The Ticket

The TicketThe health care debate: popularity, probability, and facts

Late last week, the Kaiser Family Foundation released a poll showing that Americans have little confidence in the landmark health care reform that President Obama signed into law last year. The Kaiser survey found that just 18 percent of respondents believed that the Affordable Care Act would improve their circumstances; 31 percent said they'd be worse off, while 44 replied that the Act wouldn't make much of a difference in their lives.

With these findings in view, it's certainly no shock that the Kaiser poll also discovered that a majority of Americans--51 percent--take an unfavorable view of the 2010 health-care overhaul, compared to just 34 percent who viewed the measure favorably. These numbers marked a new low in public support for the law, so the Kaiser survey garnered a great deal of media attention.

Political leaders and lawmakers of course do well to heed such trends, since the public's views shape both their own immediate career prospects and the likely course of modification to laws such as the Affordable Care Act. But our political process can also benefit greatly from heeding the findings of prediction markets in such cases. These markets can help our political class handicap the probability of certain outcomes. (Of course, whether such outcomes match up in any way with either the public's will--or with the will of the majority of the public--is a separate question, which need not detain us here.)

One key prediction market, Intrade, currently forecasts a 37 percent likelihood that the U.S. Supreme Court will rule the health care law's controversial individual mandate is unconstitutional by the end of 2012. Under the individual mandate, all U.S. citizens are required to have health insurance; the idea behind it is to keep insurance costs down by eliminating what's known as adverse selection in the market for healthcare.

However, another future outcome that will affect the future course of the health care debate is actually a piece of the policy aims of the Affordable Care Act: whether the comparative success of the measure in providing coverage to Americans will create a significant constituency to preserve its main provisions. This, after all, is the main source of the popularity of other federal entitlements, such as Social Security and Medicare: They have both garnered enormous support in Washington by creating a sufficiently large public that is pleased with the benefits each program supplies. So in the case of the health care law, too, the question of its material value to most Americans--as opposed to the question of whether Americans think they will or will not benefit from it--will likely be the major source of its ongoing political traction, or lack thereof.

Last December, the Urban Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation published a study demonstrating that the law will significantly increase access to healthcare for many Americans. Some 27.8 million Americans who are presently uninsured will become insured under the new law, the study found. Another study by the same two nonprofits confirms reports by the Congressional Budget Office and the Rand Corporation finding it unlikely that employers will stop providing coverage to people currently with health insurance due to the law.

Other studies have disputed these findings, including one from Cornell University Human Ecology Prof. Richard Burkhauser. The conservative American Enterprise Institute has highlighted Burkauser's findings. However, in contrast to the Rand, CBO and Urban Institute research, Burkhauser makes very bold assumptions about the actions of employers and employees in response to the law's impact on existing employer-provided insurance plans. Burkhauser supplies a top bar of 13 million for the number of workers who could leave employer-provided plans in favor of the healthcare exchange.

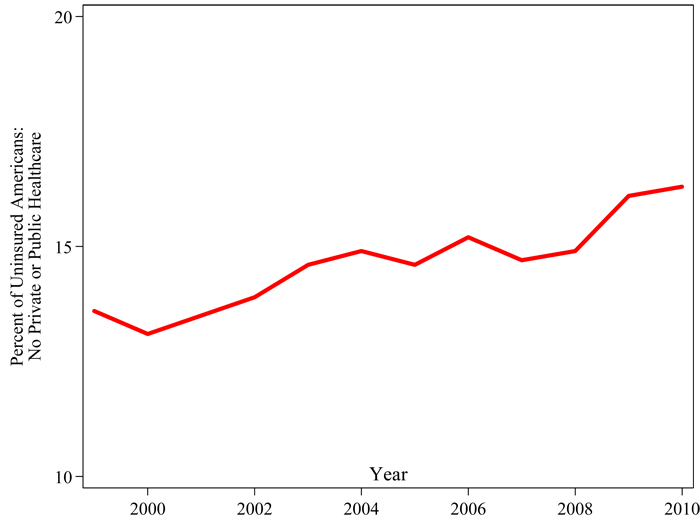

In time we will see if the new law turns this chart around. About 50,000,000 Americans were uninsured in 2010:

Data from the United Sates Census Bureau

Another practical impact of the law will be the way it alters premiums for both the present pool of insured Americans and within the federal health insurance exchanges. Once again, studies have issued conflicting findings on this question. Some conclude that that the higher rate of insurance will save the system money, by reducing the overall number of uninsured Americans and increased competition for the wider pool of insured Americans. Other studies contend that raising the volume of coverage will increase premiums for a substantial number of Americans.

The most comparable legislation, the Massachusetts health care reform signed into law by then Gov. Mitt Romney, provides some clues to how these fiercely debated policy outcome may yet unfold. The Massachusetts law clearly resulted in a reduction in uninsured people (i.e., increased access to healthcare); more than 98 percent of Massachusetts residents now have health insurance. However, the studies are mixed in their assessments of the ultimate cost of the plan. One thing is clear, however: The Massachusetts reforms are very popular. The Boston Globe reports that poll after poll show majority support for the law and that five years after it was enacted "there is no significant constituency [in Massachusetts] for repeal."

There's an important moral here, both for our key political actors, and for the public at large: What people believe about the likely impact of a given piece of legislation can be markedly different from its actual impact. It seems likely that the Affordable Care Act, if fully implemented, will end up creating benefits for a great deal more than 18 percent of Americans.

But there's also a corollary reality-based caution here: What people want to happen can also be very different from what will happen. At the present juncture, Congress and the White House have very little to say about the future implementation of the health care law; that's much more the province of the courts. These subtleties are really important if you are planning for the impact of this law on your business--or if you are thinking about campaigning or voting for or against this law.

Which leads to my next question: What do you regard as the most important factor in the health care debate? If the Signal wades into the question again, would you prefer to hear more about what the public thinks, what the likely outcomes ahead may be--or what the law itself is likely to accomplish going forward? As always, I look forward to your comments.

David Rothschild is an economist at Yahoo! Research. He has a Ph.D. in applied economics from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. His dissertation is in creating aggregated forecasts from individual-level information. Follow him on Twitter @DavMicRot and email him at PredictionBlogger@Yahoo.com.

More popular Yahoo! News stories:

• VIDEO: Rick Perry's strange stump speech in N.H.

• Herman Cain camp brands sexual harassment accusations a liberal attack

• Can Rick Perry afford to lose in Iowa?