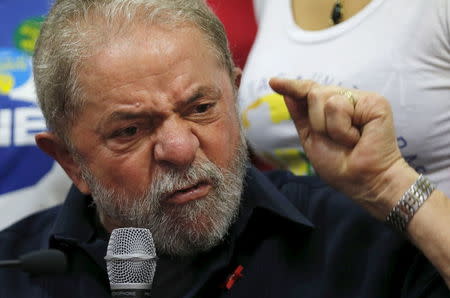

Charges, threat of jail cast Brazil's Lula in familiar role: martyr

By Paulo Prada RIO DE JANEIRO (Reuters) - Criminal charges and a request by prosecutors to jail Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva are putting the former Brazilian president and leftist icon back in a role he has long relished: that of the martyr. The 70-year-old former metalworker, still a hero to blue-collar Brazilians because of an economic boom that created millions of jobs during his two terms as president, has known since his days as a union leader how to cast himself as the victim of an oppressive elite, galvanizing the working class behind him. Last week, after federal police took him into custody briefly for questions about a far-reaching graft probe around Brazil's state-run oil company, Lula said he "felt like a prisoner" and urged leftist organizations, from landless peasants to labor unions, to rally. "Summon me," he said, asking them to show support. "I am going to travel this country." For the beleaguered government of President Dilma Rousseff, Lula's successor and protégée, any traction Lula gets could provide relief at a time when it is crippled by impeachment proceedings, an economy that shrunk by 3.8 percent last year and a corruption scandal that is drawing ever closer to her inner circle. "This is a paralyzed government that needs any help it can get," says Carlos Melo, a political scientist at Insper, a São Paulo business school. "Even if Lula himself has lost some support, he still knows how to mobilize the party militants. The government will hitch a ride on that." Of course, Lula's circumstances are far different from four decades ago, when he mobilized hundreds of thousands of workers against a military dictatorship and played a role in restoring democracy to Latin America's biggest country. Federal prosecutors say they believe Lula accepted illicit payments and favors connected to the giant kickback scandal around Petroleo Brasileiro SA, the oil company. In a separate, but related investigation, state prosecutors in São Paulo, Brazil's industrial capital and the cradle of Lula's Workers' Party, have charged him with crimes including fraud and money laundering. Lula has denied any wrongdoing. 'AN ACT OF INJUSTICE' The widening scandal, and the allegations against him, have eroded the popularity of Brazil's first working-class president, who enjoyed approval ratings of nearly 90 percent when he left office at the end of 2010. In a recent Datafolha poll simulating the presidential election in 2018, when Lula could attempt to return as the Workers' Party candidate, he had 20 percent of the vote, slightly less than the centrist candidate who heads the chief opposition party. On Thursday, the state prosecutors asked a judge to jail Lula, pending further legal proceedings. The move was criticized as slipshod by many jurists, who argue that a world-famous leader poses virtually no flight risk. Rousseff, in comments to reporters on Friday, said the request "exceeds the limits of good sense, is an act of injustice." Even Workers' Party rivals said it could provide ammunition for those who characterize the ongoing investigations as a witch hunt. Indeed, in a statement late Thursday, Lula's defense cast him as a historic underdog still fighting oppression. The request is an effort "to gag a political leader, to impede his expression of thought and even the exercise of his rights," wrote Cristiano Zanin Martins, one of Lula's attorneys. "Only in the dictatorship, when all rights of the citizen were suspended, were opinions and the exercise of rights reason to deprive liberty." Rousseff on Friday said she would be proud to have Lula in her government, referring to the possibility that the government could shield Lula by appointing him to her cabinet. Under Brazilian law, that would require any legal charges against him to go before the Supreme Court. People familiar with the possibility, however, say that Lula is unlikely to accept such an offer, because doing so could be interpreted as an admission of guilt. More likely, they say, Lula will continue efforts to rally what's left of his political base. On Sunday, opposition groups have scheduled the latest in a series of demonstrations to express support for Rousseff's ouster. In addition to ongoing impeachment proceedings, launched last year over accounting tricks in the government budget, Rousseff faces a court decision over the alleged use of kickbacks to finance her 2014 re-election campaign. Rousseff denies both sets of accusations. So far, the demonstrations have been lackluster, composed mostly of upper and middle-class whites who traditionally oppose the Workers' Party. But the growing tension has led some government leaders to ask leftist groups to refrain from inciting clashes of the sort that erupted between supporters and opponents outside Lula's home and the São Paulo airport where he was questioned last week. "You have a government that may not conclude its term and the prospect of Lula in jail," says Alberto Almeida, a consultant at the Instituto Analise, a political and social analysis firm in São Paulo. "They (the Workers' Party) are at the point where the only defense is to attack." (Reporting by Paulo Prada; Editing by Mary Milliken)