Cuban doctors tend to Brazil's poor, giving Rousseff a boost

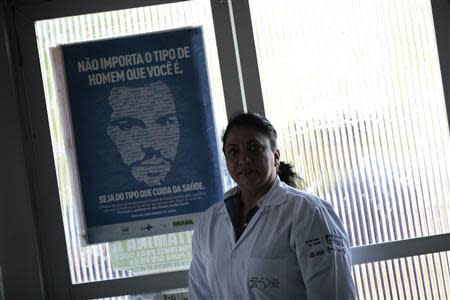

By Anthony Boadle JIQUITAIA, Brazil (Reuters) - They were heckled and called slaves of a communist state when they first landed, but in the poorest corners of Brazil the arrival of 5,400 Cuban doctors is being welcomed as a godsend. The program to fill gaps in the national health system with foreign doctors, mainly from Cuba, could become a big vote-winner for President Dilma Rousseff as she eyes a second term in next year's election despite fierce opposition from Brazil's medical class. The move to tap Cuba's doctors-for-export program begun by former leader Fidel Castro became a priority for Rousseff after massive protests against corruption and shoddy public transport, education and healthcare services rocked Brazil in June. Within weeks, she launched "Mais Médicos", or "More Doctors", a program to hire foreign physicians. Brasilia signed a three-year contract to bring thousands of Cuban doctors to work in poor and remote areas where Brazilian physicians prefer not to practice. Under an agreement that will earn cash-strapped Cuba some $225 million a year, Cuban doctors have been deployed to health centers in the slums of Brazilian cities and villages across the drought-stricken Northeast that had no resident doctors. Bahia state is reopening rural health centers that were unstaffed. Inhabitants of Jiquitaia, a hamlet surrounded by cacti, goats and famished cattle in Bahia's interior, no longer have to travel 46 kms (30 miles) on a dirt road to see a physician. "This is a gift of God," said farm worker Deusdete Bispo Pereira after he was seen for chest pains by Dania Alvero, a doctor from Santa Clara, Cuba. "Everyone is happy she is here. We're afraid she will be sent away," he said. Elderly residents and pregnant women crowded into the family health center waiting for a check up with Alvero, who like many Cuban doctors is an expert in preventive medicine. "There are illnesses here that I had only read about in books, like leprosy, which no longer exists in Cuba," she said mixing Spanish and Portuguese words. DOCTORS FOR RENT Cuba has sent doctors abroad for decades to help developing countries for ideological reasons, revolutionary foot soldiers first sent out by Fidel Castro onto a Cold War chessboard, from Algeria and Ethiopia to Angola and Nicaragua. Plunged into economic crisis after the Soviet Union collapsed, Castro devised a doctors-for-oil scheme with the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez in 2000. The so-called Barrio Adentro plan, in which more than 30,000 Cubans work in healthcare in dirt-poor shantytowns ringing Caracas and other cities, earned Chavez loads of political goodwill among the Venezuelan populace and was paid for with preferential oil shipments to Cuba. Even though most of the income goes to the Cuban government, Cuban doctors are delighted to go abroad because they can earn much more than they are paid at home, where doctors' salaries max out at the equivalent of $50 a month. "We don't get paid much, but we are not here for the money. We are here to help our country, which is poor," said Lisset Brown, who works at a neighborhood health center in Ceilandia, the largest slum ringing the Brazilian capital of Brasilia. The arrival of 12 Cuban physicians has relieved the overburdened Ceilandia hospital and improved the credibility of the public health system, said Brazilian nurse Tania Ribeiro Mendonça. "People see the government is doing something." Cuba has doctors to spare today. According, to the World Bank, it has the world's highest number of doctors in proportion to population: 6.7 per 1,000 people, compared to 1.8 in Brazil, though that ratio rises to 4 per 1,000 in cities where Brazilian doctors prefer to work, such as Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. MEDICAL UPROAR Brazilian doctors initially tried to stop the arrival of foreign colleagues, which they saw as an attempt to undermine their professional interests and medical standards. When an early contingent of Cubans arrived at Fortaleza airport in northern Brazil in August, angry Brazilian doctors shouted "Slaves!" at them. But they have had to tone down their criticism because opinion polls show that a vast majority of Brazilians favors hiring foreigners when local doctors are unavailable, even though doubts remain about the qualifications of the Cubans. One poll in November showed that 84.3 percent of those surveyed back the Mais Médicos program, though only 66 percent thought the foreign doctors were qualified to do the job. "We are not opposed to foreign doctors working here. They can come from Russia, England, Cuba or Bolivia but their degrees must be evaluated and the government is not doing that," said Florentino Cardoso, head of the Brazilian Medical Association. Cardoso, a cancer surgeon, complained that Rousseff has "demonized" Brazilian doctors by associating them with the many shortcomings of Brazil's healthcare system. Putting more doctors in outlying areas, he said, will not end lines for underfunded medical services in the cities. To allow foreign doctors to work in Brazil, Rousseff rushed through legislation allowing them to practice for three years without getting their degrees validated by local authorities, a cumbersome process that can take years. The law, however, says they can only work in basic healthcare services. MEAGER WAGES Having lost that battle, Brazilian doctors are now focusing their criticism on what they call unfair treatment of their Cuban colleagues. Unlike doctors of other nationalities, the Cubans cannot bring their families to Brazil, which opponents of the Cuban government say is to ensure that they return home. The Cubans get only a fraction of the 10,000 reais ($4,300) a month that Brazil pays for each physician in the program. Municipal health officials in Bahia said they provide free board and lodging to the Cubans, who get paid 800 reais a month in cash in Brazil. An additional 1,200 reais are paid to their families in Cuba, and 8,000 reais go to the Cuban government through the Pan-American Health Organization. While other foreign doctors can apply to work elsewhere in Brazil after their three years are up, the Cubans have to either go home or sign up for another stint with the More Doctors program. "We abolished slavery long ago but this looks awfully similar. It's not the best way to go about improving healthcare in Brazil," said Eleuses Paiva, a physician and congressman from a party that backs Rousseff's coalition government. 2014 ELECTIONS Barely four months off the ground, More Doctors is earning handy political kudos for Rousseff, who can point to the program as an example of her quick response to June's protests. More than one million Brazilians took to the streets at the time to vent their anger over inadequate public services that burn up taxpayer money and are infamous for long lines and waiting lists at national health facilities. More Doctors is a quick fix that might take time to show results in Brazil's health statistics, but Rousseff's campaign next year would receive a boost if she can, for example, tout a decline in infant mortality in the poorest parts of the country. It could also help Health Minister Alexander Padilha, the program's chief architect, get elected governor of Sao Paulo, Brazil's wealthiest and most populous state. "This is a big plus for her re-election. The polls show there is very high approval ratings for the program," said David Fleischer, professor of politics at the University of Brasilia. The program has been so successful that Rousseff's rivals are copying it. In Sao Paulo, a political stronghold of Brazil's main opposition party, the PSDB, the government is sending doctors to tend to the poor in the interior of the state. For Dr. Paiva, the congressman, More Doctors is an election campaign strategy more than a healthcare program. "The Cubans will inevitably work for Rousseff's re-election, funded with taxpayer money," he complained. In the northeast of Brazil, Cuban doctors are indeed winning hearts and votes for Rousseff. "They are humble and look you in the eyes, which Brazilian doctors don't do," said Angelo Ricardo, as he brought his ageing father to a health center in the Bahian town of Remanso. "Brazil needed this more human care. I'll vote for her, no question." ($1 = 2.3332 reais) (Editing by Kieran Murray and Christopher Wilson)