BP Goes Deeper Into Gulf of Mexico, After Triumphs and Tragedy

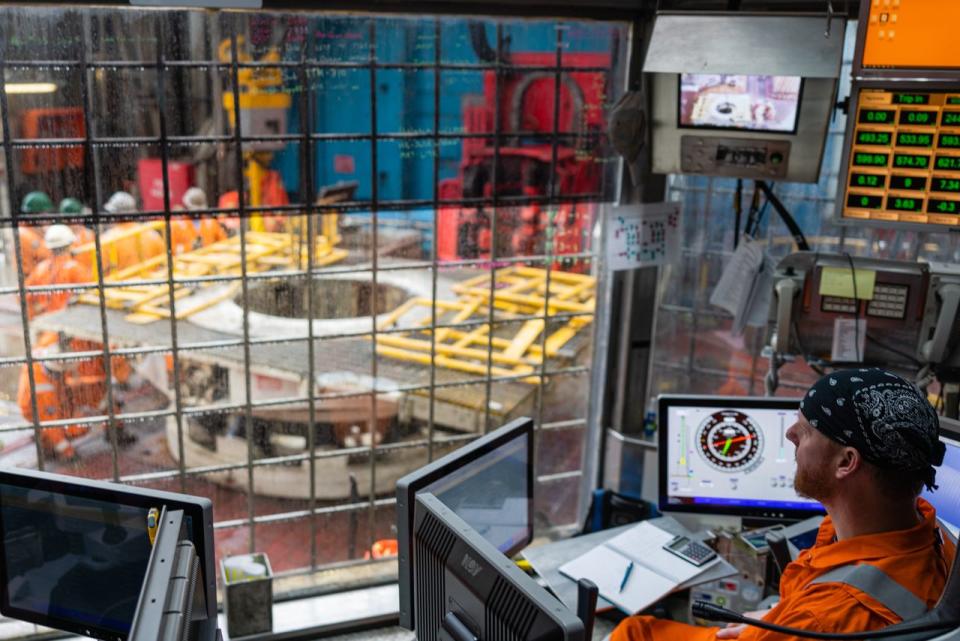

THUNDER HORSE OIL PLATFORM—This hulking production base 150 miles offshore from New Orleans has long embodied BP’s outsize ambitions in the Gulf of Mexico and also reflected its recurring setbacks.

Most Read from The Wall Street Journal

Tesla Is Pulling Back From EV Charging, and People Are Freaking Out

BlackRock’s Plan for Your Retirement: A 401(k) With a Monthly Check

Ex-Pioneer CEO Barred From Exxon Board for Megadeal to Close

Fed Says Inflation Progress Has Stalled and Extends Wait-and-See Rate Stance

Stretching roughly three football fields and pumping crude from more than a mile below the water’s surface, Thunder Horse in 2005 was found listing so precariously that it appeared in danger of sinking.

Once it got roaring in 2008, three years behind schedule, it helped BP cement its position as one of the Gulf’s leading producers, capable of some of the industry’s biggest technical marvels.

Then in 2010, the Deepwater Horizon explosion caused the biggest offshore oil spill in U.S. history, costing the British company more than $60 billion and years of political and reputational damage.

Now three chief executives and 14 years later, BP is again betting big on the Gulf.

Thunder Horse is entrenched as one of the company’s steadiest producers, and a new production platform, called Argos, went online last year. At about one-third of the size, Argos links to subsea wells and has the capacity to produce more than half as much oil—roughly 140,000 barrels a day. BP, which will report earnings next week, has set its sights on harder-to-reach deposits in the Gulf, requiring drilling techniques to cope with more-intense pressures and higher temperatures.

In March, new CEO Murray Auchincloss was asked on stage at a Houston energy conference what business he’s most excited about. His answer: the Gulf of Mexico.

More specifically, Auchincloss called out the Paleogene, a geological layer dating back as far as 60-plus million years and where BP first discovered oil more than a decade ago. The company plans to decide whether to go forward with big projects there either later this year or next. BP says it could gain access to some 9 billion barrels of untapped oil—a massive supply.

“I think we stand the chance to open up the next great basin in the world, which is the Paleogene here in our backyard in the United States,” Auchincloss said.

