Gallaudet raises the bar for ‘DeafSpace’ architecture

By Amy Rose Dobson, Curbed DC

Hansel Bauman stamps his feet on the hard floor of one of Gallaudet University's buildings. The high-pitched echo from his boots reverberates back, and Bauman raises his eyebrows. "That isn't good," he says. Bauman, director of Gallaudet's campus design and planning, goes on to explain that all those sounds—echos, squeaks, and chair scrapes—get picked up by hearing aids and generate extra noise into the ears of their owners. "Acoustics are one of the most important parts of DeafSpace design," he says.

At Gallaudet, a D.C. university for the deaf and hard of hearing, ambient noise is just one of the things that keep Bauman's mind in overdrive. Every aspect of the campus's buildings gets his attention, down to minute details that hearing people would probably never think of.

Currently Bauman and his team are concentrating on a new dorm expected to be finished in time for students to move into this fall. "Many of our students come from hearing families, so this is the first time they've been in a community of people who communicate the same way they do. We want to support that as much as possible," he says. Curbed toured the in-progress dorm last week and found a lengthy list of ways simple changes to a building can drastically improve the lives of people who have little or no hearing.

The photo at right shows the lobby Bauman used as an example of bad acoustics. "We're trying to learn what we did wrong so we can figure out how to do it better in the new building," he explains. New techniques include installing absorptive panels on the upper parts of walls to absorb excess sound and using flooring materials that don't create as much unnecessary noise.

Embedded in the very name of DeafSpace is another top priority for this architecture movement: the need for more space. People without hearing loss can carry on a conversation while they walk and be parallel to each other without losing track of what the other person is saying. Hearing impaired people need to be able to see the other person and watch where they are going. That creates the need for more of a 45-degree angle between the participants and automatically increases their need for more physical space. Gallaudet realized the hallways need to be much wider than usual, and the ones in this new dorm are about seven feet wide, two to three feet wider than commonly-sized halls, so people can carry on signing conversations more easily.

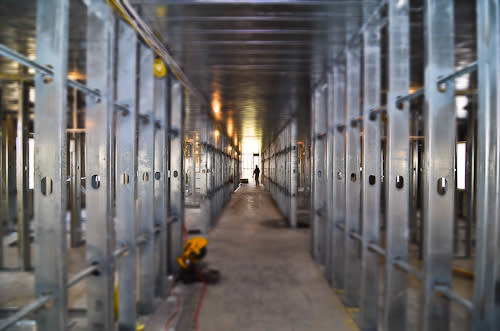

Another hallway feature involves alcoves in front of each dorm room, as shown at right. They create more space for people to move out of the way of hallway traffic as well as create a wider threshold of entry into the room. "Since hearing impaired people can't see someone coming, there's always this sense of sudden interruption," says Bauman. "We are working with MIT on various vibration technologies so hearing impaired people can feel someone arriving at their doorway." Currently, Gallaudet uses a light switch system outside each door. Instead of knocking or ringing a doorbell, people announce their arrival by turning on and off a dedicated light.

The next picture shows the in-progress stairwell for the new dorm, which helps open up the lines of sight so students can have advance warning of someone arriving. "We try to find the balance between visual access and visual exposure," says Bauman. "We want people to feel safe and not have the sense that someone can sneak up on them, but we also want people to have privacy."

Next is a look at the first floor, which includes a large empty space called the Co-Lab for student performances, art shows, or meetings. The wide angle of the shot shows the emphasis on bringing as much natural light into the building as possible, but aesthetics are only one reason for the large windows. Communication is another. Because sign language is a visual language, it is important to see subtle changes in facial expressions: The lighting in a room can change the tone of a conversation. Even the most innocent of smiles can look sinister when backlit by a setting sun, explains Bauman. His team has taken things one step further by adding filters to the windows that polarize the light and reduce glare. Natural light also helps reduce eyestrain.

Here we have a look at the two-person dorm room space. The design team presented several different floorplan choices, and students voted on the one they liked best. The five-story building will have rooms for 175 students, plus several faculty apartments. Most of the living spaces are built for a typical roommate set-up, but there are several rooms on the ground floor built as singles for people with physical disabilities. Each floor has a common kitchen and living room.

In the foreground of the picture at right, you can see the materials that are planned for the exterior. The goal was for this to be a "background" building so it wouldn't compete visually with the original buildings on the campus (many of which were designed by Frederick Law Olmstead in the 1800s).

Now we're back to the building we started in, with the acoustically inferior lobby, to show examples of "datums," or visual clues that the space is changing. The columns on the left, for example, are an extra hint that the building edge is ending and opening up into wider space. Other datums can be a change in the baseboards and wall color or material to delineate one room from another. The new building will include some similar features, but they won't be installed until it is closer to completion. Another detail that many would overlook is the use of sliding glass doors that lead into the building. They allow people to enter without having to stop signing and pull open a door handle.

Curved walls are a trend that has increased in DeafSpace architecture as a way to prevent two people from walking into each other if they come around a corner at the same time. Since they might not be able to hear footsteps, the curve allows them an earlier glimpse of each other, but Bauman is not convinced it is a good solution. "All it does is encourage people to walk closer in to the wall so they end up not being able to see around the corner. The walls should still come to a point, but the top half should be glass so people can see if someone is coming," explains Bauman as he demonstrates in the photo above.

All these pictures are just the beginning of DeafSpace principles and just the beginning of how this building is at the forefront of new design trends (we didn't even get into its geothermal heating system, for example). Bauman and his team have a research paper coming out next year that outlines 150 ways the design of a building can impact the experiences of people who are deaf, but he doesn't admit to having too many firm answers. "I look at it as 150 research questions," he says.

More stories from Curbed DC:

D.C.'s third most expensive house sale of the year

Curbed Cup Round 3: Logan Circle vs. U Street

Curbed DC is looking for a writer. Might that be you?