California agrees to sharply cut use of solitary confinement

By Sharon Bernstein

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (Reuters) - California will release hundreds of inmates confined for years in solitary confinement into units where they will live with others, in a sweeping settlement announced Tuesday to reform the practice of keeping prisoners in near-isolation for decades.

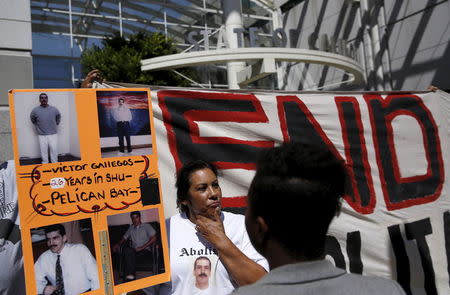

The settlement ends a lawsuit originally brought by prisoners at the state's Pelican Bay maximum-security facility, where some lived for decades housed alone in their cells for up to 23 hours a day, plaintiffs' lawyers and state officials said.

“This settlement represents a monumental victory for prisoners and an important step toward our goal of ending solitary confinement in California, and across the country,” inmate Todd Ashker and other prisoners who filed the initial complaint in 2009 said in a joint statement Tuesday.

As outlined in the agreement, most inmates held in Security Housing Units for more than 10 years will be released into general prison populations, and inmates will no longer be confined to such units for unknown periods of time.

California's practice of keeping prisoners in solitary or severely segregated units for decades has drawn increasing criticism from human rights activists, who say it is torture, and unconstitutional.

The settlement comes amid increasing clamor nationally for prison reform at both the state and federal level.

In 2013, nearly 30,000 inmates went without meals as part of a hunger strike protesting California's use of solitary confinement, thrusting the issue into the national spotlight.

As part of the settlement, as many as 1,500 inmates, or about half the total population in solitary or near-solitary confinement, will soon be moved either into general prison populations or special units where they will have higher security but be able to interact with others, said Jules Lobel, an attorney with the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights.

The state also agreed to no longer sentence inmates to such units for indeterminate periods that can stretch to decades. It also agreed to only send inmates to the units if they commit certain felonies while behind bars, not just because they have gang affiliations.

Jeffrey Beard, California's prison chief, confirmed the terms of the settlement and said it was part of a longer-term shift by the state away from such heavy reliance on near-isolation for inmates.

It marks a dramatic turn away from practices instituted in the 1980s as a way to control prison gang violence.

"We have to remember that 35 to 40 years ago there was a lot of violence in the system," Beard said. "There were staff and inmate murders, and the gang violence was spilling out into the streets."

In a practice that will be dropped as part of Tuesday's settlement, inmates were sent to Security Housing Units if they were shown to be affiliated with prison gangs. Sentences were indeterminate, and some were held there for more than 40 years.

Inmates complained that these placements were sometimes based on connections as tenuous as having the name or photograph of a prison gang member in one's cell.

The state has consistently rejected the term solitary confinement to describe Security Housing Units, saying inmates have up to 90 minutes per day out of their cells, and that at Corcoran and other state prisons some have roommates.

Under the settlement, inmates could still be sent to Security Housing Units for up to five years for crimes committed in prison. Those who remain in the units will have more opportunities to interact with others and will have access to out-of-cell programming for 20 hours per week.