Einstein's gravitational waves detected in landmark discovery

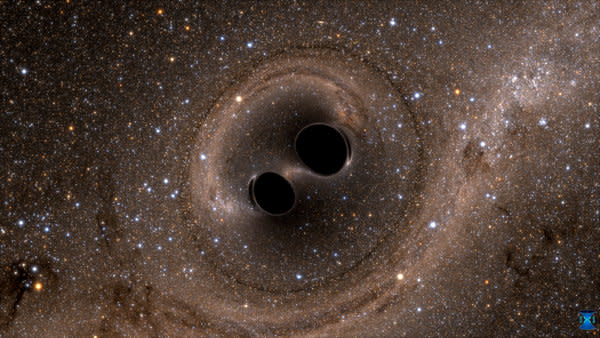

By Will Dunham and Scott Malone WASHINGTON/CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (Reuters) - Scientists for the first time have detected gravitational waves, ripples in space and time hypothesized by Albert Einstein a century ago, in a landmark discovery announced on Thursday that opens a new window for studying the cosmos. The researchers said they identified gravitational waves coming from two distant black holes - extraordinarily dense objects whose existence also was foreseen by Einstein - that orbited one another, spiraled inward and smashed together at high speed to form a single, larger black hole. The waves were unleashed by the collision of the black holes, one of them 29 times the mass of the sun and the other 36 times the solar mass, located 1.3 billion light years from Earth, the researchers said. "Ladies and gentlemen, we have detected gravitational waves. We did it," said California Institute of Technology physicist David Reitze, triggering applause at a packed news conference in Washington. "It's been a very long road, but this is just the beginning," Louisiana State University physicist Gabriela Gonzalez told the news conference, hailing the discovery as opening a new era in astronomy. The scientific milestone was achieved using a pair of giant laser detectors in the United States, located in Louisiana and Washington state, capping a decades-long quest to find these waves. "The colliding black holes that produced these gravitational waves created a violent storm in the fabric of space and time, a storm in which time speeded up, and slowed down, and speeded up again, a storm in which the shape of space was bent in this way and that way," Caltech physicist Kip Thorne said. The scientists first detected the waves last Sept. 14. The two instruments, working in unison, are called the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). They detected remarkably small vibrations from the gravitational waves as they passed through the Earth. The scientists converted the wave signal into audio waves and listened to the sounds of the black holes merging. At the news conference, they played an audio recording of this: a low rumbling pierced by chirps. "We're actually hearing them go thump in the night," Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist Matthew Evans said. "There's a very visceral connection to this observation." 'A NEW SENSE' "We are really witnessing the opening of a new tool for doing astronomy," MIT astrophysicist Nergis Mavalvala said in an interview. "We have turned on a new sense. We have been able to see and now we will be able to hear as well." While opening a door to new ways to observe the universe, scientists said gravitational waves should help them gain knowledge about enigmatic objects like black holes and neutron stars. The waves also may provide insight into the mysterious nature of the very early universe. The scientists said that because gravitational waves are so radically different from electromagnetic waves they expect them to reveal big surprises about the universe. Everything we knew until now about the cosmos stemmed from electromagnetic waves such as radio waves, visible light, infrared light, X-rays and gamma rays. Because such waves encounter interference as they travel across the universe, they can tell only part of the story. Gravitational waves experience no such barriers, meaning they offer a wealth of additional information. Black holes, for example, do not emit light, radio waves and the like, but can be studied via gravitational waves. Einstein in 1916 proposed the existence of gravitational waves as an outgrowth of his ground-breaking general theory of relativity, which depicted gravity as a distortion of space and time triggered by the presence of matter. Until now scientists had found only indirect evidence of their existence, beginning in the 1970s. Scientists sounded positively giddy over the discovery. "This is the holy grail of science," said Rochester Institute of Technology astrophysicist Carlos Lousto. "The last time anything like this happened was in 1888 when Heinrich Hertz detected the radio waves that had been predicted by James Clerk Maxwell’s field-equations of electromagnetism in 1865," added Durham University physicist Tom McLeish. Abhay Ashtekar, director of Penn State University's Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos, said heavy celestial objects bend space and time but because of the relative weakness of the gravitational force the effect is miniscule except from massive and dense bodies like black holes and neutron stars. A black hole is a region of space so packed with matter that not even photons of light can escape the force of gravity. Neutron stars are small, about the size of a city, but are extremely heavy, the compact remains of a larger star that died in a supernova explosion. The National Science Foundation, an independent agency of the U.S. government, provided about $1.1 billion in funding for the research over 40 years. (Reporting by Will Dunham in Washington, Irene Klotz in Cape Canaveral, Florida, and Scott Malone in Cambridge, Mass.; Editing by Tom Brown)