Was Einstein right? Ripples in space-time may have been found

Are the rumors true? Whispers about a possible detection of actual ripples in space-time have been swirling for weeks, and on Thursday, the world may find out if one of Albert Einstein's boldest predictions is true.

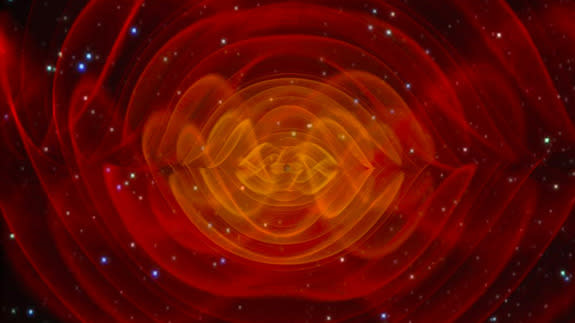

Einstein theorized that the collision of two massive objects like black holes would cause the fabric of space-time to warp.

SEE ALSO: New probe could help detect ripples from cosmic collisions, part of Einstein's theory of relativity

Think of space-time as a sheet on a mattress. If two bowling balls swirled around one another on that sheet, it would cause the fabric to ripple. This is how space-time moves, in theory, when black holes merge.

Those ripples move outward from the source, perturbing the space-time around various objects, including Earth. Theoretically, a sensitive enough instrument could detect that very slight perturbation, signaling that these gravitational waves exist.

So far, no one has yet detected these waves. But that may be about to change.

Scientists working with the National Science Foundation and the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory experiment (LIGO) — designed to hunt for these elusive gravitational waves from Earth — have announced a press conference scheduled for Thursday in Washington D.C..

The announcement of the news conference doesn't give away anything about the possible detection — in fact, the statement is pretty mundane — but it still has the scientific community buzzing.

The LIGO hunts for space-time's ripples using two huge instruments located in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington.

Each of the identical LIGO detectors is shaped like the letter "L" with a laser beam running down the length, splitting at the bend. The detectors, when used together, can measure minute changes in space-time by clocking the distance between the two arms of the observatory.

"Multiple interferometers are needed to confidently detect and locate the sources of gravitational waves (except continuous signals), since directional observations cannot be made with a single detector like LIGO, which is sensitive to large portions of the sky at once," LIGO wrote on its website.

If a gravitational wave passes through and changes the length of the arms by a tiny fraction of the diameter of a single proton, it would be enough to characterize the wave, according to the observatory's website.

LIGO was recently upgraded and completed a hunt for the ripples last month, so on Thursday, scientists and the public should get some sense of whether that new sensitivity was enough to find those hidden waves in space.