Bloomberg’s “Nanny State”: Refuting opposition to the “new” public health

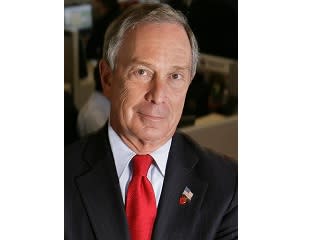

As Michael Bloomberg leaves the mayoralty his health legacy is bitterly contested. During his three terms in office he sought to remake the city, shaping decisions on diet, tobacco, physical activity, and firearms (see Table). Many of his policies have served as models nationally (and even internationally) such as posting calories (adopted in the Affordable Care Act), the trans fat ban (proposed by the FDA), and smoke-free public places (now in most major cities). Over 20 food companies adopted his voluntary salt-reduction guidelines. But, Bloomberg’s policies have also drawn the ire of vocal critics and sometimes the rebuke of judges.

Two controversial moves came just as he was leaving office—a portion limit on sugary drinks and a tobacco purchase age of 21 years (the highest in the nation). The courts struck down the portion limit, but the case is now on appeal to New York’s highest court. And critics expressed amazement that an 18 year-old can drink alcohol, drive a car, and enlist in the military, but now cannot buy cigarettes in New York City. (See my essay in the Hastings Center Reporthttp://www.thehastingscenter.org/Publications/HCR/Detail.aspx?id=6536).

The public broadly accepts the exercise of infectious disease control powers, for example, to stop the spread tuberculosis, SARS, or novel influenzas. But they often bristle at the “new” public health, aimed at the growing obesity epidemic—causing diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. Critics frame their arguments in intellectual terms, claiming that chronic disease policies are unproven scientifically, inconsistently applied, unfair to minorities, and undemocratic. I want to dispel these intellectual arguments, and then get to what is really bothering a vocal segment of the public—the belief that government has absolutely no justification for reaching into the lives of adults, who are perfectly capable of making choices for themselves.

The “Absence of Science” Claim

Critics challenge Bloomberg’s policies because they are not backed by scientific studies. This is slightly disingenuous because the real concern is not that the policies will be ineffective, but that they actually will work, driving consumers away from widely sold foods—e.g., sugary drinks, chips, cookies, and fried goods. Corporations with vested interests have been the major backers of campaigns against these policies The insistence on scientific proof is just a way to stall or block public health innovations. Logic and research does guide Bloomberg’s policies. Even the soda portion limit (perhaps the hardest case) is supported by research showing that sugary drinks deliver empty calories; consumption is directly associated with rising obesity rates; and portion sizes have grown exponentially as the obesity epidemic has unfolded.

But whether or not there is definitive science is almost beside the point. Rarely are policymakers expected to demonstrate a certainty, or even high probability, of “success” in other domains. Imagine asking legislators to prove that their economic policies work, such as the push for fiscal austerity. We understand that in a world filled with complexity, we cannot show that a particularly policy will lead to a clear result, but critics demand it of public health. And how is it even possible to show something works unless it is first introduced and then tested?

The “inconclusive science” critique is also faulty because it focuses on a single intervention. The incidence of tobacco use has plummeted nationally, and in New York City in particular. But do we know why? It is unlikely to have been precipitated by any single policy. Rather, a suite of policies, operating over time, changed the culture of tobacco—e.g., smoke-free environments, taxes, mandated warnings, and curbs on advertising. If a suite of food policies were implemented, might we see the same changes in dietary patterns over the next two decades? Imagine that tomorrow, government banned trans fats; taxed foods with excess sugar and salt; mandated prominent and non-confusing nutritional labels; subsidized fruits and vegetables rather than high-fructose corn syrup; and changed zoning and development to favor supermarkets over fast foods. We might see a slow and steady change in America’s food culture. And the same could be done to promote physical activity, with bike shares and safe paths, attractive pedestrian walk-ways, parks, and so forth.

The “Inconsistency” Claim

Related to scientific uncertainty is the demand for consistency across all similar products. Critics derided the soda portion limit because it applied to McDonald’s supersized drinks but not to 7-Eleven’s Big Gulps or Starbucks Flavored Lattes. The inconsistency critique, however, fails to understand the nature of law making. Law is forged through ugly political compromise—shaped by public preferences, lobbying, and trading favors among politicians. Politics is the art of the possible, not the perfect. Essentially, critics are saying, “We hate the portion size ban for its Nanny intrusiveness, but it won’t work because it’s riddled with exceptions.” The implication is that critics would accept the limit if it applied more broadly, which clearly is not their intent. A tax on sugary drinks would have been a more logical intervention than portion control, but New York State has been unwilling to impose a tax, despite Bloomberg’s requests.

The “inconsistency” claim also misunderstands the importance of incremental improvements in public policy over time. In the realm of public health, agencies tackle problems one at a time, hoping to build a critical mass of policies in the long run. Insistence that policy makers solve every problem now or not at all is a recipe for doing nothing.

The “Slippery Slope” Claim

Critics worry that Bloomberg’s policies – even if relatively benign in themselves – will lead to ever-more invasive policies in the future—e.g., if the mayor can ban trans fats or restrict sugary drink sizes, this opens the door to regulating any unhealthy food. A host of vested corporate interests can make common cause around slippery slopes—e.g., the sugar, alcohol, and tobacco industries, along with restaurants and advertisers. All of these groups stand to lose if health is placed at the center of public policy.

Slippery slope arguments should be approached with suspicion, as they force a speculative analysis without any specifics about the policy feared to lie downslope, or the likelihood of its being manifest. The task of policy makers is to delineate which policies are acceptable and which are not. Their adoption of any given policy does not suggest that they will extend the same reasoning in other realms. It should not be necessary to win a debate today about policies that may, or may not, be proposed in the future.

