Clinton’s Campaign Manager Isn’t Worried About a 2008 Repeat

Robby Mook isn’t worried about his job.

In fact, he seems rather taken aback when I ask him if he hopes to avoid the same fate as Hillary Clinton’s first presidential campaign manager, Patti Solis Doyle, after Clinton placed a dismal third in the 2008 Iowa caucuses.

Mook, 36, leans back in a chair in an empty office in the Clinton campaign’s virtually deserted Des Moines headquarters. With less than seven hours to go before the caucuses, almost every last staff member and volunteer is out knocking doors, as Mook himself has spent the last three days doing. He hooks one jean-clad and sneakered foot around a chair leg as he leans back against the wall.

“We're sticking together,” he says, presumably speaking of his close-knit young staff, who many in the campaign refer to as the Mook Mafia, “all of us, every day, working in service.”

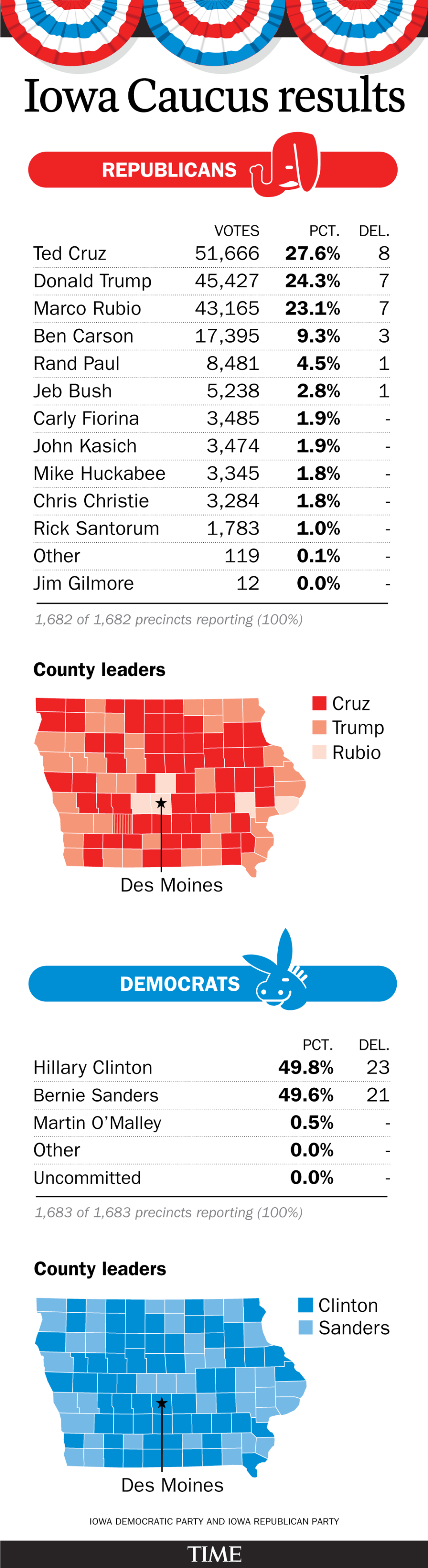

About 12 hours later the world would learn that Clinton eked out a slim victory in Iowa, so the question was moot. But Mook needn’t have worried either way. Mook, in many ways, is the antithesis of Doyle, 50, who was a longtime Clinton aide dating back to her years as First Lady picked more for trust than for campaign expertise.

Mook’s career in presidential politics began with a Vermont firebrand. Not Sen. Bernie Sanders, who has been giving Mook and Clinton a run for their money this cycle, but Sanders’ rebel forefather, former Gov. Howard Dean. Mook grew up on the New Hampshire/Vermont border. He started in local politics before becoming the deputy head of field for Dean’s 2004 presidential bid working in Wisconsin and New Hampshire. That was where he first learned about technology in campaign organizing—an interest he would take with him to run or help many other gubernatorial and senatorial races across the country.

Read More: Clinton Sounds a Progressive Note in New Hampshire

By 2006 Mook was working in the Middle East for the National Democratic Institute, a group sponsored by the Democratic Party that helps promote democracy abroad. There, he heard the name Clinton. A lot. “I remember speaking to a Palestinian man who was so critical of President George W. Bush, but then hearing him talking about Bill Clinton landing in the Gaza Strip and how much that meant to them,” Mook recalls. So, he started reading up on the President who was elected when Mook was just 12 and the apple of the eyes of his Dartmouth professor father and hospital administrator mother.

What Mook learned interested him enough that he moved back stateside and joined Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2007. He served as state director in Nevada, Indiana and Ohio. After her loss, he went back to working on other races, but retained many friends in Clinton circles: he ran Jeanne Shaheen’s successful Senate campaign in the fall of 2008 and Terry McAuliffe’s gubernatorial win in Virginia in 2013. Both Shaheen and McAuliffe have been close with the Clintons for decades.

Mook remained a fan of Clinton’s. “In 2008, I remember being impressed by how many people would come to events and ask her for help with a health issue or a special needs child and how she followed up on each and everyone of those people,” says Mook, who hoped to work for her again. By January 2015, he got his wish when he came on as a consultant for her and in April he was named her campaign manager, the first openly gay presidential campaign manager.

By all accounts, Mook was hired as much for his easygoing nature as for his expertise in ground game and harnessing the latest technology to get out the vote. He also was apparently hired for his talent for self-restraint. He refuses to criticize Clinton’s 2008 operation, simply saying that the times and the campaigns were different. And he’s self-effacing, always circling back to Clinton when asked what changed between the two cycles.

What’s different in the Iowa grassroots outreach? Clinton’s personal touch, he says, and her insistence on developing policies on issues she hears about from voters like drug addiction. Why is this campaign different tonally, less rallies more town halls? Because Clinton wanted to hear more from the people, he says.

What’s the biggest surprising difference between the two cycles? “It’s surprising how extreme the Republican Party has been and how difficult a time moderate voices have been to be heard,” Mook says.

Is he worried about indictments relating to Clinton’s State Department e-mails? “Republicans are out there throwing out all kinds of hypotheticals,” Mook says.

What happens if they lose New Hampshire? “I expect this to be competitive into March,” he says. “What all campaigns are trying to do is to build up a lead in delegates. I feel really good that we have a plan to March.”

Can they afford this? They are “very fortunate to have hundreds of thousands of donors 90% of whom give $200 or less,” Mook says. “We’ve had four of our top 10 fundraising days in January.”

But what if it drags on even longer? Are you prepared for a brokered convention? The chair snaps forward and Mook sits upright, his tailored red, white and blue gingham shirt creasing at the waist as he leans forward and half croaks, half laughs, “No!”