Fact check: 5 key parts of Oliver Stone's 'Snowden' biopic that don't match reality

“Is it a true story?”

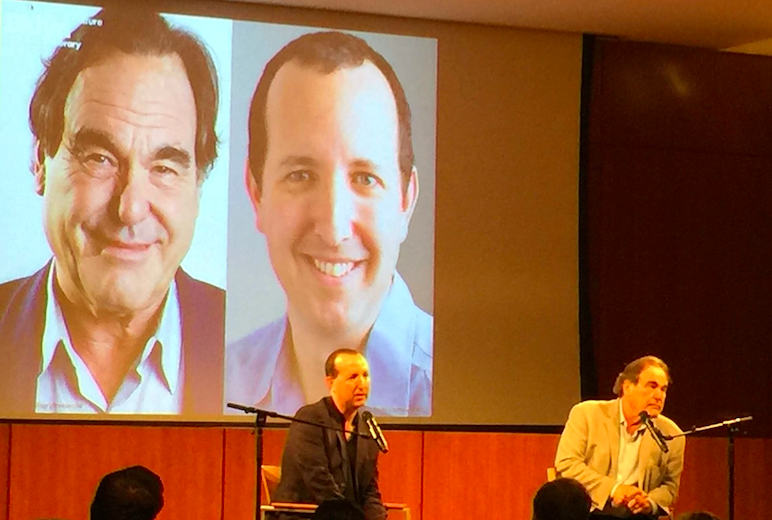

That was a question asked by Edward Snowden’s U.S. lawyer, Ben Wizner, while discussing Oliver Stone’s new biopic, “Snowden,” at the Brooklyn Public Library on Sunday. Stone answered that his film was “as close to reality as possible,” and Wizner pointed to Snowden’s own recent statement that the biopic is “as close to real as you can get.”

But as with many Stone movies that are based on real events, the director took multiple liberties with the known facts. Here are five significant inaccuracies in “Snowden.”

(Warning: Spoilers ahead.)

1) The 4-minute theft

The movie suggests one of the events that motivated Snowden to steal NSA surveillance documents and then leak them was Director of National Security James Clapper’s false testimony in which he said the NSA does “not wittingly” collect records “in any way” on American citizens. Indeed, Snowden himself has suggested this was one of his motivations. But Clapper’s testimony was in March 2013, and Snowden reportedly began stealing documents as early as April 2012.

Snowden began downloading documents related to the NSA collecting information from transoceanic fiber optic cables while working as a contractor for Dell in April of 2012, according to Reuters, which cited U.S. officials and other sources. In March 2013, Snowden got a job as a systems administrator for Booz Allen Hamilton to gain better access to documents. At some point, he built a custom Web crawler to systematically scrape specific information from NSA systems while he went about his work as a computer security expert.

The document theft in “Snowden” happens quickly: Snowden inserts an SD card into a computer, pulls up a number of folders — such as “Domestic surveillance,” “False statements” and “NSA mass surveillance projects” — and copies them onto the device. The whole sequence takes less than five minutes.

Consequently, the film’s suggestion that Snowden decided to steal documents right before he fled Hawaii for Hong Kong is clearly inaccurate. By the time Clapper testified, Snowden had already been allegedly stealing documents for months and discussing his planned leak with journalist Laura Poitras for two months.

Why this matters: Snowden’s motivations are central to his historic theft and leak. The fact that he decided to steal documents as early as April 2012 subverts the depiction that Clapper’s testimony persuaded Snowden to act.

2) ‘3 weeks’ at the Mira Hotel

[UPDATE 3/21/17: The Mira Hotel has produced records of Snowden’s stay during the May 21-June 10 time period, contradicting what hotel employees told the Wall Street Journal in June 2014.]

The film shows Snowden meeting with Poitras, as well as journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill, in early June 2013. On June 4, the phone rings in Snowden’s hotel room. Asked if he had received a call before, Snowden answers: “Not once, not in three weeks.”

The line is a minor one, but it belies what is known about Snowden’s stay in Hong Kong. Specifically, Snowden reportedly checked into the hotel just days before that phone call.

Edward Jay Epstein of the Wall Street Journal went to Hong Kong and found that Snowden didn’t check into the Mira Hotel until June 1, despite having arrived in the Chinese special-administrative region on May 20.

