Don’t forget our evolving Constitution

As we celebrate the 226th anniversary of the American Constitution this week, it is important not to forget that the document drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 is far different from the one that governs our country today.

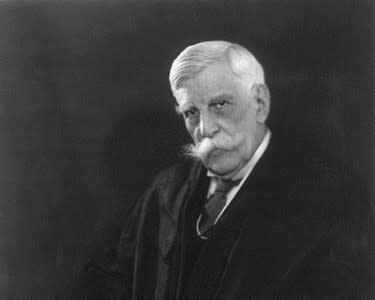

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Not only has the original constitution been formally amended 27 times, but our understanding of important provisions has changed radically as a result of our experience and the evolving needs of society.

No provision demonstrates this more clearly than the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. Ratified as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791, the free speech clause contains a seemingly straightforward command: “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech.” Yet in spite of its unambiguous language, for much of our history this clause was little more than an empty slogan.

Just seven years after the Bill of Rights was ratified, Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1798, which banned “false, scandalous, and malicious” statements about the federal government. Introduced by the Federalist Party as a way to silence its opponents, the Sedition Act cast a dark cloud across the political landscape. Newspapers were shut down, and 25 people were arrested, 10 of whom were ultimately convicted.

The Sedition Act expired in 1801 when the Federalists lost power, and incoming President Thomas Jefferson pardoned those who had been convicted under the law. But that didn’t mean free speech assumed a central role in our constitutional system. Far from it. As a result of the Supreme Court’s 1833 decision in Barron v. Baltimore, the First Amendment – along with the rest of the Bill of Rights – was held inapplicable to the states. This meant that for nearly a century the courts could not hear challenges under the federal constitution to restrictions of speech by the states.

When courts did consider free speech claims, they almost always ruled against them. In the 1870s, a number of challenges were brought against the Comstock Act, a federal law that prohibited the mailing of obscene material. Although it was used to block the distribution of a wide range of non-erotic material – from birth control ads to anatomy textbooks to the plays of George Bernard Shaw – the courts overwhelmingly rejected challenges to the act, ruling that the First Amendment did not protect speech harmful to the public morals.

In the early 1900s, the courts took a similarly limited view of the First Amendment. In a series of confrontations known as the free speech fights, cities across the country banned labor unions from spreading their messages on sidewalks and street corners. When those laws were challenged, the courts upheld them, ruling that the preservation of order outweighed the unions’ interest in expressing their views.

The Supreme Court was no exception to this trend. In 1907, it adopted the cramped English view that freedom of speech prohibits only pre-publication censorship but places no limits on the government’s power to punish speakers after the fact. And even when the Court renounced that view in the spring of 1919, it continued to defer to the government’s suppression of speech, upholding the convictions of Eugene Debs and other socialists who were prosecuted under the Espionage and Sedition Acts of World War I.

The turning point came later that same year when Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had written the opinion in Debs, had a change of heart. Dissenting from the Court’s decision to uphold the conviction of Russian anarchists under the Sedition Act, he wrote a passionate defense of free speech, arguing that “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas – that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

As I recount in my new book, “The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind – and Changed the History of Free Speech in America,” Holmes came to appreciate the value of free speech as a result of the influence of a group of young progressives, as well as the experience of watching his own friends attacked for their views. And the dissent he wrote was so powerful that it eventually prevailed, ushering in the modern, liberal era of the First Amendment.

But that didn’t happen all at once. The second Red Scare and the rise of McCarthyism posed a new threat to free speech, as leaders of the Communist Party of America were jailed for teaching the principles of Lenin and Marx. It was not until the 1960s that our current, expansive view of free speech firmly took hold in the courts. And even now our understanding of the First Amendment continues to evolve, as numerous questions about free speech are litigated in the Supreme Court every year.

The lesson of this short history is clear. The Constitution that was drafted in the summer of 1787 was a wonderful document. But it was just the start of what has been a long and continuing experiment in democratic governance.

To quote from another Holmes opinion, the words of the Constitution “have called into life a being the development of which could not have been foreseen completely by the most gifted of its begetters. It was enough for them to realize or to hope that they had created an organism; it has taken a century and has cost their successors much sweat and blood to prove that they created a nation.”

Thomas Healy is a professor of law at Seton Hall Law School. A graduate of Columbia Law School, he clerked on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and was a Supreme Court correspondent for The Baltimore Sun. He has written extensively about free speech, the Constitution, and the federal courts. The Great Dissent is his first book.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Congress, elections top concerns in Next 10 Amendments project

Should states determine if drones can record your conversations?

Five lessons we can learn from George Washington’s Farewell Address

The Constitution Outside the Courts: The Internal Revenue Service