His Exit Interview? ‘Spectre’s Sam Mendes On His Role In The Dramatic Transformation Of James Bond

Beyond the “is it as good as the last one” debate that greets every James Bond film, the media narrative around Spectre has been all about whether Daniel Craig and director Sam Mendes are done. There is also a preoccupation over the financial stakes of a film whose reported $250 million budget means it won’t turn profit unless it grosses $600 million worldwide — a figure much lower than Skyfall‘s $1.1 billion, but almost exactly the amount reached by Craig’s two previous Bond films, Casino Royale and Quantum Of Solace. And there’s the angle that every studio in town is courting MGM and Danjaq to become 007’s new home, now that Sony’s deal is up and its champion, Amy Pascal, is off producing movies.

Lost in all back and forth is how Spectre concludes a creatively daring four-film evolution of 007 from a sometimes campy, flesh-and-blood Transformers robot and into an existentially tortured secret agent, facing mortality and the prospect of an empty retirement he’ll spend alone. And how Mendes, with his encyclopedic devotion to the Ian Fleming books and the past films, worked in lockstep with Craig to uphold a tradition while completely overhauling it. Certainly, that story will get its due someday. Hmm…Why wait?

DEADLINE: Your James Bond films has altered Hollywood’s longest-running film franchise, but your opening scene during the Day of the Dead celebration in Mexico upholds that tradition of 007 filmmakers finding visually appealing global cultural spectacles, and blowing them up.

MENDES: I assure you, we cleaned it all up. Day of the Dead is like your version of Halloween, only it’s a purer form, a celebration of the dead and the people you’ve lost. It’s not a funeral, or a wake, and there’s nothing morbid about it. People set up shrines around the streets to their loved ones. The only other time they had 120,000 people filling the Zocalo was for a Justin Bieber concert.

DEADLINE: Talk about a missed opportunity, James Bond and Justin Bieber.

MENDES: It wouldn’t have worked quite as well as what we did, but it might have, as the studio says, skewed younger.

DEADLINE: It would not be compatible with the sophisticated through line of this four-picture arc, spanning three directors. Bond bleeds existential crisis all through Spectre, going from the thrill-seeking unrepentant womanizer to weary warrior looking for some kind of commitment. Spectre‘s opening starts with the obligatory beautiful woman in a bedroom, but 007 doesn’t even make it back for that rendezvous and seems emotionally asleep until he meets Lea Seydoux’s Madeleine, and glimpses the kind of future he wanted but could not have with Vesper Lynd. Describe how you saw Bond as you assembled Spectre with Craig and your screenwriters.

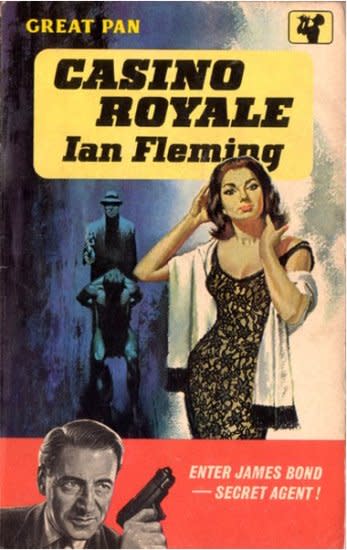

MENDES: Well, it does go back to Casino Royale, where the most difficult work on this current version of Bond as a character was done by Martin Campbell, and in the casting of Daniel Craig. The key factor there was, they worked on a script from an Ian Fleming novel, which they had never really done, not like that. And in that one movie, they eradicated camp. They eradicated Q, and Moneypenny. There were no self-reflexive jokes and no sense he was there with one foot inside and one outside the movie, simultaneously. That had been the lifeblood of the franchise for 20 years, Roger Moore through to Pierce Brosnan. Bond became this eyebrow-raising, knowing figure, unaffected by any kind of emotional journey. Those were wonderful action adventures that spanned the globe and Bond was the glue, but he had no emotional journey. And then suddenly, the character bled, literally and metaphorically, and fell in love with somebody and lost them. It was kind of creation of how Bond became hardened as a younger agent and after that never looked back. Quantum Of Solace was the second half of that story, and by the end of that he’d fully gotten over her.

