Fidel’s Pyrrhic victory: Standing up to the U.S. at a high price for Cubans

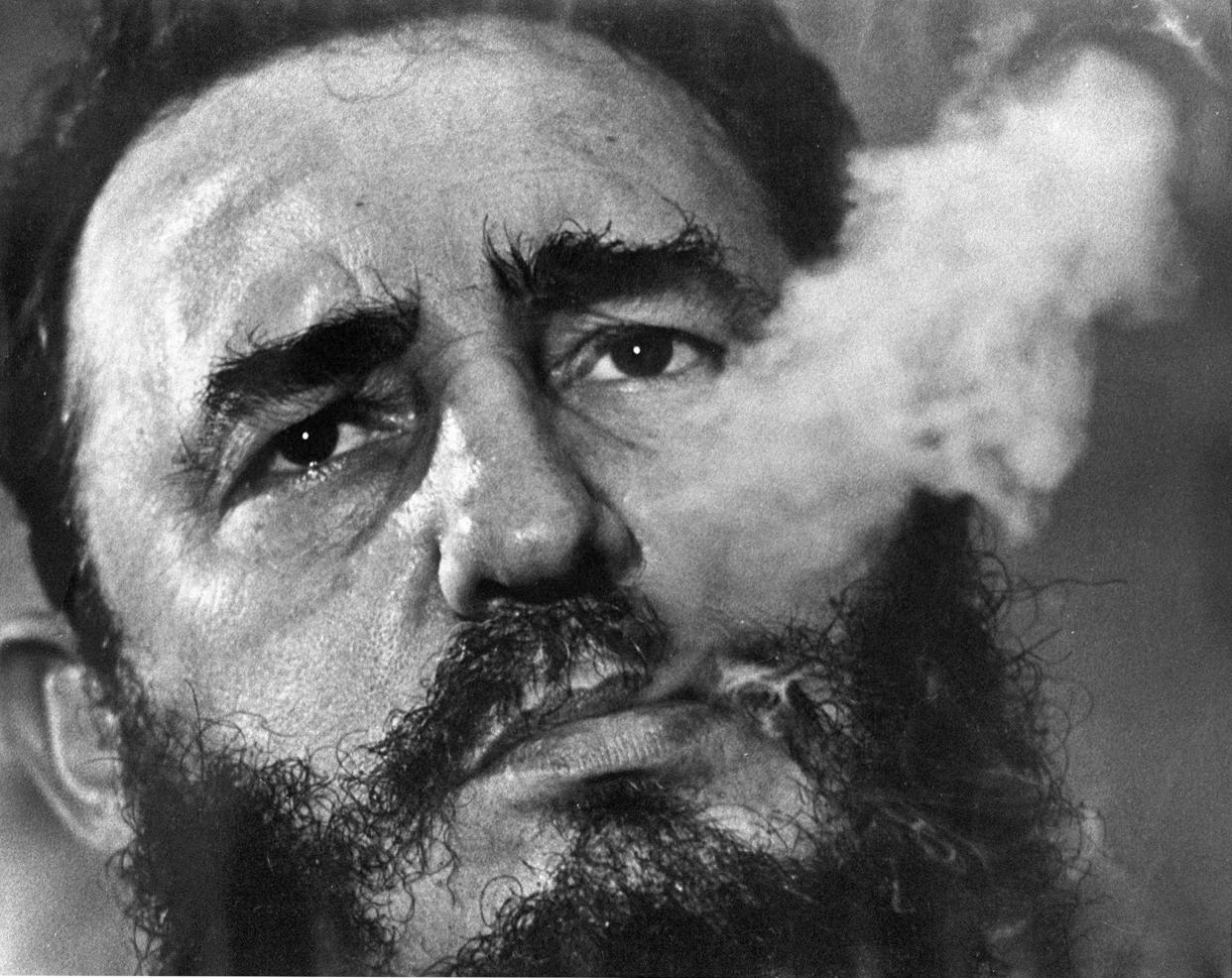

He wins. Fidel Castro has died, reportedly at the age of 90, with his boots on, stubborn, independent, aloof to the last.

