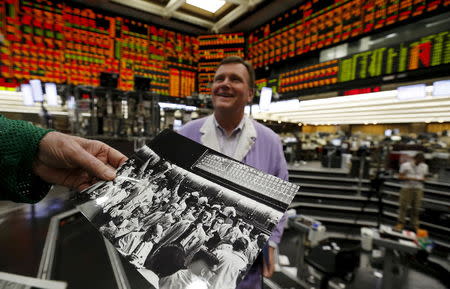

Closing of Chicago trading pits: a requiem for family ties

By Christine Stebbins

CHICAGO (Reuters) - Thomas Cashman was not long out of law school when his dad, Tom, brought him to the Chicago Board of Trade soybean pit in 1994. The two spent the next 10 years trading side by side, until Thomas moved upstairs to begin trading on computer screens.

Thomas, a third-generation CBOT trader now back practicing law and trading on the side, is a member of one of the better-known trading families in Chicago's 167-year history of futures trading. Over time, 24 Cashmans worked on the CBOT trading floor, all tracing their roots to the first Cashman on the floor: George, who came to the CBOT after high school in the late '40s. He later bought seats for his brothers Gene and Ed, both Chicago policemen at the time.

"It made it easier for me to break into the markets, but on the other hand I had that responsibility to live up to the family reputation,” said Thomas, speaking ahead of the planned closure of Chicago’s futures pits, expected as soon as July 6. "The whole family dynamic added to the honor of the system. I would never do anything to put a black mark on my family."

The Cashmans and other multigenerational trading families were a hallmark of Chicago’s commodity pits, their flailing arms and unique hand gestures a signature of the Chicago Board of Trade and its longtime rival, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The closure of open-outcry futures trading is bringing an end to surprisingly close connections among traders that have characterized the Chicago exchanges for decades.

In addition to the Cashmans, other prominent families included the names Stern, Brennan, Carey, O’Connor, Pietrzak, King, Hollander and Williams. “They created a community atmosphere," said Libby Mahoney, a historian with the Chicago History Museum, which has an exhibit focused on the Chicago pits. "There was a familiarity between the traders and that came from being handed down amongst many families.”

“The face-to-face encounters they had with each other created other connections that weren’t family but they became professional connections,” said Mahoney. “You’re going to see them the next day and the next day – you can build that kind of trust.”

A LIFETIME IN THE PITS

Tom Cashman, standing on the edge of the corn pit last month, recalled the morning in 1973 when his client, Cook Grain, ordered him and two other brokers into the pit. “I bought a couple million bushels, and they said keep going,” he said. As the market spiked that day, they bought contracts that controlled about 28 million bushels of soybeans. Only later did he learn the supplies were part of secret grain sales to the then-Soviet Union.

Tom Cashman, 76, is the last family member to go to the CBOT grain floor every day. His sons Thomas and Brendan, 48 and 43, still trade futures and options in Chicago, but both do so in front of electronic screens.

Tom's uncles sponsored him as CBOT member in the 1960s, and he traded through historic market events like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear plant and the Black Friday market crash of 1987.

“If you had family it was automatic: start as a runner, meeting people at different firms and working your way to branch out to your own firm,” the senior Cashman said.

The current patriarch of another longtime Chicago trading family, John Pietrzak, bought his CBOT seat in 1979, exactly 30 years after his father bought a seat. His grandfather started as a runner at the exchange in 1913 after a neighbor, seeing the boy hard at work cutting his grass, offered him a job as clerk on the trading floor.

By the time it was Pietrzak’s turn to try his hand at trading, Tom Cashman’s uncle, Gene, intervened on behalf of Pietrzak at the bank to help him get a $200,000 loan to buy his CBOT seat.

“It just so happens my grandfather had sponsored Gene Cashman for membership,” Pietrzak recalled with a smile.

For floor trader families, necessity often meant opportunity. Kelly King, the only child of fabled corn broker Richard "Whitey" King, began working on the trading floor in 1988 at age 15. A drought hit that summer, and with grain prices soaring, her father pressed Kelly King into service, handling the avalanche of paper orders coming into the pit.

She was hooked.

“It was rocking,” said King, the first and only remaining female corn broker in the pit. “Completely insane.”

King said she intends to stop trading once the pits close. She has obtained her real estate broker's license and is partnering with a friend.

On Feb. 6, when CME Group Inc , parent of the Chicago futures exchanges, held a meeting to inform traders of the decision to close the pits, a few complained loudly. Five months later, though, most sound sanguine about the pit closures.

“All stories have to come to an end. The markets will still go on,” said Thomas Cashman. “If you can figure out a way to participate then you can still be part of the game.”

Glenn Hollander, a CBOT trader for 40 years, says he transacts his grain deals electronically now. Hollander is a third-generation trader, and his son, David, joined the family cash grain business, Hollander & Feuerhaken, in 2002.

Hollander said he will miss being able to “read” the trade flow in the grain pits from his perch nearby, trading on a screen near the edge of the soybean options pit.

“There’s lot of expertise and a lot of history that is going to be lost, a lot of understanding of why the market is doing something,” he said. “I think open-outcry died because as electronics came in the people who were afraid of them didn’t embrace them. And pit traders just got swept away like a tsunami.”

(Editing by David Greising and Matthew Lewis)