DEADLINE: He avenged her death and then turned to stone, emotionally.

MENDES

: He became the machine and I inherited a much more complex character. Fleming created not a hero but an antihero, capable of good and bad. A womanizer who drinks too much, sleeps with too many women, smokes too much and disobeys authority. He hates people and the person he hates most of all is himself. That character had been gradually left behind by the franchise, so all I really did was go back to what I could find in the books. I had a decision to make, when I took on Skyfall. Do I watch all the movies again or none of them? I decided to watch none of them, including Casino and Quantum. I’d watched them when they came out, but I haven’t seen a frame from the day I said yes, five years ago. I wanted mine to be a version of Bond that happens in my head, but also, I didn’t want to be reminded of a different kind of Bond. I did go back to the books and I took lots of clues from them. When I re-read You Only Live Twice, there was all this weird stuff about him nearly dying and then effectively turning into somebody else. That’s what Skyfall is, to a degree. At the beginning of The Man With The Golden Gun, he tries to assassinate M. The whole idea of killing M and M being someone who might die, is introduced by Fleming in that book.

DEADLINE: So many Bond films, it’s surprising there was anything left to discover.

MENDES: The franchise at that period in history was not able to go that dark. By that time the Roger Moore movies were in swing, and who wanted to see a brainwashed Bond, trying to assassinate M? It would have been preposterous, given what they’d established. Although, not quite as preposterous as a man with three nipples which I still think is one of the most bizarre bits of Bond.

DEADLINE: Wait. What?

MENDES

: Christopher Lee as Scaramanga. One of his remarkable features is, he has three nipples. So at the beginning of The Man With The Golden Gun, if my memory serves me, the camera pans across his chest, revealing a third nipple. It doesn’t inflect it in any way, or tell you how to take it, or if it’s sinister or wit. It’s just there. He’s got another nipple. You’re like, OK…and? And nothing. He’s got three nipples. There was no psychological depth or insight like if he had a scar or a crippled hand, something that might have affected him. If you follow anything Fleming had written, there is psychological depth to Bond. There is depression, self-hatred, feeling dead, this self-destructive streak leading him out on to missions to feel alive, with a kind of devil-may-care kamikaze spirit that makes him more dangerous because he doesn’t care if he dies.

DEADLINE: What else did you find in the books that proved helpful?

MENDES: The family history of Bond as a child growing up in Scotland. Being orphaned after his parents died in a climbing accident, going to live with an aunt, and spending these winters with this man called Franz Oberhauser. Who, as Bond says in one Fleming book, “was a father figure to me at a time when I happened to need one.” That is all he says, but we took those clues and ran with them, to find the core of the character. All this allowed us to make Skyfall quite a dark, intense film in which Bond was weak for the majority, drinking a lot and trying to clean himself up. At various points, he was injured and couldn’t move, and you could argue at the end of Skyfall that he failed in his mission, which was to keep M alive. She died in his arms. This enabled us to play with tone even more, and for him to think about falling in love again, because the movie ultimately is about legacy. Does your job define you? Are you just your job, or more? If you’re a secret agent, do you live your life in secret and die, un-mourned, or are you going to leave something behind, and have somebody who loves and cares for you? That is what both of these movies are moving towards. And it is what attracted me and seemed a worthwhile thing to explore.

DEADLINE: I don’t think we ever saw past James Bonds feel much as they presided over what could be better described as sexy adventure romps than what you put 007 through.