Of the many things that can be said of this voluble giant of the 20th century, who died almost silently in the 21st, it must be conceded that he won his most crucial battle. The Cuban Revolution may have failed at almost everything it tried, creating a half-century of decline, isolation and deprivation, but in one way Fidel Castro triumphed.

After the great reforms of the 1960s and the international adventures of the 1970s and all the economic promises of later decades fell away, he was left with one final justification. He withstood America. For as long as Castro lived, and for the first time in history, a Cuban stood up to the powerful outsiders who coveted the island.

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was officially born in 1926, although Castro himself admitted that was inaccurate — a talented southpaw pitcher in his youth, he was probably made younger on paper by one year. He grew up in Cuba’s sugar belt in a house with a thatched roof, yet was privileged by a wealthy father, and honed his searing intelligence and ambition at Jesuit schools. (By the age of 13, he told classmates he would be president of Cuba.) He married into one of the country’s most important political clans but never forgot or forgave the imbalance between rich and poor, rural and urban, white and black, American and Cuban.

Slideshow: Fidel Castro dies at 90: His life in photos >>>

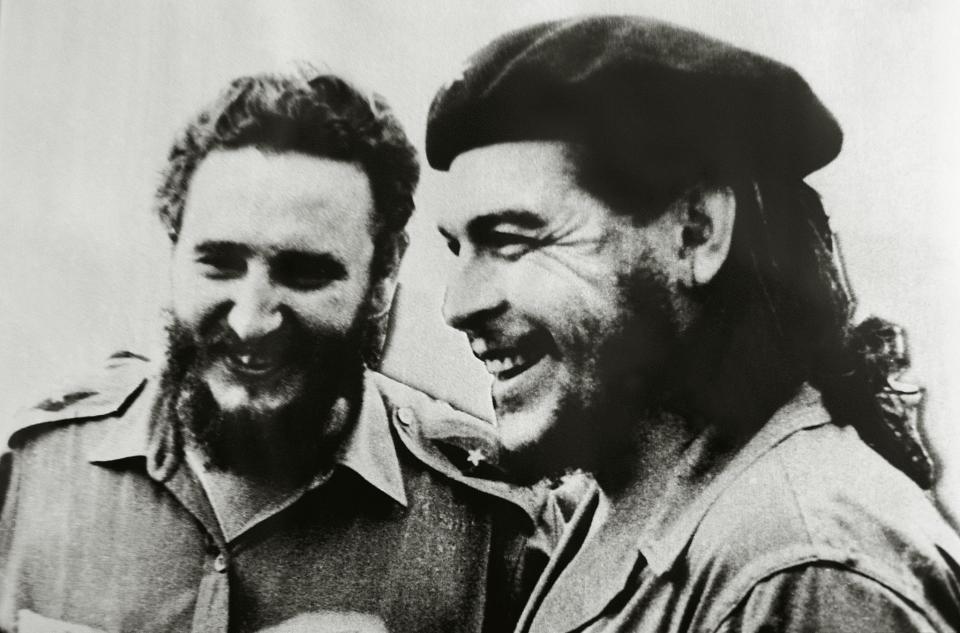

Of the courageous guerrilla war Fidel fought and won, enough has been said. The desperate victories and heroic stands at the side of Che Guevara and younger brother Raúl are best captured in the era’s iconic photography. Bookshelves have collapsed from the weight of tomes retelling the classic moments of the war — from the invasion in a leaky yacht and initial defeat to the gradual populist uprising that drove the corrupt, American-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista from power and carried Fidel, then a lawyer in his early 30s, to Havana on a wave of cheers. The discovery that a small, determined band of guerrillas could overthrow a government set off a wave of panic in Washington and led to U.S. assassination schemes and the disastrous invasion at the Bay of Pigs. Castro’s success — and endurance — gave hope to disenfranchised people around the world and emboldened a wave of bloody and failed imitators.

