Chancellor Hammond chooses his battle - fixing weak productivity

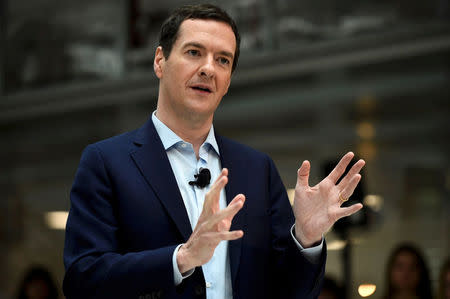

By William Schomberg LONDON (Reuters) - In 2011, early in his time as Chancellor, George Osborne said he would revive British manufacturing as he promised "a march of the makers" to rebalance the economy. But nearly six years on, the economy is just as reliant on the services sector. This week, Osborne's successor Philip Hammond staked out his own priority: turning around Britain's long-standing productivity problem to meet the challenges of leaving the European Union. Hammond used his first budget statement to address what he called the "shocking" gap between productivity growth in Britain and almost all other large rich countries, something which threatens to gnaw away at the economy and workers' wages. "We lag the U.S. and Germany by some 30 percentage points. But we also lag France by over 20 and Italy by eight," he told parliament on Wednesday. "Which means in the real world, it takes a German worker four days to produce what we make in five, which means, in turn, that too many British workers work longer hours for lower pay than their counterparts," he said. "That has to change if we are to build an economy that works for everyone." Hammond put money behind his pledge, saying he will borrow 23 billion pounds ($29 billion) to invest more in housing, transport and digital infrastructure and research over the next five years. Beyond 2020, he promised to increase investment in economic infrastructure to between 1.0 and 1.2 percent of economic output each year, up from 0.8 percent now. While modest in terms of overall spending - Hammond also announced a 122-billion-pound increase in government borrowing, limiting his budget options - the decision to borrow in order to invest represented a break with Osborne's more rigid approach to running the public finances. Whether Hammond has more success with productivity than Osborne did with manufacturing remains to be seen. The challenge already looks tough. Britain's budget office expects that leaving the EU will hurt the ability of companies to grow as they scale back on investment and find fewer migrant workers to fill their vacancies. The Brexit hit to productivity is expected to require an extra 18 billion pounds in government borrowing over the next four years, the Office for Budget Responsibility has said. QUICK START? Executives with some infrastructure firms questioned whether Britain can move ahead with the kind of urgency promised by Hammond on Wednesday. A decision to approve new airport runway capacity for London took 25 years and other major projects have been slow to get going, often as a result of Britain's complex planning system. John Hicks, UK head of government and public for AECOM, a U.S. engineering firm, said the new infrastructure funding might have to wait for government agencies to announce a pipeline of projects with a clear positive impact on productivity. "It's a really good admirable aim, but to a certain extent I think what he's subtly doing is raising the bar for project viability," Hicks said. Britain's business minister Greg Clark told Reuters the investment plan was focussed on the long term and he would be providing details of its next steps soon when he published the new government's industrial strategy. "This is very much with a view on the medium and long term horizon rather than a countervailing response to Brexit. It's not that kind of short-term stimulus," he said. But Yael Selfin, head of UK macroeconomics at financial services firm KPMG, said the government had put more of a focus on areas which would help the private sector including road improvements which would probably be quick to carry out. More investment in infrastructure that encourages private house-building could help to ease a lack of homes on the market which has discouraged workers from moving around the country, another drag on productivity growth, she said. "It feels more focussed in terms of purpose this time round," she said of Hammond's announcement. However, Selfin and Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a think tank, both said Hammond had not addressed one of the big factors behind Britain's productivity problem - a lack of skilled workers. "We spend less on research and development than most of our competitor economies, so that does hold us back," Johnson said. "You kind of know what kinds of roads work and where to build them," he said. "We've struggled for decades and probably a century to work out what the right thing to do on the education system is." (Additional reporting by David Milliken, William James and Sarah Young; Editing by Louise Ireland)