MENDES

: And lest we forget poor old George Lazenby. Who came in they gave this poor guy a poison chalice. He had to turn to the camera…well, they asked him to turn to the camera, look into it and say, “This wouldn’t have happened to the other guy.” To me, that was a complete misjudgment on the behalf of the filmmakers. Disaster. He looked into the camera and talked about another actor, playing the role. What chance could he possibly have, from that moment on, after basically apologizing for being himself? Talk about cutting someone off at the knees before they’ve even started. That was not a good idea.

DEADLINE: Sounds like you used the books to figure out what to do, and the movies to figure out what to avoid.

MENDES: Well, there were things Daniel was determined to avoid. Asking for love, asking to be compared to the other guy, or, hope you like me as much as the last bloke. With Daniel, it’s “I don’t care whether you like me or you hate me. I’m going to play the role the way I want to play it”…and everyone was, ‘Oh, my god. Daniel Craig, he’s a terrible casting.’ But of course, that reinvigorated the franchise.

DEADLINE: What would he have said if you had asked him to say that Lazenby line?

MENDES: It would have been a two-word answer, with a big smile.

DEADLINE: Bond producer Cubby Broccoli built film’s longest-running franchise by being cautious about change that could hurt its longevity. His daughter Barbara Broccoli and stepson Michael Wilson are now the gatekeepers who’ve let you kill M, and make Bond a miserable man who bleeds. Anything they would not let you do?

MENDES: The strange thing is, one of the great things has been how Barbara Broccoli and Michael Wilson have been continuously supportive of the vision I brought. At the beginning, one of the things I said was, “If you don’t want me to acknowledge Bond’s aging, or allow me to do something like killing M, which seemed to me a great idea given where Judi Dench was in terms of her age…if you’re not going to let me do that, then get another director.” There would be no point in me doing this, when what got me going was the feeling I could do something new and interesting. To have this hopefully exciting action movie with the underpinning of a meditation on aging and mortality, loss and parents, and other stuff that interests me and emphasized the thing that Bond has always been light on. He’s always been very, very heavy on plot, but he’s been very light on story. There is no real story, only plot, and that to me is not a satisfying movie.

DEADLINE: Why?

MENDES: Character and story are everything. Plot is the mechanics of getting people from A to B, and working out how they meet and how they engage. As for the journeys they’re all on, that’s story, and there didn’t seem to be one. I was very clear and forthright about that, and they went with it. I think they were nervous, about Skyfall, that the audience would go, “Hang on a second. When we come to a Bond movie people want to escape. We don’t want to be told our wonderful hero is aging and looking like shit, and that our beloved M is going to die. That wasn’t in the contract. Please don’t do that. You took me by surprise.” Instead, what happened was the audience felt an investment in Bond that they hadn’t before, a vulnerably perhaps they hadn’t seen before. And they wanted more. That made possible what happens in Spectre, where you take him another stage and you can have him considering walking away. I don’t think I could have done that in the Skyfall, but it became a natural development to the narrative as opposed to a kind of giant imposition.

DEADLINE: There are all these rumors you and Daniel Craig are done. That would leave the producers with a changed franchise, and the need to find a new actor and filmmaker. In the past, all they needed was to suit up a new actor, give him a villain to chase, and cue the opening theme.

MENDES

: I grew up on Dr. Who, and its ideas of regeneration. People say, “Well, once you’ve acknowledged time passing and Bond getting older and characters dying, how do you continue the franchise?” And the answer is you regenerate, and you have to be as brave as when they cast Daniel, and when they let M die. They have to go off in a completely different direction, into regenerating mythology. You cast a new actor and find a new director, and make something totally new. I can, off the top of my head, give you three or four ideas for where it could go next. They’re all daring and big. To me, the enemy is repetition and laziness, and the great danger is not challenging the preexisting format. These are my two chapters of the Bond myth. Someone else is going to write a chapter or 10 or 50, because Bond is strong enough for that, and because there’s enough to play with.

