Seabirds may eat so much marine plastic because of its scent

Our rising plastic consumption and growing appetite for beef are endangering bird species around the world, scientists said this week.

Two separate studies found that our consumer habits are affecting birds more profoundly than we previously thought. Researchers said their work could help inform conservation efforts to protect birds on both land and at sea.

SEE ALSO: Hawaii's bees are now protected under U.S. Endangered Species Act

The papers were both published Wednesday in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances. The first study explores why seabirds are so inclined to gobble up marine plastic pollution.

Image: AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe

Plastic bait-and-switch

With trillions of pieces of plastic floating in the oceans, about 99 percent of the world's seabird species are expected to suffer from plastic ingestion by 2050, a 2015 study found.

Birds often mistake bags, bottle caps, plastic fibers and other materials for food and swallow the plastic, damaging their insides and potentially killing them. Yet little research exists into why plastic confuses birds in the first place, according to researchers at the University of California, Davis.

Image: J.J. Harrison

Gabrielle Nevitt, an ecologist at UC Davis, and her former graduate student Matthew Savoca found that the smell of algae on marine plastic debris may be what attracts seabirds.

Algae leaks a sulfurous compound when it's dying or in distress. When tiny crustaceans feast on algae, the sulfurous scent sends a chemical message to seabirds: "Here is food."

In Nevitt's earlier research, she found that petrels, an abundant species of tube-nose seabird, have used this olfactory cue to forage for thousands of years. But that skill turns against petrels when the algae forms on plastic.

"The birds don't want to eat the algae. They want to eat what's eating the algae," Savoca, the lead author of Wednesday's paper, told Mashable. "Now [the compound] is telling them where to find the plastic."

Image: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Savoca and Nevitt made this finding by tying plastic beads wrapped in mesh bags to ocean buoys. The team collected the beads three weeks later, then took the haul to UC Davis' Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science. Researchers confirmed that the marine plastic reeked of the same sulfur compound released by algae.

Savoca noted the study is just the "first early evidence" that scent is a key reason why birds eat plastic and said further field research is still needed to validate the findings.

Mapping habitat loss

Birds are a critical part of any ecosystem: They disperse seeds, pollinate plants and recycle nutrients back into the ground. Because the welfare of birds often points to the overall health of their environments, the new research has consequences far beyond the bird nest.

"If there are problems with birds, then there are almost certainly problems with mammals and amphibians," said Stuart Pimm, a professor of conservation ecology at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment.

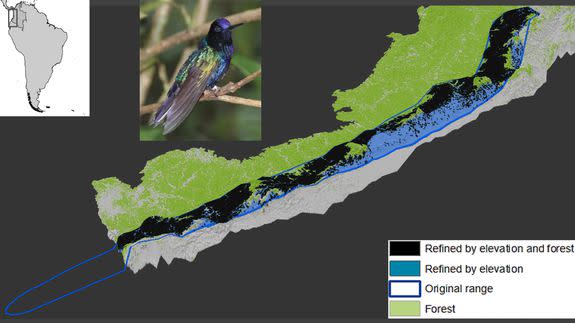

Pimm co-authored a Wednesday paper that used satellite imaging, remote-sensing data and field work to measure the habitats of bird species worldwide.

They found that hundreds of species are at risk due to land-use changes such as deforestation and industrial agriculture.

Image: NATALIA OCAMPO-PEÑUELA

The study fills a critical knowledge gap in conservation research, the authors said.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is responsible for monitoring and listing threatened species around the world, but its methods don't always incorporate modern data tools.

The Duke study found that more than 200 bird species at risk of extinction are not included on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species. Those birds are found in six rapidly developing regions: Brazil's Atlantic forest, Central America, Colombia's western Andes, Sumatra, Madagascar and Southeast Asia.

"We were surprised by how extensive the problems are," Pimm told Mashable.

Image: Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela

The widely respected Red List helps governments and conservation groups set legal protections and create restricted areas for threatened species. By adding satellite and mapping tools, conservationists would have a much deeper understanding of where birds are in trouble and need extra protection, Pimm said.

The study also found that more than 600 species in those six developing areas are seeing their habitats shrink from land-use changes. Of that group, only 108 species are classified by IUCN as at risk of extinction.

"Preventing these extinctions requires knowing what species are at risk and where they live," Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela, the study's lead author, said in a statement.

Stuart Butchart, who is responsible for the Red List's assessment of birds, said Pimm and his co-authors misunderstood the list's criteria and, as a result, incorrectly identified many species as not appropriately marked as threatened.

He said IUCN developed guidelines and material precisely to prevent the researchers' errors. "All Red List assessments are carefully reviewed before they are published to ensure that the criteria are applied correctly and consistently," Butchart told Mashable by email.