Chile aims to focus summit on its brighter side

World leaders treated to wine, salmon and glowing statistics as Chile hosts summit

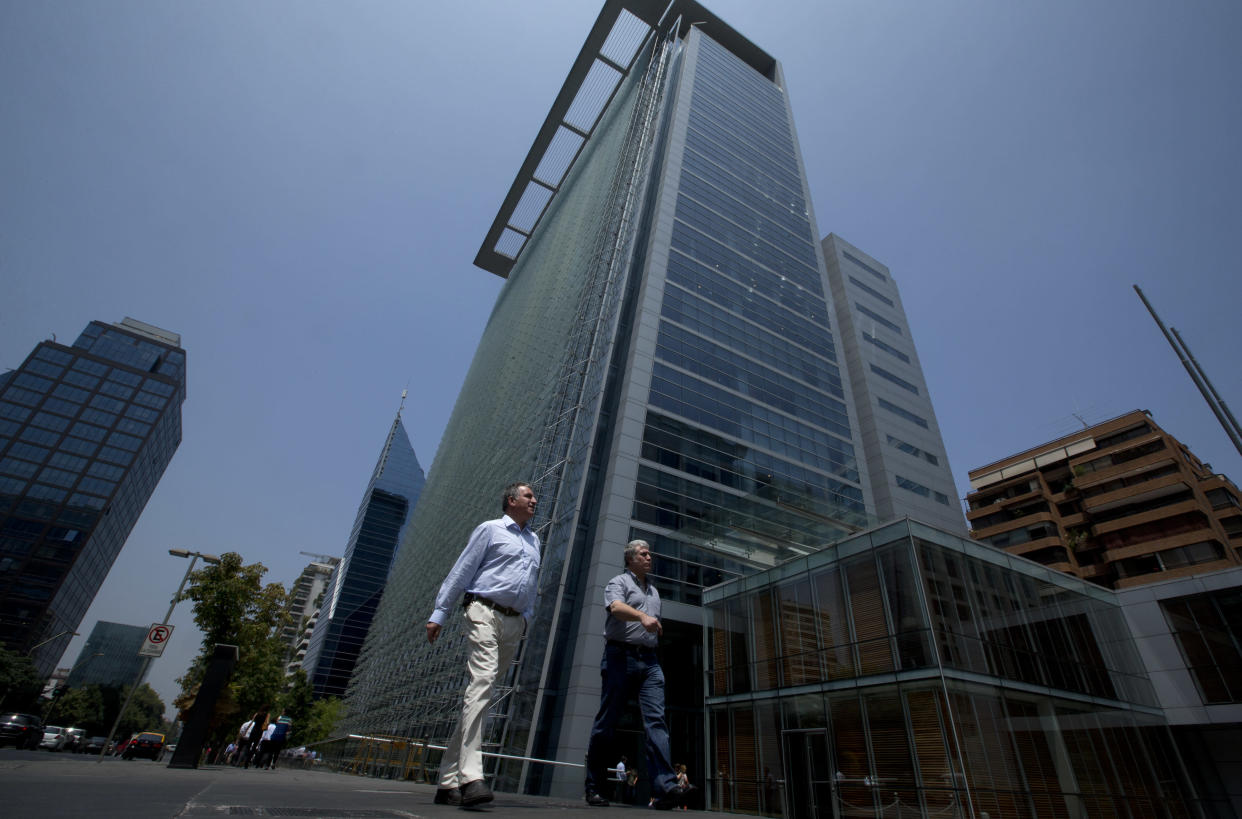

People walk past high risers in the financial district of Santiago, Chile, Thursday, Jan. 24, 2013. European, Latin American and Caribbean leaders gathering for this weekend’s economic summit will likely see only one side of Chile _ the polished, upscale country where tourists and investors stay in five-star hotels in a sparklingly clean financial district nicknamed “Sanhattan,” well away from Santiago's slums. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) -- European, Latin American and Caribbean leaders gathering for this weekend's economic summit will likely see only one side of Chile — the polished, upscale country where tourists and investors stay in five-star hotels in a sparklingly clean financial district nicknamed "Sanhattan," well away from Santiago's slums.

Hundreds of security agents will ensure that presidents and prime ministers won't be exposed to activists demanding a wider distribution of Chile's copper wealth and decent educations for all. They also won't hear Mapuche Indians denouncing the dictatorship-era anti-terror laws used against Chile's largest indigenous group.