“Mr. Snowden would tell Mr. Greenwald on June 3 that he had been ‘holed up’ in his room at the Mira Hotel from the time of his arrival in Hong Kong,” Epstein reported. “But according to inquiries by Wall Street Journal reporter Te-Ping Chen, Mr. Snowden arrived there on June 1. I confirmed that date with the hotel’s employees. A hotel security guard told me that Mr. Snowden was not in the Mira during that late-May period and, when he did stay there, he used his own passport and credit card.”

Epstein also cited a source familiar with the Defense Intelligence Agency report on the Snowden affair in order to report that: “U.S. investigative agencies have been unable to find any credit-card charges or hotel records indicating his whereabouts” between May 20 and June 1.

Why it matters: If Snowden didn’t check into the Mira until June 1, he initially visited someone else in Hong Kong. Albert Ho, one of Snowden’s Hong Kong lawyers, referred to the unidentified person as Snowden’s “carer.” This person’s crucial role in Snowden’s escape has never been explained.

“I don’t know where he was for these 11 days,” Epstein said in an interview in August 2014. “It’s very important because if we knew where he was, then we’d know who he went to see in Hong Kong.”

3) ‘I no longer have access to any of these files’

The Guardian published the first Snowden story, revealing a top-secret program to collect records of phone calls made by Americans, on June 5, 2013. On June 9, as the leaks captivated the world, Snowden identified himself in a YouTube video. The next day, the film shows Snowden discussing the security of the stolen files with the journalists in his hotel room.

“I no longer have access to any of these files myself,” the Snowden character says after pressing a key on a laptop on June 10. “You guys have them all.”

This statement is clearly false, based on an interview Snowden gave to Lana Lam of the South China Morning Post on June 12. Snowden provided Lam with information that was withheld from the American journalists.

“I did not release them earlier because I don’t want to simply dump huge amounts of documents without regard to their content,” Snowden told Lam over encrypted chat. “I have to screen everything before releasing it to journalists.”

Snowden added that he had much more information to release.

“If I have time to go through this information, I would like to make it available to journalists in each country to make their own assessment, independent of my bias, as to whether or not the knowledge of U.S. network operations against their people should be published,” Snowden told Lam.

U.S. officials feared that Snowden had taken as many as 1.7 million classified documents from NSA systems during his work as an NSA contractor for Dell and Booz Allen Hamilton. (Exactly how much he took remains unclear.) The U.S. estimated that he gave about 200,000 documents to the American journalists Poitras and Greenwald.

Why it matters: The stolen documents allegedly include 900,000 Defense Department documents and “blueprints” detailing how the NSA functions. And Snowden alternatively told NBC that he destroyed documents “to make sure that for example the Russians can’t break my fingers.” Overall, questions remain about what happened to all of the stolen information.

4) Hiding in Hong Kong and finding asylum

The movie shows Snowden spending all of his time in Hong Kong at the Mira Hotel and then, after his name becomes public on June 10, fleeing with his lawyer to the home of a poor family. He hides there until he boards a flight to Moscow with WikiLeaks adviser Sarah Harrison.

What does film leave out? The on-the-ground work by WikiLeaks to find Snowden asylum and at least three trips the American fugitive made to the building housing the Russian consulate in Hong Kong.

As Snowden found a safe house in Hong Kong, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange sent his personal assistant and girlfriend, Sarah Harrison, to find Snowden asylum outside of China. Harrison, who was in Melbourne at the time, told Vogue that Assange called her on the morning of June 10 and dispatched her “immediately and secretly to canvass foreign embassies to see which countries might be amenable to granting Snowden asylum.”

On June 11, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s spokesman announced that the country would consider an asylum application by Snowden. And Putin, after denying knowledge of Snowden’s flight to Moscow, later admitted that Snowden “first appeared in Hong Kong and met with our diplomatic representatives.” A U.S. official told Epstein that CCTV cameras recorded Snowden entering the skyscraper housing the Russian consulate in Hong Kong three times in June.

Why it matters: The involvement of WikiLeaks and the Kremlin while Snowden hid in Hong Kong raises the prospect that Assange, who has amicable relations with Russia, linked Snowden with Russian officials while attempting to find him asylum.

“You need to find a way to Russian officials. It’s not so easy,” Russian security expert Andrei Soldatov told me in January 2014. “You cannot just knock on the door and say, ‘I am an NSA whistleblower and I want contact with the Russians.’ So I think that some contacts were provided by Assange. I strongly suspect that there should be some connection.”

