Business 2 Community

Business 2 CommunityExpecting More From Business — Common Wealth Contributions By Business (Part 1)

Common Wealth Contributions By Business

Much to the annoyance of some past bosses, I have a habit of asking in meetings, “Why are we doing this, and what are we hoping to achieve?”

The economic turbulence of the last dozen years has led to me wondering the same thing about how we humans conduct our economic exchange. Asking the question, “what should we want to achieve in our economies, and how do we measure it?” eventually led me to the short book Betterness: Economics for Humans, by Umair Haque.

Has Business Just Become Busyness?

In his book, Haque suggests that society’s expectations have evolved for its institutions and corporations. The profit-first laissez-faire capitalist mentality of the late 20th century has become a limited way of thinking – no longer “good enough”. He shows how capitalism started as a “new economic technology” that significant improved efficiency of exchange and increased the standard of living of all people in addition to benefitting company owners. However, in the last few decades, this “raise all boats” phenomenon is showing diminishing returns. Many companies are now merely efficient organizations for capturing existing value (such as market share) for shareholders rather than creating new wealth for society in general. Consider a couple indicators that he points out:

Though patent applications have skyrocketed, patent quality has dropped. As economist Michael Heller and law scholar Lawerence Lessig have pointed out, patents are now less expressions of true intellectual wealth than tools of strategic control.

Another proxy one might employ for organizational capital is the share of profits to the financial sector versus all other sectors…the role of the financial sector is to allocate the many kinds of capital, not produce them…today’s economy rewards people most for merely allocating existing capital.

Finally Haque points out the diminishing returns of business in general to Americans in the last decades in the areas of real shareholder value, real asset returns, job destruction instead of employment growth, lack of employee fulfillment, falling household income, stagnant household net worth, and lack of trust.

Here is the larger paradox all point to: the more “business” we do, the more our human potential, our potential to enjoy an authentically good life, and our potential to create all of the many different kinds of capital seems to diminish.

People Want More from Business

While businesses focus on competition they are familiar with, they often miss disruptors. This increase in expectations by society is, itself, becoming a disruptor. Haque mentions several examples of constituencies beginning to disrupt established governments and businesses because people are seeing inherent unfairness in institutions and organizations siphoning existing value from the common wealth and transferring it to limited beneficiaries. These new kinds of disruptors are not ones you can negotiate or bargain with:

The Occupy Movement

The Arab Spring

Harvard Medical School Students self-organizing to stop professors from accepting gifts from pharmaceutical companies

Since his book was written, you can add a couple of other movements to this list:

Protests in Turkey sparked by government choosing to build a mall over one of the last public parks in Istanbul

Protests in Brazil over government spending on development for future World Cup and Olympics events while ignoring improving services to the general population.

One indicator that businesses understand that people want more from their companies and institutions is the trend among marketers to do “cause marketing”. In other words, companies are now associating their company’s brand with a cause to engender customer loyalty. The idea is that customers will choose the company’s products or services because they believe they will be supporting something bigger than just generating profits for the company – something that inspires, elevates, and betters them and the people around them.

A second indicator is the trend for publicly traded companies to provide sustainability and social responsibility reports. This is a response to socially responsible investing which seeks a return both financially and in terms of social good. Haque points to a meta-study, People and Profits?, which profiles 80 academic studies over the last 30 years of social entrepreneurship and corporate financial performance in companies. In over half these studies, a positive relationship exists, and in only 5% is there an indication of a negative impact to bottom line.

Become an “Ultracompetitor” by Developing a “Contributory Advantage”

What I like about Haque’s book is that he points out that there is significant opportunity for companies that are ambitious enough to contribute to the common wealth rather than merely profit off of it. Such companies, if they can transform to become common wealth generators, will themselves become disruptors, or as Haque calls it, part of the “ultracompetition.” It’s important to note, however, that ultracompetitors are not adversarial – offensively extracting market share from others. They’re focused on growing new wealth, and are often rewarded with additional market share as customers come to choose them.

Haque starts with a definition of wealth for a society. Just like company financial statements, he points out that merely talking about GDP growth is just talking about a company’s revenue. To get a clear idea of actual health of an economy, we also need an economy-wide wealth balance statements.

