Obama’s Government Reform Plan Is Missing One Thing

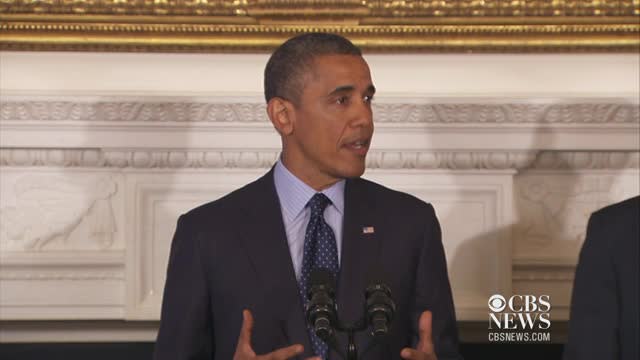

President Obama, like most of his modern predecessors, has announced a new plan to modernize the federal bureaucracy and “bring a government built for the 20th century into the 21st century.” It’s a reasonable idea meant to use digital technology to speed disaster response, kill expensive, outdated systems and make many federal agencies more responsive. But it’s unlikely to change government much because it lacks one important element: downsizing.

Many working Americans have been through the ordeal of downsizing, which has become almost a corporate rite of initiation. It can be a grueling experience, but trimming bloat, cutting costs and revising your business plan if necessary is what keeps U.S. companies healthy and profitable. The U.S. government is nothing like an ordinary company, yet political leaders like to pretend it is.

The federal workforce actually grew slightly during the recent recession. Total government employment, meanwhile, has shrunk: State and local governments have shed more than half a million jobs since the recession began. The private sector job tally is still about 1.6 million below the pre-recession level.

Most successful companies grow for a while, then stabilize at a certain size. (New job creation mostly comes from smaller firms that grow quickly.) It’s not the size of a company’s payroll that determines whether it’s successful: It’s the company’s productivity, or the amount of profit it’s able to earn for each worker. As long as productivity is improving and the return on workers is going up, a company and its employees are usually in pretty good shape.

When trouble starts

The trouble starts when companies get too big and the return on workers starts to decline. That was the general problem at IBM (IBM) in the early 1990s, when Big Blue found itself relying on outdated technology and workers with the wrong skills. To fix the tech goliath, CEO Lew Gerstner slashed poorly performing divisions and laid off thousands. IBM has since become one of the most durable profit machines in the world, but it took wrenching change to make it happen.

Downsizing has been the norm throughout corporate America during the past few years. General Motors shrank from eight automotive divisions to four as part of its 2009 bankruptcy reorganization, which allowed the wounded giant to become profitable again. Citigroup (C) has cut its staff by about 25% since 2008 in order to rein in unwieldy, if not unmanageable, operations across the globe. General Electric’s (GE) workforce has shrunk slightly since 2000, while its net income has increased; it earns about $5,200 more per employee than it did back then.

The government doesn’t exist to make a profit, so it’s hard to measure whether bureaucratic efficiency is improving. But if you measure effectiveness by how many employees it takes to generate the government's tax receipts — the equivalent of revenue — it’s not a story that would please shareholders. In 2000, adjusted for inflation, Washington took in about $1.45 million in revenue for every federal employee. Revenue per employee fell to $1.06 million during the recession and is now back to $1.24 million. In general, there were big gains in the amount of federal revenue per employee in the ‘90s, a trend that has now turned around.

Meanwhile, there are 21 Cabinet-level agencies in the federal government, and while new ones such as the Dept of Homeland Security have been created, it’s extremely difficult to eliminate government departments. Congress, which funds the government, must typically approve the elimination of the agencies it oversees. And members of Congress, as combative as they can be, typically want to protect the agencies they oversee, since that’s how they derive political power (and campaign contributions). Besides, no modern president has shown a willingness to spend his entire term — or two terms — fighting to slash the size of government and battling all the entrenched interests that are served by a status quo that rewards those with the right federal connections.

What to cut, what to keep

If a president were to attempt a thorough overhaul of the government’s business model, he might start by asking whether agencies such as the Dept. of Agriculture — established in 1862, when half of Americans worked on farms — still serve the intended purpose today. He might ask whether it’s possible to consolidate agencies such as the Dept. of Commerce, the Dept. of Labor, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and the Small Business Administration. He might ask whether there’s much overlap between the Dept. of Energy and the Department of Transportation. He might even call Rick Perry to see if he remembers that third agency he’d cut if ever elected president (the Interior Dept.).

To be fair to Obama, the last big expansion of government occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, when departments such as Energy, Housing and Urban Development and the Environmental Protection Agency were born. Presidents since then have mainly tried to reform the government at the margins, if at all. It might be nice to hear a president say the government ought to endure the same tough medicine many companies and their workers have taken as they’ve figured out how to adapt to changing times. Then again, one of the perks of being president is you don’t really have to be a CEO.

Rick Newman’s latest book is Rebounders: How Winners Pivot From Setback To Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman.