Trending Now

Trending NowY! Big Story: The missing

Everything you need to get up to speed on the big story of the day

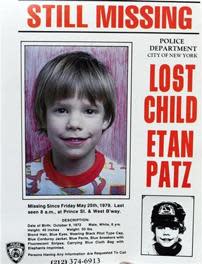

May 25 is National Missing Children's Day. Etan Patz, its poster child, remains missing.

After 33 years, a man has stepped forward to confess to strangling Patz. Proof will be another matter, as the former grocery store worker has not been able to provide the body nor has he given a motive. As for the confession's timing, a realtor who rented the suspect his apartment told the Star Ledger that maintenance people heard he was battling cancer, but nothing more has been substantiated.

When Etan vanished May 25, 1979, he was said to be the first missing child featured on a milk carton; his father Stan Patz, a professional photographer, supplied the photo. Etan's face was the first to appear on a Times Square electronic billboard six years later. In an era of highly publicized kidnappings — among them Adam Walsh, whose 1981 disappearance prompted his father to host "America's Most Wanted" — the campaign convinced President Ronald Reagan to call May 25 National Missing Children's Day. A year later, Congress set up the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

How Etan changed the nation's laws: Before this case, how law enforcement dealt with the missing varied.

Etan's disappearance revealed that the systems in place were inadequate to deal with missing children. Schools did not alert parents if children did not show up. Depending on the jurisdiction, a police response could take as long as 24 to 72 hours after a child's disappearance. According to the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), in 76% of missing cases where the child is abducted by a non-family member and killed, the murder occurs within the first three hours of the kidnapping. Furthermore, there was little communication between police departments; if a child was taken over city or state lines, the trail was often lost. (April 28, The Economist)

The wrenching horror of a missing or murdered child fueled other changes: The 1989 kidnapping of 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling led to the federal sex offender registry, although these days many know such legislation as Megan's Law, in honor of Megan Kanka, killed by her neighbor in 1994. (Wetterling remains missing.)

The 1996 murder of 9-year-old Texas girl Amber Hagerman triggered the AMBER alerts. Her case remains unsolved, but the alerts have improved clearance rates of finding children to 97% — in 1984, the odds had been 62%.

The numbers:

Stranger abductions are high-profile partly because they're extremely rare: About 110-200 are snatched, out of 600,000-800,000 children that go missing each year.

The statistic of a child murder happening within three hours of an abduction can be a panicking, but misleading one, that comes from a 1993 Washington project. Of 600 murders studied, 76% had been killed within three hours. "It suggests if we don't find them in the first 24 hours, we should give up hope," NCMEC executive director Bob Lowery tells Yahoo!, but points out that cases like Jaycee Dugard and Elizabeth Smart clearly offer hope.

What that timeline should do is instill a sense of urgency and the importance of alerting police immediately.

In nearly 60 percent of the cases studied, more than two hours passed between the time someone realized the child was missing and the time police were notified (2006 Child Abduction Study, Washington State Office of the Attorney).

In the case of California teen Sierra LaMar, the high school didn't notify the parents of her absenteeism until 11 hours later — typical procedure even in the high-tech San Francisco Bay Area. (The school has since changed that policy.)

How to protect your children and how your children can protect themselves:

In an age where stolen iPhones deliver their own locations, it's tempting to look to technology — from smart phones and GPS tracking devices to social media — as a precaution. NCMEC doesn't recommend gadgets, but Lowery says, "One key piece is a current image of the child. The FBI has an iPhone app for parents that we do endorse." The Child ID app helps parents keep current data, including a photograph. (No information is shared with the government unless parents enable permission.)

The most effective tool, Lowery says, is the spirit of the kids themselves. "Children who are more assertive and willing to bring attention, who are willing to say 'no' to an adult figure, are the ones less likely to be successfully abducted." More ways to protect minors and report abuse:

Microsoft and Yahoo! Safely give online tools on how kids can avoid predators.

NCMEC boils it down to 25 tips in 25 minutes.

Elizabeth Smart Foundation developed radKIDS to "resist aggression defensively."

Missing children hotline: NCMEC 24-hour hotline (800-THE-LOST or 800-843-5678). The site also has an online Push to Talk system.

Cybertipline receives tips on sexually exploited minors (1-800-843-5678)

Age of vulnerability:

Parents do worry about the flipside, that generations have grown up overprotected and fearful. That milk-carton campaign partly ended because it scared kids.

Missing children appeals showed up on milk cartons across the nation throughout the '80s, but by the end of the decade, the program began to fade out, primarily due to concerns over its efficacy and complaints by pediatricians that the photos frightened young children. "People weren't really paying attention to the images on the milk cartons," the center's Bob Lowery told the San Jose Mercury News. "The only ones paying attention were younger children enjoying their cereal." (April 20, Time)

"Our children are smarter and better educated and more worldly" than previous generations about the dangers, but Lowery agrees there has been a trade-off. Knowing the brutality out there "instilled a sense of vulnerability in all of us ... it changes us as a society ... We're not as trusting as we used to be, but we need to be educated of the dangers out there." And, he adds, what the case of Etan shows to parents and victims is that no one forgets. "We're going to continue to look for children."