5) ‘Ask the State Department’

Stone’s film repeats the argument that the U.S. revoked Snowden passport on June 23, 2013, while he was on the flight from Hong Kong to Moscow, thereby stranding him in Russia as soon as he landed.

“When people say ‘Why are you in Russia?’ I say, ‘Ask the State Department,'” Snowden’s character says, echoing what Snowden has said in real life.

However, according to the State Department, the U.S. government revoked Snowden’s passport the day before he left Hong Kong. “Consul General-Hong Kong confirmed Hong Kong authorities were notified that Mr. Snowden’s passport was revoked June 22,” the State Department’s senior watch officer told officials.

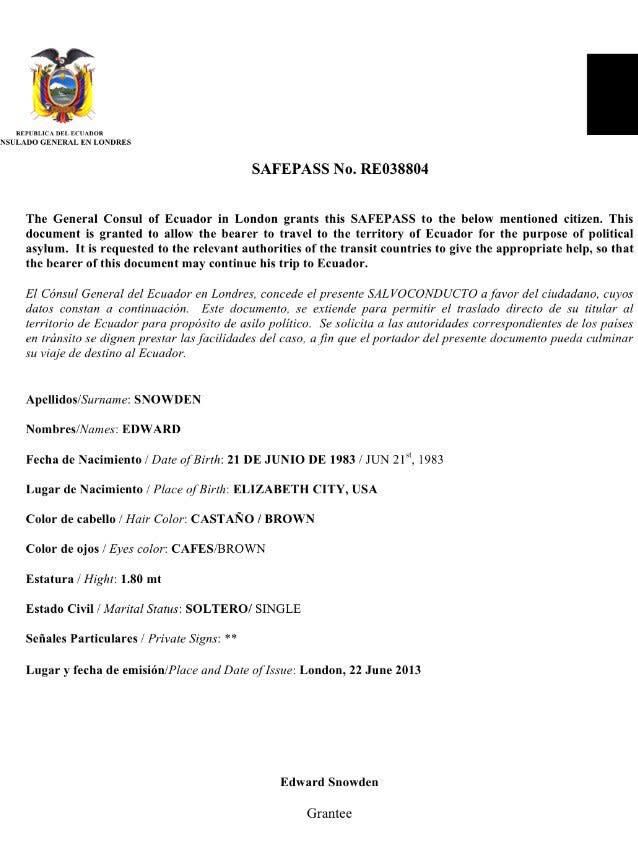

Also on June 22, Assange obtained an unsigned “special refugee travel document” from the Ecuadorian lawyer in London that gave Snowden a semblance of travel papers while Beijing facilitated his exit. WikiLeaks later reiterated that Assange obtained the Ecuadorian document specifically so that Snowden could leave Hong Kong and travel to Ecuador via Russia. However, Ecuador’s president subsequently said that the travel pass was “completely invalid,” adding that Snowden was “under the care of the Russian authorities.”

Why it matters: The notion that the U.S. stranded Snowden in Russia is crucial to Snowden and his supporters arguing that he would otherwise have traveled to Latin America. The notion that Snowden is stuck in Russia largely because of Assange, who paid for Snowden’s plane tickets, lodging and legal counsel in Hong Kong while advising him to seek asylum in Russia, subverts the Latin America argument.

So what?

These discrepancies wouldn’t matter as much if Stone and Snowden said that the movie simplifies and fictionalizes certain events. But with the director and the primary subject swearing by the accuracy of the film, these editorial choices take on more meaning. After all, Snowden has been charged with theft of government property and two violations of the U.S. Espionage Act for disclosing classified communications.

Snowden’s supporters hope that the film will galvanize support for a presidential pardon. At the screening, Wizner announced that the ACLU and other organizations are launching a formal campaign this week — along with the website pardonSnowden.org — that will attempt to persuade President Obama to pardon Snowden before he leaves office. Stone’s film is being used as part of that campaign.

“I think Oliver will do more for Snowden in two hours than his lawyers have been able to do in three years,” Wizner told Vice reporter Jason Koebler at the Brooklyn Public Library.

“Snowden” is very much the story that Edward Snowden would like to be told. Snowden even makes a cameo at the end of the film, which serves as his seal of approval. But Stone’s biopic curbs some of the unflattering aspects of Snowden’s heist and asylum, and viewers should keep the full context in mind.

Read also: In exile, Edward Snowden rakes in speaking fees while hoping for a pardon