DEADLINE: As a 55-year old pondering the back nine, I appreciated Bond’s emotionally tumultuous journey and dilemmas in this film, and then saw bloggers say the film dragged. Someone our age would expect a protagonist to see a chasm when he reaches 50, without a wife, without kids. You might tire of the empty bed-hopping and even the crazy, reckless danger won’t be enough. At the same time, every scene needs an action payoff. Is there an emotion to action formula when you try to place an iconic action franchise on an elevated storytelling track?

MENDES

: It’s more a question of storytelling rhythm, and my rhythm of storytelling is my own. I think it is the thing that defines a director. Rhythm of dialogue. I think also it’s one of the quickest turnoffs when someone is not on your rhythm. Like for example, I’ll take a positive example. I’ve sat in all Bennett Miller’s movies, absolutely gripped by the rhythm of his storytelling. I think he’s a brilliant filmmaker. But I was sitting next to a couple people who just weren’t on the wavelength. They were sighing and moving, and I came out thinking, “Foxcatcher is a great movie.” And they said, “I don’t get it.” And these were smart people, whose energy demanded the story go faster, and they were bored while I was gripped. There is a misunderstanding that there is a universal rhythm to storytelling. There just isn’t. The rhythm of these movies is very personal to me. They breathe in and breathe out. I don’t believe in movies that just breathe out, but if you are looking for just one long bang, go and see Transformers. I like movies that breathe in as well, and that is what I brought to this, and sue me if you don’t like it. Everyone has an opinion about Bond, so there’s no conceivable way of pleasing everybody. The job that you have is to cut out the white noise and make the movie you want to see and you must not compromise that.

DEADLINE: Let’s say you were Bennett Miller and you were testing Foxcatcher and saw those people shifting in their seats. How do you know when to stick to your guns, and when to take a valuable hint to pick up the pace or risk losing your audience?

MENDES: Because any artist has a sense of what is and isn’t right for them. It’s an inert muscle. It’s a very dangerous game you play when success is your only criteria. End of story. You learn gradually how to tell stories and when you fail, you have to have the strength to challenge yourself to go back to those things and do it again because you believe in something other than just success. If the only criteria is success you’re f*cked. You cannot just be about success. That’s why I find the NRG research screenings so difficult because it tries to make a science out of something that is absolutely subjective and if you go in trying to please everyone you’ll please no one. For me, it’s what you feel. It was possible for me to feel this way because I had a certain status going in. I didn’t need this franchise. It proved a wonderful, thrilling thing for me and it’s definitely given me more control of whatever I do next. But I felt strong enough to not bow to pressure, and to have scenes the length that I thought they should be. But having said that, I am very aware the obligations in how you construct these movies. I learned this in the theater, spending 20 years telling stories to audiences. Sitting alongside them every bloody time. You learn what to look for and when you need to change the rhythm of something.

DEADLINE: If

Skyfall had been your first movie instead of American Beauty, would you have had the confidence to make the Bond films the way you did, or would you have been able to resist those commercial voices and the whims of things like test audiences?

MENDES: No. But I couldn’t have made these, first. I wouldn’t have had the technical ability to make them, the confidence…I wouldn’t have known how to approach the larger scale side of the movies at that point in my career. I wouldn’t have had any power in the equation. I wouldn’t have been able to…

DEADLINE: Insist?

MENDES: Well, it’s not about insisting. It’s about knowing. It’s about having enough to refer back to that you’ve done to give yourself the strength to press on. To say, when I did Road To Perdition, this happened, and that’s how I solved it. Let me try that. You need a body of work, and reference points to dip into. So you can say, “I could do that in one take but I tried that in that other movie and always regretted not getting coverage.” Or, I got coverage on that scene and I ended up cutting, but I should have left it as one shot. Once you have that experience, you need to put blinders on, to a degree, and be single-minded in the making of movies like these.

DEADLINE: Isn’t that hard when the world feels such ownership of Bond?

