone--especially from safe environs in the West--will not cause a revolution in the Middle East. But as Egypt and Tunisia have proven, social media tools can play a significant role as as activists battle authoritarian regimes, particularly given the tight control dictators typically wield over the official media. Tomorrow's revolution, as Ghonim would likely attest, may be taking shape on Facebook today.

(Photo of Egyptians in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt on Feb. 11, 2011: AP/Tara Todras-Whitehill. Photo taken by NBC correspondent Richard Engel and uploaded via Twitter)