Such a common wealth balance sheet could be as depicted below. The categories are suggestions from Haque’s book. The line items are detail that I added and they aren’t anywhere near complete.

Common Wealth Balance Statement

Natural Capital

Air, water qualit

Acres / % preserved wild lands per capita

Biodiversity

Renewable resources developed / potential production

Financial capital

Available investment capital

Median household net worth

Wealth distribution

Poverty rate

Freedom to move capital

Intellectual Capital

Patents in production

Works of art, artists per capita

New industry and sector creation

Utilization of free speech

Cultural works

Human Capital

Education levels

Mental and physical health per capita

Employment rate / reemployment rate

Social Capital

Wealth in relationships

Community cohesion

Personal freedom

Community participation

Emotional Capital

Happiness levels

Satisfaction

Passion

Engagement in voting, employment, community

Organizational Capital

Ability to make and execute decisions

Social and economic mobility

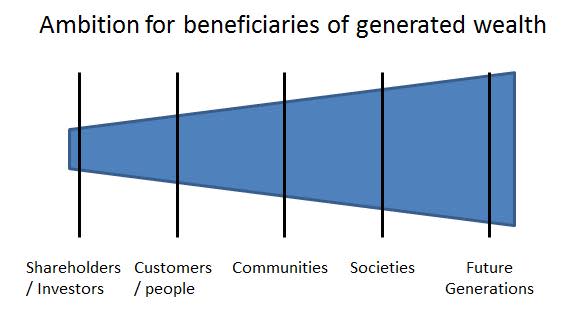

A company’s contribution to the common wealth can be rated in terms of the ambition of its impact. Note that while contributing to future generations indeed sounds impressive versus merely just its customers, feasibility and degree of impact to individuals are just as important measures. Do you significantly improve the health of your customers all the time or take a chance that you might make a tiny impact for all the children of the world. Both can be noteworthy.

Common Wealth Contributions – What Should “Better” Really Mean In Business? (Pt 1)

Rating the ambition of common wealth generation goals.

We are just getting started in figuring out how to measure common wealth. Haque points to some early projects : the Genuine Progress Indicator, the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, and the Happy Planet Index. Each of these measures suggests that the common wealth is not increasing, despite the fact that net earnings of companies, and GDP of countries is increasing. This would mean that we are burning our common wealth for the sake of income, which is getting us either no place fast.

Some Companies Already Have Contributory Advantages

Companies with an ambition to contribute to society’s common wealth would provide products and services that directly contribute in these areas of common good to their customers, localities, countries, and future generations, depending on how great the company’s ambition is.

Haque provides examples of companies, social enterprises and NGOs that have inspired loyalty from customers, donors, and populations by focusing on contributing to the common wealth. As he puts it, these entities are a new kind of innovator, a “behavior innovator.” He points out that many of them aren’t just leaders in profitability, but have rewritten the rules of profitability. Examples of this kind of thinking in companies you may know include:

Lululemon athletica whose ambition is to create components for people to live longer, healthier, and fun lives, and who offers classes, workshops, and seminars to better the human potential of their customers.

Google whose ambition is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful, and operates under constraints as “you can make money without doing evil” and “It’s best if you do one thing really, really well.”

Hannaford, a grocery retailer, whose employee’s daily intention is to “help food shoppers make healthier choices.”

Whole Foods who operates with constraints such as “We feature foods that are free of artificial preservatives, colors, flavors, sweeteners, and hydrogenated fats.”

Walmart who operates with a constraint “To reach a day where there are no dumpsters behind our stores and clubs, and no landfills containing our throwaways. We want to create zero waste.”

Pixar that operated under imperatives such as “Stories always come first”, “Technology is a means, not an end”, and “Money is not the reason we make films”.

The above examples are related to the organizing principles of those companies, and they are reflected in superior results of their operations and in the customer loyalty they enjoy. Haque also points out the above companies are far from perfect, and he also names numerous counter examples in his book.

In a follow up blog, I will test out this framework for common wealth contributions using the real life example of the company I work at: SAP, as well as discuss how this new mindset has affecting my approach to my own work.

What do you think of these ideas? How do the companies you know, work for, and buy products from stack up in this framework? Does this line point of view have merit, or are we are denying reality of markets.

Leave a comment and let us know your thoughts.

More Business articles from Business 2 Community: