The Lookout

The LookoutFor jobs market, the incredible shrinking middle

Editor's Note:This is the latest in series of posts at The Lookout (and its predecessor, The Upshot), delving into how the Great Recession and the ongoing economic slump are playing out for ordinary Americans. An earlier post looked at the suburbanization of poverty.

In the era of the Great Recession, America's job market is increasingly an all-or-nothing affair.

Jobs that pay well and require highly skilled workers are continuing to increase. So are low-wage, low-skill jobs. But thanks in part to offshoring and the impact of technology, experts say, "middle-tier" jobs are on the wane.

Alan Berube, an expert on low-wage workers at the Brookings Institution think tank, calls the trend a "hollowing out of the middle." It's a long-term process, stretching over decades, Berube and other observers say -- but it's being made worse by the economic slump.

Even while the U.S. economy was producing jobs at a decent clip earlier in the last decade, many of those jobs were low-paying -- a problem that has persisted since the recession began in late 2007. And a report released this year by the progressive Center for American Progress and the Brookings Institution's Hamilton Project offers a clue to why.

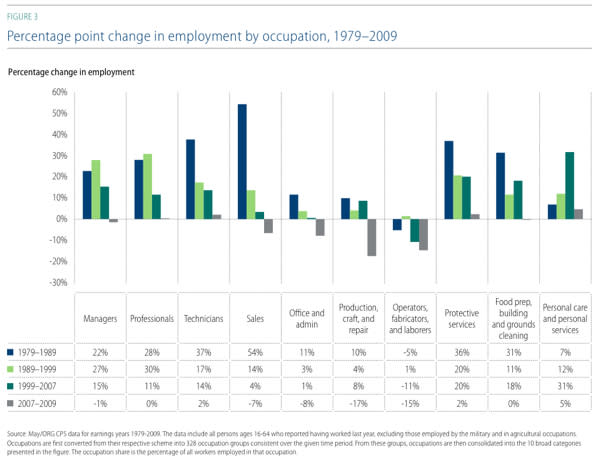

The study, called "The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market," found that "the structure of job opportunities in the United States has sharply polarized." Middle-skill jobs -- both white-collar positions involving work such as sales or clerical responsibilities, and blue-collar posts involving craft and production work -- have steadily eroded, disproportionately hurting workers without a college degree, especially males, the study found.

The trend has been underway since the 1980s. But David Autor, the MIT economics professor who conducted the study, told The Lookout that losses have sharpened in the current downturn. "The recession has exacerbated that phenomenon," he said.

That view is borne out by sobering job figures. From 2007 to 2009, the years of the recession that followed the bursting of the housing bubble, absolute numbers for all four of the middle-tier job categories measured -- sales; office and administration; production, craft and repair; and operators, fabricators and laborers -- declined significantly. During that same period, almost every category of upper-tier and lower-tier jobs increased slightly in absolute numbers, despite the downturn. In 2007, the middle-tier jobs accounted for 48.6 percent of all U.S. jobs. By 2009, their share had declined to 45.7 percent.

The vanishing middle would perhaps be less cause for concern if workers who previously did middle-tier jobs were moving into upper- and lower-tier ones in equal numbers. But the report also found that these workers appear more likely to be pushed down into the lower tier than to be lifted up to the higher tier. More often than not, midlevel workers are morphing into low-level workers, it seems.

What's at the root of the decline in these middle-tier jobs? According to the report, the core tasks of many of these jobs "follow precise, well-understood procedures." That means that as computer and communications systems have grown more efficient and widely used, these job functions can more easily be codified in computer software and performed by a machine. Alternatively, big employers can send these positions overseas, where workers do the same work at a fraction of the wages paid in the United States. Middle-tier jobs have borne the brunt of the automation and offshoring trend.

One result of the shift: The value of a college degree is greater than ever. In 1980, the hourly wage of college grads was around 1.5 times that of non-college grads. By last year, the figure was 1.95.

Indeed, another recent study, this one conducted by Berube of Brookings, found that despite the media's focus on white-collar, college-educated victims of the downturn, people with no college degree have been hit hardest. As Berube's study notes, this trend has held across the last several major economic downturns.

But in reviewing Autor's research, Berube suggested the most recent round of job losses have tracked the same hollow-middle trend that analysts are noting in the wider productive economy. In other words, compared with past downturns, this one may be particularly hurting those in the middle of the educational attainment scale -- those who have a high school diploma or even some college, but no college degree -- though, he cautions, researchers still need firmer data to confirm the trend fully.

Autor's study recommends an array of education reforms to help reverse the drift into job polarization: investments in research and development, boosting access to college and improving K-12 instruction. But for now, the findings offer further evidence that, for American workers, the gap between the haves and the have-nots is as wide as ever.

(Photo: AP/Bob Daugherty)