MENDES: I went to Turkey on the last movie, got out of the cab and the guy said, “Welcome to Turkey. We’re thrilled Bond is shooting in Istanbul. May I just say the movies are so much better now that they’re not trying to be funny the whole time?” This is a guy carrying my bag. I said, “I agree. I think you’re right.” And I get to the counter, 20 seconds later, and the woman says, “Are you going to put some jokes in this one?” There’s no way to please everyone. Too many jokes, not enough jokes, too long, too short. Everyone has an ownership stake that goes back generations, and strong opinions. If you think about it too much, you’ll freeze. All you can do as a filmmaker is make the one you want to see.

DEADLINE: Daniel Craig owes one more movie, but was blunt in describing how unappealing another 007 would be for him in an interview just after the movie ended. Was this like asking as woman just out of the delivery room if she wants to have another baby?

MENDES: Yeah. Or my analogy is, you’re running your first marathon, and 200 yards from the finish line, some guy shouts, “Are you going to run another one straight away?” I get why Daniel responded the way he did. Again, a two-word answer is what springs to mind.

DEADLINE: It has made the “will they come back” question the recurring narrative in Spectre launch coverage. You’ve dodged it pretty well, but let me ask you this. After Skyfall, you both said much the same thing, that you’d had enough. And then you both came back for Spectre. What’s different now?

MENDES: Did Daniel say he’s had enough after Skyfall? I’m not sure.

DEADLINE: Well, I think he says it after every movie.

MENDES

: You’re probably right. He might say it, after every scene. It’s a daily occurrence. This is why his comments get misjudged. I’d put it this way. Daniel leaves everything on the field. Every piece of him is out there and he’s so spent when he’s finished that it’s obviously the wrong time to ask, the day after he’s finished, which is what happened. The pronouncements after the last movie were taken seriously and I then had to undo them when I agreed to make this movie. Without giving too much away, the difference here for me is, this movie draws together all four of Daniel’s movies into one final story, and he completes a journey. That wasn’t the case last time. There is a sense of completeness that wasn’t there at the end of Skyfall, and that’s what makes this feel different. It feels like there’s a rightness to it, that I have finished a journey. I’m not talking about Daniel here because Daniel may absolutely turn around six months’ time and feel his energy renewed. Or he might say just the opposite. If he is as sensible as I think he is, he needs to go away and have some time to think and do another job that’s completely different, which he’s already doing with Othello.

DEADLINE: OK, but let’s say that, just like last time, Daniel says, I’m in if Sam is in?

MENDES: By then, I’ll probably be doing something else…I’m going to get out of this by saying that, Mike. What is important is, not doing it is not a negative. It’s not me saying, “I don’t want to do this.” What it would be is me saying, “I really want to do this story.” There are other stories to tell. I’ve never felt shy of shifting genres, shifting scales, moving to a movie that’s completely unlike the one I’d done before. Until I did these two, every movie I directed was the absolutely polar opposite of the one before it. That was not random; it is deliberate attempt to not repeat myself, and to challenge myself with different stylistic challenges. That is how it is with the filmmakers I most admire, like Ang Lee and Billy Wilder. Look at Wilder, for God’s sake. Double Indemnity and Some Like it Hot and The Apartment. Ang can do Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, The Ice Storm, The Hulk, Life Of Pi and Brokeback Mountain. What a career! He has experimented in 3D, and 2D, and digital. It seems to me that there are some filmmakers who need to feel a new challenge with each film, and some who essentially make the same film or operate the same style with different subject matter. They’re equally valid.

DEADLINE: You have a reputation for being meticulous and detail-oriented. You started shooting only late last year, and that means you shot and posted a 007 spectacle in less than a year. You had a release date hanging over your head and then your star got seriously injured. What did all this pressure do to the pace of the way you usually make decisions, and even your sanity?

MENDES: That’s a very good question. It did not affect the pace at which I work, which meant that post-production was insane because I refused to compromise and cut corners while we were shooting. I was very, very fortunate in that it was the first time I’d ever worked with the editor Lee Smith, who is a genius and was able to cut alongside us as we were shooting. That meant that in the break we had to take when Daniel was off with his injury, we were able to really look at half the movie and shape it and reshape. So we were really ahead, and not behind. It was the first time ever, in any movie and even one that big, that I had a really pretty good cut three days after we wrapped. That was because of Lee and that his and my working relationship was so fluid, so good, so easy, so quick. That was massive. Without Lee, post on this movie would have been a car crash. Even then, it was still an absurdly compressed post schedule, with 16-hour days, seven days a week, no time off, no days off. But I don’t actually think it affected the movie in any way and that’s amazing. Sanity however? That remains to be seen.

DEADLINE: Was there a moment where you thought, we’re not going to make this deadline?

MENDES: We were in Mexico City, when Daniel said, “I can’t run. I can barely walk.” And he had only run about one day at that point, and I thought, “We’ve got four months to go. If you can’t run now, how are we going to do this?” He was very distressed because he was in pain, A, and B, because he thought he was letting us down. All we could say was, “Go rest. Do what you have to do to your knee and we’ll go down for a week or two and reorganize and reschedule, so that you can come back with some strength.” So there were two days there where I thought we’re never going to do this. We’re never going to make this, and we were absolutely got to the point where he could easily have called up and said, “I still can’t walk. We have to stop and we’ll pick it up again after the year, and release it the following year.” Weirdly, that created a turning point, where the opposite happened.

DEADLINE: What does that mean?

MENDES: He came back with renewed energy. He’d had a bit of a rest. He sorted out his knee temporarily, well enough to get through. And he was heroic, and for some reason the movie gods smiled and everything we tried seemed to work. Every location was great. The movie started to pick up pace again. We had some issues over the third act. We worked them out and from then until the release it felt like a downward hill rather than an upward hill. Everything up to Mexico, we were pushing boulders up a hill. It was just one of those things. The moment of greatest crisis turned out to have been the turning point.

DEADLINE: It is easy to imagine him as an I’ll-walk-it-off kind of guy.

MENDES: I think he would have done it with a broken leg, no question. He takes it so seriously. And we were very fortunate that he kept himself so incredibly physically fit. It kept this together; a less fit person would have just gone under but at that point he just made a huge physical effort and it obviously took it out of him but it was worth it.

DEADLINE: You made your second film,

Road To Perdition, with Daniel as the villain, surrounded by Paul Newman, Tom Hanks, even Jude Law’s psycho hit man. Hard to stand out. If someone had pointed to him then and said, he’s going to be the best James Bond they’ve ever had, what would you have said?

MENDES: Well, I’m on record of saying I thought they were mad to cast him in the first place as Bond. Because for me, at that point, Bond was not Daniel Craig. Bond had become something completely different and I thought, how is that going to chime? You’ve got somebody who’s real and direct, and powerful and truthful but is not…

DEADLINE: Varnished?

MENDES: Exactly. Unvarnished. And how is that going to work? And of course that proved to be the very thing that was exciting about him. You could argue, like Connery, it was the fact that they cast someone who actually was intrinsically quite different from the character. The friction that existed between who they really were and who they were playing, gave off dark energy. Connery, Scottish, working class, no direct parallel to Bond, and yet there was this energy that came off him when he played the role. Same for Daniel. So never in a million years would I have said, “You could be James Bond.” But I would have said, “You could be a movie star.” Because I felt he had the charisma and the chops to do that and I always believed in him. What I thought about Daniel was that his own worst enemy might be himself at that stage because he was always a very tightly wound, incredibly…there’s a great line about Edmund Kean, the great Shakespearean actor. Someone said it was like watching Shakespeare illuminated by flashes of lightning. I always felt that Daniel had these flashes of lightning and that it might mean an explosive movie career but I could have just seen him going along the Russell Crowe route for example, because there’s a real shortage of masculine male leading actors. And Daniel is all man. So I absolutely would have said that might have been in his future but I could never have predicted Bond nor the journey we would take together.

