Citizen Scientists Reveal Wildlife Changes as Sea Ice Melts (Op-Ed)

Seabird McKeon a biodiversity scientist with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

As governments negotiate the best ways to reduce emissions and switch to renewable energy production, scientists are struggling to observe all the global changes taking place. Increasingly, citizen scientists are stepping in to monitor the shifts, a positive step in an uncertain path forward.

In particular, birders and whale watchers are documenting wildlife sightings and revealing shifts in animal movements in the planet's northern hinterlands. These patterns are key for understanding how melting sea ice is influencing species' ranges, and health, in the decades to come, as my co-authors and I discuss in a paper published recently in the journal Global Change Biology.

Traveling the Northwest Passage

As Arctic sea ice melts and waterways open in the Northwest Passage, so too does the prospect of an Arctic transit for shipping and mineral exploitation. These are remote waters, but the ships will have company: Marine birds and mammals are already starting to make the trip from one ocean basin to another — becoming what we call "interbasin taxa."

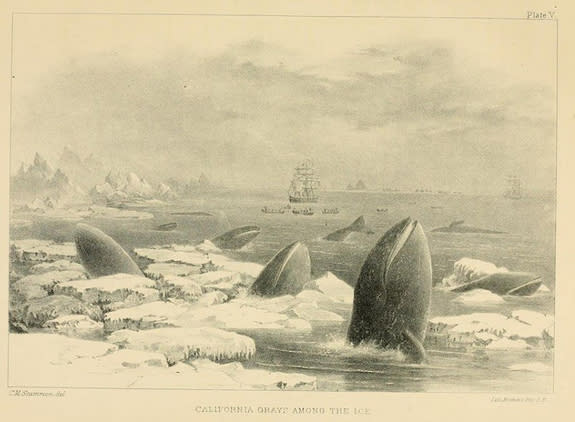

Gray whales, for example, have been pushing their limits at the ice boundaries for a very long time. Human hunting extirpated gray whales from the North Atlantic hundreds of years ago, where they were separated from the Pacific population by sea ice boundaries. With the opening of the Arctic passages, Pacific gray whales might be starting to break through to reclaim territory in the Atlantic. In 2010, keen-eyed observers spotted the first gray whale seen in the Atlantic for hundreds of years.

Enter the birders

Odd, individual animals that show up in unexpected places (like the gray whale) are referred to as "vagrants," and are the bread-and-butter of the competitive end of birding (yes, it's a thing). So it should come as no surprise that birders have been among the first to notice interbasin vagrants that might be using melting Arctic passages.

In the late 1980s, increased numbers of small seabirds called Manx shearwaters started appearing in the Pacific Northwest. This is an Atlantic species. Shearwaters are long-range migrants, so it was at first conceivable that the vagrants had flown around the southern tip of South America, and up the West Coast before starting to colonize the North Pacific. But then gannets were sighted off the coast of northern Alaska, raising the possibility of seabirds also using the Arctic passages.

The northern gannet is a spectacular white seabird with a 6.5-foot (2 meters) wingspan, and requires open water to fish. Normally found in the North Atlantic, at least one gannet set up shop in the Farallon islands off central California in 2012 and has been in the area ever since. Even population-level differences within bird species are discernible to the most hardcore birders, and Bruce Mactavish of Washburn University spotted Pacific common eider among the wintering Atlantic eider in Newfoundland.

Connecting the dots

In our paper, we identified more than 70 species that could potentially become interbasin taxa based upon their current range. Some, like the Atlantic gray whale , may wander like lost tourists, while others, like the Manx shearwater, may decide to move in. The first movements are likely to be rare and difficult to detect unless specifically targeted. And that is where the collective efforts of many people become crucial.

Many of the observations in our study were made by citizen scientists, motivated by a passion for wildlife and spending time outside, and are representative of the contributions that anyone can make toward our scientific understanding of global change. They follow three principles: Observe. Record. Share.

Citizen-science platforms such as iNaturalist, eBird and the National Phenology Network are allowing each of us a chance to record critical baseline data about our world. Perhaps it is when the flowers in your garden first bloom, or when you hear the first spring peeper.

Our combined efforts will help to reveal patterns, like that of interbasin taxa, at a pace that traditional science just can't keep up with. And with the climate changing at record pace, we need all hands on deck.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.