Boy’s passport leads to high-stakes Supreme Court showdown

One word on a boy’s passport years ago has led to a big-time showdown involving all three branches of the federal government on Monday, as the Supreme Court referees a dispute over Israel between Congress and two Presidents.

The case in front of the nine Justices today is Zivotofsky v. Perry and it involves 12-year-old Menachem Binyamin Zivotofsky. Menachem’s parents are American citizens, and Menachem was born in Jerusalem.

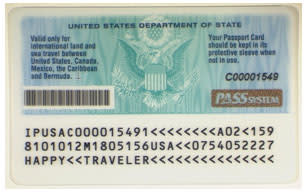

Citing a 2002 law passed by Congress and signed by President George W. Bush, with reservations, the Zivotofskys asked the State Department for a passport for Menachem when he was two-months-old that listed “Jerusalem, Israel,” as his birthplace.

Israel and Palestinians are locked in a long-running sovereignty dispute over Jerusalem. The United States government has tried to remain neutral in the dispute.

The Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 2002 directed the State Department to “record the place of birth as Israel” in the passports of Americans born in Jerusalem, if the children born in Jerusalem or their parents requested it.

President Bush had attached a signing statement to the Act, saying he believed it was unconstitutional. (When President Barack Obama took office in 2009, his administration agreed with the Bush administration.)

Back in 2002, the State Department refused to add the word “Israel” to Menachem’s passport, and the dispute has been in the legal system since them.

In 2012, the Supreme Court first heard the Zivotofsky case, and it rejected arguments that the debate was purely political, and the case was sent back to a lower court. A year later, the District of Columbia Circuit Court ruled on the side of the executive branch, stating that the President has the exclusive power to recognize other nations.

The Supreme Court accepted the case for a second time (it only takes four Justices to grant a hearing for case), and the Justices have two significant, historical issues in front of them.

The direct constitutional issue is the question of which branch of government controls all, or at least most, of the foreign policy decisions in Washington.

The direct political issue is the current United States foreign policy of it not recognizing Jerusalem as part of Israel. A Court ruling that would favor Congress could be interpreted overseas as a de facto American recognition of Israel’s claim to Jerusalem, which would have major policy consequences.

There has been a lot of discussion among legal scholars about the Zivotofsky case since April, which has mostly focused on the ability of Congress to regulate passports.

The supporters of the Zivotofsky argument point to the lack of any direction from the Founders that granted an exclusive power to the President to recognize a foreign nation; numerous passport laws passed by Congress since 1856; the ability of Congress to regulate immigration and foreign trade laws; and a Taiwan-People’s Republic of China recognition question resolved by Congress in 1994.

The supporters of executive powers believe the Founders were very clear that Article II reserved foreign policy powers to the President, including the powers to nominate ambassadors and to make treaties. These two powers depended on the ability of the President to recognize foreign nations, the supporters say.

The sides clearly disagree on the intentions of the Founding Fathers when it comes to recognizing foreign states, and the implications of a famous Supreme Court decision from the 1950s: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

The Youngstown decision barred President Harry Truman from taking over steel mills during the Korean War and curbed presidential powers. A critical concurrence in 1952 from Justice Robert Jackson stated that, “when the President takes measures incompatible with the expressed or implied will of Congress, the authority of the President is at its lowest.”

The Zivotofsky supporters draw direct parallels between their case and the Youngstown case. The executive powers supporters believe the Youngstown example isn’t valid, because Congress unconstitutionally stepped on the President’s exclusive power to recognize nations.

As a footnote, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid doesn’t agree with the Obama administration in this case.

“The law does not alter the position of the United States on the status of Jerusalem,” Reid said recently. “Rather, it continues Congress’s century-and-a-half-old exercise of legislative authority over the contents and design of identification documents, such as passports, held by U.S. citizens.”

Recent Stories on Constitution Daily

Would a new Senate majority abuse the budget reconciliation process?

Before the NSA, there was the USPS

Constitution Check: Do the federal courts lack the authority to rule on same-sex marriage?