Slippery slope arguments, moreover, lack normative force because all sides in a debate can level them. A move in the direction of anti-paternalism, for example, could set government on a slippery slope towards neglecting acute health problems. Policymaking is about striking a reasonable balance based on available evidence.

The “Free Speech” Claim

Corporations wanting to sell unhealthy foods, tobacco, or alcohol intentionally conflate the public’s interests with their own economic interests. Businesses claim that consumers have a right to smoke, eat, or drink their products, however unhealthy. This defense of consumer rights wrongly implies that corporations are being socially responsible. Where their posturing as champions of consumer rights fails, companies invoke their own liberties.

When government tells corporations what they must (labeling requirements) or must not (marketing restrictions) say, businesses clothe themselves in the First Amendment. Big Tobacco repeatedly asserts the right to market its hazardous products. Using free speech arguments it has blocked municipal and federal attempts to compel graphic warning labels.

The mayor’s most recent tobacco initiative – forcing retailers to keep tobacco products hidden from the public’s view – will similarly provoke a First Amendment challenge. Bloomberg’s intent was to shield children from marketing and prevent impulse buying by former smokers. The Convenience Store Association called the bill “patently absurd.” “No other retail business licensed to sell legal products is required to hide them from its customers.”

The “Justice” Claim

Because obesity- and tobacco-related diseases fall primarily on African Americans, Latinos, and the working class, interventions necessarily apply disproportionately to those groups. This means, of course, that any intrusion on autonomy or privacy will fall primarily on the vulnerable. Tobacco taxes, for example, are regressive mostly affecting the poor. Industry and civil libertarians have joined together to decry the injustice of health measures that tread disproportionately on the liberty of the poor and minorities. This is a curious conception of justice, however, because it focuses solely on the fair distribution of the downsides of obesity or tobacco policies—i.e., limits on liberty. The justice argument fails miserably in weighing the corresponding health benefits to the poor.

Government’s failure to act to reduce suffering and early death visited mostly in poor neighborhoods is the far greater injustice. Suppose the ban on trans fats or soda portions facilitates healthier diets; cigarette taxes reduce smoking; or that surveillance results in better diabetes management. If policies work, a negligible limit on unfettered choice seems a very small price to pay for ameliorating the devastation to the individual and her family from chronic diseases. Health should be seen as a primary freedom, as it underwrites so many of life’s options.

The “Undemocratic” Claim

The courts have taken Mayor Bloomberg to task for circumventing the elected city council in several of his policies, notably the soda portion limit. The trial court in the soda portion case remarked that he had “eviscerated” the separation of powers. Courts blocked several other Bloomberg initiatives (e.g. vehicle emissions) due to questions of procedure and authority. He has issued more executive orders than mayors Koch and Giuliani combined. His design changes in the city streetscape (e.g., pedestrian plazas and bike lanes) began as pilot projects, with no public hearings.

It remains an open case as to whether an appointed Board of Health can regulate on its own initiative without the blessing of the legislature. Those concerned with procedural regularity condemn the exercise of unilateral power, while those seeking health impacts welcome strong leadership. Undoubtedly, checks and balances are valuable elements of a robust democracy. The question is whether a chief executive has a duty to cut through political logjams to achieve collective goods, or whether working within the legislative structure is always required.

The “Paternalism” Claim

As I indicated above, I don’t believe that any of these intellectual arguments are what is really bothering critics. Their discomfort with Bloomberg’s agenda, at its core, is grounded in distrust of government telling autonomous adults how to conduct their lives. Many believe that the state should not interfere with personal decisions that primarily affect the individual but not others.

Most of Bloomberg’s policies are not all that intrusive, and certainly not as burdensome as the underlying diseases. Nutrition, physical activity, and tobacco control policies are not morally equivalent to quarantines or forced treatment. Often they represent nothing more than a return to the norms of the recent past—such as smaller food portions and more livable spaces. Other interventions actively create a “new normal” such as reduced trans fat, sodium, and sugar, or limiting advertising to children. Once implemented, many interventions are embraced; few of us are nostalgic for the days of smoke-filled restaurants and workplaces.

For those who continue to believe in personal responsibility, consider a simplifying hypothetical. When a corporation sells an unhealthy product to a consumer, there is no level playing field; it is exceedingly hard for the individual to make the healthy choice. The corporation has an economic incentive to sell that product irrespective of the harms that ensue. The government helps make that product cheaper by subsidizing the ingredients (e.g., high fructose corn syrup) and more accessible by enacting zoning laws that make fast food retailers virtually ubiquitous. The courts grant the corporation free speech rights to market aggressively with deceptive messages about health, fun, and vitality—often targeting youth. And the poor, uneducated consumer may not have comprehensible information or even affordable access to healthier alternatives. All in all, those burdened with meeting monthly bills and juggling jobs and families find it easier to make the choice that is less expensive, more convenient, and deceptively marketed. The default choice in today’s America is the unhealthy choice, but we can change that default without undermining anyone’s fundamental freedoms.

The bottom line is that elected officials should be held accountable for the health of their inhabitants. Those who disrupt the status quo, such as Bloomberg, have thus far shouldered the burden of accountability, facing fierce criticism and industry backed judicial challenges. But the vast majority of public officials have stood by and done nothing amidst skyrocketing obesity rates. It is time for the political class to be held accountable not for trying to make the population healthier and safer, but for failing to act in the face of manifest suffering.

Lawrence O. Gostin, an internationally acclaimed scholar, is University Professor, Georgetown University’s highest academic rank conferred by the University President. Prof. Gostin directs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and was the Founding O’Neill Chair in Global Health Law.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Supreme Court won’t hear Internet sales tax challenges