DEADLINE: Ridley Scott spoke to Deadline and described how he was a terrible student who’d get cuffed in the head by a teacher, because he was more interested in doodling in his notebook than whatever Napoleon was doing in the Peninsula War. He’d discover eventually that his gift was his ability to visualize and shoot scenes.

MENDES: Have you ever seen Ridley’s doodles? What he calls doodles, others call masterpieces.

DEADLINE: I confess I walked off with the ones he left behind, in our interview. I bring him up because you fast got this wunderkind label for your stage work, and then your first film wins Best Picture and earns you a Best Director Oscar. What quality did you discover inside you that made you so well suited for stage and film directing? And when did you discover it?

MENDES: Well, I was also a poor student. In England, you had these exams when you were 16, called O levels, and you had to get five O levels to get into the next grade. Otherwise you’d be held back a year. All my friends were 14 and 13 and 12 levels and I got 6, and just scraped through, and I’ve often thought if I hadn’t, I would have left school and life would have been very different. I don’t think I’m like Ridley, who is clearly a visual genius, who early on made Blade Runner. I don’t consider myself to be gifted in that way, or like a musician who could pick up an instrument and compose something on the spot. I learned to be a good storyteller and I think I do have an eye, but it’s something that has grown and emerged gradually throughout my adult life.

DEADLINE: What lit your fuse?

MENDES: I went to university, to be a journalist. I was 18 and I went around what they call Freshers’ Fair, all the stalls in the first day of university with all the different societies you can join as a student. I remember scoffing at all the drama stalls and the drama society. Bloody actors. What a waste of time. And I went instead to the student newspapers. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to write for papers. My college at Cambridge had an old lecture theater they had converted back into a theater. No one had ever done a play in it, and me and four friends decided to do one. And I said, “Well, I’ll direct it.” I liked the sound of it but I didn’t really know what it was. I never studied it. I was 18 years old. And I got into the room with them and I watched them doing the scene and it was very clear to me what they were doing wrong. So I said, “Stop. This is wrong. You should be over there. You should be over there. And you should wait to say that line,” or something like that. And I could feel all of them turning to me as if to say, “Huh. Look at you. The big guy over there with the cigar, telling us what to do. Well, we might as well try it. He seems to speak with some authority.” And they tried it and it was better. I remember feeling like…”I can do this.” That sounds totally arrogant but I did feel that way, and more to the point, I could not wait to carry on doing it. I couldn’t wait to get back into the rehearsals the following day and I was really pissed off because none of them wanted to come back. “We’ve got an essay to write. We’ve got to do this and we’ve got to do that. Can we do it next week?” No. You’ve got to do it now. We can be really good.

I still haven’t quite got over the feeling. I spent my three years at the university begging people…literally knocking on their doors, waking them up and dragging them into rehearsals. People are now paid to come into rehearsals with me and I’m paid. It still amazes me. But that was the beginning. It wasn’t a gift, just that if I had a bunch of people in a room, I knew that I could lead them toward something. And now, it’s just a question of how many people, 12 on a play or with a movie, 800. The trickier thing, and where my years in the theater helped most, is holding the whole story and rhythm in your head when you’re shooting for eight months. Knowing what you might or might not need at that given time in the movie. Because at a certain point, everyone loses contact with the narrative. If you don’t have hold of it, then no one will.

DEADLINE: Not many movie directors had the instant right-out-of-the-gate success you did on

American Beauty. It evoked comparisons to Orson Welles. In the wrong hands, the subject matter of that film could have been tawdry and lurid. You’d succeeded on the stage, but I always wondered how you process such staggering first time success, the expectations it brings and the paralysis that comes with worrying you might never get back to those heights. What was hardest to process?

