The Ticket

The TicketThe special elections in New York and West Virginia don’t say much about Obama’s chances

Republican Scott Brown's upset victory in Massachusetts in January 2010 to replace the Senate's liberal lion Ted Kennedy turned out to be a preview of things to come, when the GOP swept into a majority in the House of Representatives and gained significant ground in the Senate in the wake of the November midterm ballot that year. Looking back, it's natural to assume that Brown's win presaged the Republican takeover: we should have known. Nor is it a giant mental leap to extrapolate from other landmark special-election wins in this cycle to the presidential election next fall--concluding that the Republicans' first win in New York's 9th District since 1923 is an equally bad sign for Barack Obama. Or that, conversely, the Democrats' win in the West Virginia governor's race on October 4 is a positive sign for Obama.

As you rush to make such connections, you are likely heeding the lure of common sense. Common sense tries to link up every dot—to succinctly explain the cause of every effect—and it does not give up easily. But while common sense can be a marvelous guide for navigating our way through the world of the present-day, it's often a nasty trap when it comes to predicting the future.

The problem is that common sense is too powerful, as Yahoo! sociologist Duncan Watts eloquently explains in his recently published book Everything is Obvious. Common sense can explain almost any event regardless of its outcome, and it can usually do so quite convincingly. When the stock market goes up, for example, we want to know why, and we can often quickly find a compelling answer: Indeed, journalists do it every day. But had stocks gone down on the same day and nothing else had changed, we could have easily found just as satisfying an explanation. If the same past can explain two different futures, then those explanations have no predictive power--no ability to differentiate between the two futures. In short, we are better served by ignoring the voice of common sense when we try to extrapolate from today to tomorrow--or at least we should discount it heavily, against every human instinct.

The unnerving truth is that thousands of entangled factors affect major events like the upcoming election--and it's almost impossible to read too little into any one of them. The best way to inoculate against overthinking any single event, such as this week's special election in West Virginia, is to watch the reaction on prediction markets like Intrade and Betfair. There, millions of dollars ride on the event's outcome. If traders with skin in the game don't flinch, then you shouldn't either--regardless of what the pundits say.

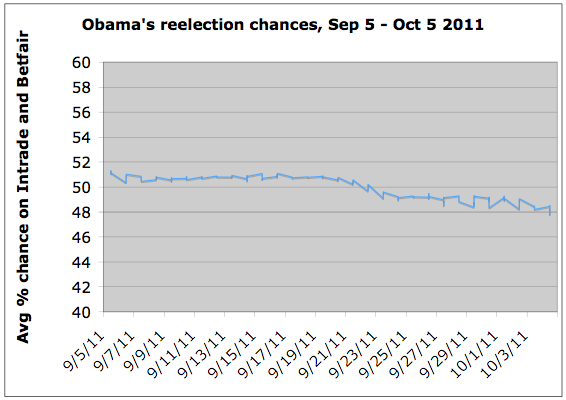

When Bob Turner won for the Republicans in New York on September 13, the prediction markets barely budged. Between September 1 and September 20, Obama's reelection chances held steady at around 49-51 percent according to Intrade, suggesting Turner's victory had little impact on the presidential race. (Obama's chances have since dipped to 47 percent in the prediction markets.) An alternate explanation is that traders already expected Turner to win, but in a separate market for the New York special election, Turner was handicapped at a 25 percent to 40 percent chance of losing in the week leading up to his election.

Likewise, when Earl Ray Tomblin, the Democrat, won the West Virginia governorship on October 4 in a race deemed too close to call just that morning, Obama's chances on the prediction markets were hardly affected.

Though pundits will expend plenty of ink and bandwidth on the implications of both the New York and West Virginia special elections, neither result actually tells us much about who will be the next president of the United States.

This reminder also summons a corollary rule: When pundits make analogies to the past to prognosticate the future, beware. They are playing on your innate reliance on common sense. Before believing them, remember how easy it is to construct plausible explanations for anything after the fact--or to cherry pick information to make predicted outcomes seem more common-sensical.

Here again, the stock market furnishes a useful cautionary example. When financial bubbles pop, every bone in our body says, "We should have known." But we needn't beat ourselves up. Millions upon millions of dollars invested by Wall Streeters and Main Streeters alike said that the bubble price was the right price. Not only is it not true that we should have known, we couldn't have known. Common sense tries to persuade us of something much stronger than "hindsight is 20/20": that, in fact, our foresight should have been 20/20. No forecaster can afford to take such sentiments to heart.

David Pennock has a Ph.D. in computer science from the University of Michigan and currently heads the algorithmic economics group at Yahoo! Research. You can follow him on twitter @pennockd.