History will not absolve Fidel Castro. He swept into power promising a return to constitutional rule and free, open elections. The slogans were benign at first. “Bread without terror.” “Neither dictatorship from the right nor dictatorship from the left.” “A revolution of the poor and for the poor.” But eventually the police state took over, all businesses were shuttered by 1968, and by 1970 an era of Stalinist show trials had begun.

Fidel proved more loyal to the Russian way than Russia’s own leaders, and after the Cold War ended in 1992 he soldiered on, alone. Carlos Franqui, an intimate, said that beneath his blinding charisma, Fidel was “ultimately a clear-eyed realist about power.” Where others fell, Fidel marched on, the world’s longest-running dictator, a shape shifter content only with one goal beyond all others, keeping himself in office as a way of keeping America out of Cuba. Never tempted by wealth or distracted by his own vanities, he proved to be a man without a price.

I managed to see Fidel Castro on five occasions, without ever speaking to him. He was there at Che Guevara’s funeral in 1997, blasting a long speech across the huge crowds assembled outside Santa Clara; in Havana his elaborate morning motorcade once roared past me; on another occasion, Fidel appeared riding slowly through Old Havana in a ZiL limousine, alone but for a single aide and chased by cheering boys on bicycles. My closest and most sustained examination of the man — known variously as the Bearded One, the Horse or just Him — was at a long, pointless rally where I edged within 40 feet of Cuba’s supreme authority.

There, with trembling hands, he struggled to read his own speech and then had to be helped down from the podium by attendants hiding his obvious infirmity. That moment of physical vulnerability occurred not recently but back in 1999, proving that the Maximum Leader was weak in body long ago but sustained by willpower through more than another decade. Ceding power to his brother after being struck down by diverticulitis in 2006, he continued to publish hundreds of rambling commentaries on geopolitics and to make rare appearances, such as touring an art gallery in 2013, when he arrived in a wheelchair but managed to utter the familiar slogans.

On Dec. 17, 2014, President Obama overturned 54 years of U.S. policy by sending an ambassador to Havana. Some called it a victory for Fidel, but Castro himself needed months to react, endorsing the deal in a meek and stiff letter. Perhaps he knew his was a Pyrrhic victory. Perhaps he knew that change will finally bring the Americans he always held off.

He departs just in time. The end of overt American hostility toward Cuba will diminish the island’s role in the world, and the revolution’s role in Cuba. With his death, the question in Cuba is no longer will there be change, but how much, and when. When the pomp of politics and the orgy of transnational mourning are long over, Cubans will be left to face a wave of uncertainty. That includes the fate of Fidelismo without Fidel.

The Cuban system was more than just two brothers named Castro. Seven percent of Cubans are members of the Communist Party. Innumerable others have lashed themselves to the mast of the revolution, and every single person on the island is touched by that system. Part of Fidel’s legacy will play out in the dismantling of his economic chokehold on daily life, a process grudgingly begun by Raúl Castro. The system of justice, built to guarantee unfair outcomes, will have to be reformed. More profoundly, society will need decades to undo what Czeslaw Milosz called “the captive mind,” the net of unspoken rules and invisible fears that have shaped Cuban life. Fidel died just in time, before that tide floods the wreck he left behind. As a corpse, a symbol, a colossus who bestrode his times, Fidel Castro will endure long after his works are gone.

Slideshow: Reaction to the death of Fidel Castro >>>

The only certainty about the future is that no one will ever fill the Comandante’s big boots. Raúl Castro will continue his own reign for now, but there will never be a replacement for his older brother, the man known worldwide as Fidel, or “Loyal.”

As the human rights dissident Elizardo Sanchez once told me in Havana: “You can’t make an elephant out of 100 rabbits.”

_____

Patrick Symmes is a journalist and the author of The Boys from Dolores: Fidel Castro’s Schoolmates from Revolution to Exile.