This 16.5 million-person Andean country has won worldwide acclaim for its modernizing economy and institutions, rarities in a region still struggling to leave behind centuries of economic dysfunction. Yet there's another side to the Chilean miracle, one that will sit just blocks from the conference halls and hotels where leaders will meet this week.

Chile, in fact, has the worst inequality rate among the 34 countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, which includes other emerging economies such as Mexico and Turkey, according to the World Bank. Its rate of inequality is also worse than several Latin American countries with lower average incomes, including Peru, the Dominican Republic and Ecuador.

"Chile is a country of contrasts. We have two countries, and the people who come to the summit will only see one of them - 'Sanhattan' and the macroeconomic data," said pollster Marta Lagos.

"It might be good for the government that the people in the summits don't realize this, but it's bad for Chile."

Promoting sustainable development by fighting poverty, reducing income inequality and protecting natural resources are actually primary goals of the summit, which brings together more than 60 nations from the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the world's leading non-governmental organizations.

European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso, Spanish President Mariano Rajoy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are among those joining a business conference Friday where 300 executives are formally seeking joint ventures with the same goals.

International Monetary Fund Director Christine Lagarde framed their challenges starkly at last week's Davos Conference, saying the world's top executives agree that "severe income disparity" poses the greatest risk to the global economy in the decade ahead. "Excessive inequality is corrosive to growth; it is corrosive to society," she warned.

Other countries, however, can take many positive lessons from Chile.

The world's top copper producer is seen as probably the best managed economy in Latin America because of its strong growth, prudent fiscal and macroeconomic policies and strong institutions that make it an investor's paradise.

But critics say policies launched under former dictator Augusto Pinochet that privatized much of the country are still blocking urgent social reform and fostering social exclusion and inequality.

Pinera's government has been hit by wide protests demanding improvements in education, housing and health care and the protection of the environment from business interests. So while the country is expanding quickly, Chileans are asking for reforms to a system that they say still fails many.

Some of Chile's contradictions are in plain sight. Slum dwellers living in wooden shacks with zinc roofs at Campamento Juan Pablo II have a perfect view of elegant mansions, soaring skyscrapers and luxury car dealerships, just across a wide avenue in Las Condes, one of Santiago's wealthiest neighborhoods.

"The social gap is huge. The millionaires are right there next to us and we're stuck here living in this shantytown. The rich continue to get richer while the poor get poorer," said Raul Sanchez, 51, who earns poverty-level wages watching over cars at nearby parking lots.

No one can deny that President Sebastian Pinera has tried to fight poverty by encouraging job creation and giving cash handouts to the poorest of the poor.

But he has fallen far short of his campaign promise to eradicate poverty by the end of his term in 2014, and Chileans perceive the wealth gap as wider than ever, Lagos said.

Displaying economic success is particularly important to Chile, which is eager to be seen as a developed nation. Chile's business elites take particular pride in the country's membership in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The country's economy is expected to grow around 4.8 percent in 2013, outpacing every other country in the region but Peru, according to the United Nations.

Chile's strong standing has helped it weather the world economic crisis and withstand the contagion in the Euro zone, where the economy contracted by 0.5 percent last year. Along with mining, Chile enjoys strong consumer demand and profits from exports of salmon, forestry, wine and fruit. During a recent visit to Santiago, International Monetary Fund Director Christine Lagarde praised Chile for being one of the fastest growing economies in South America and keeping unemployment at historically low levels while controlling inflation below a target 3 percent.

"Chile has been a successful country and there are many reasons why Chileans should be proud, but the country remains largely unequal despite progress," said Patricio Navia, a Chilean political scientist who teaches at New York University.

"Precisely because it has grown so much, one wonders why the government hasn't been able to do more to fight inequality."

Far from the summit's headquarters in a heavily guarded conference center in the Andean foothills, protesters were preparing to take the streets for a "people's summit" on Friday.

Students are demanding an end to the decentralization of education in Chile, which has created a system of failing public schools, expensive private universities, unprepared teachers and pricey student loans.

Mapuche Indians are demanding autonomy and a return of their ancestral territory in Chile's Patagonia region, where timber companies, foreign corporations and wealthy individuals control most of the land. Environmentalists are demanding an end to the privatization of Chile's water, another legacy of the Pinochet era.

The most common complaint of the protesters is that wealth and power has been concentrated in very few hands.

"The biggest problem in Chile is that the differences between the haves and the have-nots are very dramatic," Navia said. "So you are not likely to see poverty as you see in other countries, but you will see that wealth and income in Chile are very unequally distributed."

___

Luis Andres Henao on Twitter: https://twitter.com/LuisAndresHenao