MENDES: The feeling of powerlessness. If you are a sportsman and you win the Super Bowl, you win it right there and then, in front of the 60,000 people and the millions watching at home, because of human endeavor. You beat the other team. Same with the World Series or World Cup. With Oscars, you made the movie years ago. Everyone has seen it and had an opinion about it. And you’re sitting there in a room, like a complete lemon, waiting for someone else to tell you whether your life is going to change or not. That is a really peculiar situation to be in, like you say, right out of the gate. You just don’t have any control over it and you know that it’s going to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it can be an amazing, life-changing thing to win an Oscar. And it would also give me power in whatever I do next. On the other hand, it could be the absolutely worst thing that could ever happen to me because, where do I go now? It was a very peculiar experience, I won’t lie, to be sitting in a hotel room in L.A., reading a Variety headline that said something like “Mendes The Only Certainty.” And then the BBC News guy says to me, “You know, the people back home will be very disappointed if you don’t make it.” I thought, “How have I got to this situation where I am going to be a disappointment to my country, if I don’t win the Oscar for my first film?”

DEADLINE: How did you process it when you won?

MENDES: I decided quite soon after to treat it like a bank loan I was going to pay off over a number of years. I thought, I’m going to earn this Oscar, but it is going to happen over 20, 30 years of filmmaking. No sane person could process it otherwise. Mike, can you imagine me, sitting in an auditorium with David Lynch, Robert Altman, Michael Mann, Paul Thomas Anderson, Spike Jonze, and I deserve this win? It’s ridiculous. These are my heroes and there am I. Then I thought, “OK. So I’m going to treat early success in the movies in exactly the same way as I treated early success in the theater, and work my ass off to prove it was not a fluke. I’m going to earn my spurs, and I’m going to do different movies. I’ll make a gangster movie. I’ll make a war movie. I’m going to do handheld, I’m going to make family dramas and I’m going to make a big action movie.” And that’s what I’ve done. I didn’t work it all out upfront to that point, just that I was going to push, and not make the same movie again or work in the same style, or repeat myself. That’s what I did in the theater and I made some pretty bad productions in the early years, because I was pushing to see if I was any good at them or if there was some personal connection. Eventually I figured it out by trial and error. I hope it was something important in the making of me, but it was not easy at times and you feel very alone.

DEADLINE: You’ve said how important Bond was to your childhood. How do you deal with the burden of being the guy who introduces him to a new generation, particularly as your Bond is mature and not a cartoon?

MENDES

: I have a completely clear memory of seeing Live And Let Die when I was probably 10 or 11. In those days, no videos, no DVDs, no computers. So you’d go to the movies, or wait a year until it came on television the first time. I went three times, and that world, all the voodoo stuff and the dark and very weird world of adult sexuality and danger, that was unbelievably enticing and heart opening. Sartre has a great quote, that “A man’s work is nothing more or less than a slow trek to rediscover through the detours of art, the two or three great and simple images in the presence of which his heart first opened.” And I often think of that in relation to Bond in Live And Let Die and think, well, something happened to me as a young boy there.

DEADLINE: Can that kind of wonder exist today, in this world of image overload? And what pressure does it bring that it’s on you to create the same stirrings in kids that you felt?

MENDES: I love that challenge; it’s a great privilege and excitement to express myself in that way to so many kids. I just hope that I don’t let them down and there are those pressures because at the end of the day, you may make the movie you want, but this is for the audience. And you do pray and hope that everyone believes in it as much as you do, including the kids, and you have to remind yourself every day you’re working on it that for many kids it will be their first Bond movie just as Live And Let Die was my first, and like From Russia With Love or Dr. No were for others. You hope it will make kids go seek out the earlier movies, which are now so accessible to them.

DEADLINE: No pressure, Sam.

MENDES: If you don’t like pressure, Mike, you shouldn’t be a movie director.

Related stories

'Spectre' Review: It's Harder To Bond With This 007, But He's Still The Man

David Oyelowo & Daniel Craig Will Face Off In 'Othello' For New York Theatre Workshop

Daniel Craig Says He's Done With Bond; Is The Search Now On For New 007?

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter