Coral Thrive Off U.S. Atlantic Coast, But Threatened (Op-Ed)

Ali Chase is a senior ocean policy analyst at the NRDC. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

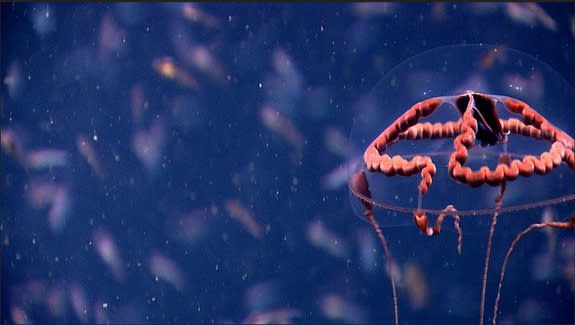

A hidden world thrives more than a mile and a half beneath the waves, in the inky blackness roughly 80 miles offshore the Atlantic's coastline. There you can find corals in all colors of the rainbow and a menagerie of sea life with evocative names, such as the whiplash squid, dumbo octopus, sea butterfly (which is actually a snail), sea toad and tonguefish. See more images of the deep-see life in "Exotic Deep-Sea Canyon Life at Risk (Gallery )."

Scientists know little about this amazing life offshore and the vibrant gardens of deep-sea coral communities, but thanks to a series of U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)-led explorations over the past several years, what they have recently uncovered is remarkable.

Today, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) released a new report, "The Atlantic's Deep Sea Treasures: Discoveries From A New Frontier of Ocean Exploration," cataloguing many of the new findings since 2011, and urging policymakers in the U.S. mid-Atlantic states to protect these vulnerable and biologically-rich ecosystems now, before it's too late.

More than 40 coral species have been identified on the NOAA Atlantic coast expeditions, at least three of which are believed to be new to science. Some are so abundant that scientists described them as coral "forests." Species of red, black, bubblegum, stony and soft corals have all been found, a number of which were never before known to exist in this region. In Baltimore Canyon offshore Maryland, scientists found a colony of bubblegum coral — so named for their bulbous, pink, branch ends — nearly 15 feet (4.6 meters) tall.

Deep-sea corals often have the same vibrant colors and tree-like shapes as their tropical cousins, but do not need sunlight to survive. These coral communities are sanctuaries, providing food and shelter for a range of deep-sea creatures, including potentially new species of sea stars and sea slugs, as well as rarely seen creatures — such as the Greenland shark, considered the slowest of all fish species — and a species of hydromedusa jellyfish that had last been reported in the region almost a century ago.

Despite such marvels, the Atlantic's deep-sea coral communities are at risk . They are highly vulnerable to harm from some fishing practices, such as trawling, that pull their fishing nets along the ocean floor, tearing the coral up. The corals are slow-growing, with some species growing only less than an inch (1.5 millimeters to 2.5 millimeters) each year. One pass of trawl gear can destroy corals that have been growing for hundreds, even thousands, of years.

Because of their depth and rugged topography, the deep-sea coral communities off the Atlantic coast have been largely sheltered from harmful bottom trawling. But as traditional fish species become overfished or markets change, fishing will continue to move into deeper waters and more difficult terrain.

To address that risk, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, which manages U.S. fisheries resources in that region, is currently developing a plan to protect deep-sea coral communities off the Mid-Atlantic coast from fishing gear damage. Called "Amendment 16," the Council intends to add this to an existing fishery management plan and will submit it to NOAA for approval. The public will have the opportunity to weigh in on this plan when it's released for comment, likely in early 2015.

Scientific findings like these challenge our imagination, and NRDC looks forward to commenting on the plan to protect these resources for us and future generations.

To learn more about the efforts to protect the Atlantic's corals and to see more images and video, view NRDC's site on ocean canyons.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.