No oil-and-gas supermajor has more riding on these Gulf of Mexico waters than BP, investors and industry participants say. BP is the smallest of the supermajor pack, soon to be further dwarfed as U.S. rivals Exxon Mobil and Chevron seek to close recent megadeals, and lagging behind London-based rival Shell in size and share performance.

Deep-water projects are among the industry’s biggest plays at the moment. Shell is active in the white-hot Namibia discovery, while Exxon is enjoying blockbuster production out of Guyana. Shell and Chevron also have their eyes on Paleogene oil finds in the Gulf of Mexico.

BP, which pulled back from frontier exploration in favor of its green-energy pivot in recent years under former Chief Executive Bernard Looney, isn’t involved in those big new discoveries. As a result, its Gulf of Mexico business remains the core of its deep water ambitions.

“In a resource industry, resources matter, so this could be seen as a relative disadvantage,” said RBC Capital Markets analyst Biraj Borkhataria.

Still, he expects BP to tie new Gulf projects into its existing infrastructure—an incumbent advantage—and make smaller upstream acquisitions while boosting its onshore U.S. natural-gas production.

“They’ve been one of the most successful operators” in the Gulf, said Lysle Brinker, a senior upstream oil and gas analyst with S&P Global Commodity Insights, “except for that massive mistake.”

BP has also been the focus of persistent speculation about its vulnerability as a takeover target. Some analysts and investors think it is only a matter of time before Europe’s biggest oil-and-gas companies consolidate, either through outright mergers or a combination of joint ventures and spinoffs of core businesses with other U.S. or European companies or government-backed players in the Middle East.

BP has said it’s confident its strategy is bearing fruit now and will continue to do so.

BP’s existing Gulf of Mexico footprint and prospects are a prime asset for the company, and give it room to grow there, but the clock is ticking as the world transitions to other fuels—even if the timetable is uncertain.

“You’re trying to find as much as you can by the end of this decade and develop it, hopefully economically, within the first five years or so of the next decade,” Brinker said. “Because if you don’t, who knows?”

BP’s public embrace of the Gulf is a component in the company’s shift back toward its oil-and-gas roots, which started last year under Looney. In a surprise move, he stepped down last September over undisclosed details of work relationships.

Auchincloss, the former finance chief, stepped into the role permanently in January and pushed the company further back to fossil fuels, which currently produce higher returns than many alternative energy sources such as wind and solar.

In its bid to attract more U.S. shareholders, BP is under pressure to keep cash flowing through buybacks and dividends. Some investors, including a small but vocal London-based activist fund called Bluebell Capital Partners, want less spending on green energy and more on fossil fuels.

BP under Auchincloss has said it has the capacity to increase oil production by 2% to 3% through 2027.

He told investors in February that the company has the potential to move forward with the Paleogene projects, called Kaskida and Tiber, as well as expansion projects in Brazil, Canada and the Middle East.

He added that if enough of those projects pan out, “then I think we can do better than that 2% to 3%.”

But the profit margins have to be right, he said. “I’m going to be super-focused on returns.”

Paleogene oil costs more to bring up, says Mfon Usoro, senior energy analyst with research firm Wood Mackenzie. An ultra-high-pressure barrel will require capital investment of $13 to $15, compared with $6 to $9 for conventional Gulf of Mexico operations, Usoro says.

But aside from costs, BP and other Gulf producers also cite the less-intensive carbon emissions of oil from the basin, which ties into companies’ pledges to reduce emissions.

BP is finding new ways to cut costs, avoid downtime and improve safety in the Gulf of Mexico, Auchincloss said in a February interview. The company is testing out artificial intelligence that can predict equipment failures, by sending masses of data back to central engineering nerve centers in Houston and near London.

“Gen AI can sort it, it can structure it, can communicate it back to the engineers and scientists much faster than humans,” he said.

BP has focused on smaller, more-efficient offshore platforms, linking to and replicating what’s already in the water where possible to cut costs and time to production.

From its original design to completion over more than a decade, BP reduced Argos’s costs about 60%, Starlee Sykes, BP’s then-head of Gulf of Mexico and Canada deep-water operations, said in an interview last year when the platform started production. Sykes now runs BP’s biogas business, Archaea Energy.

“I don’t think you’ll see many more Argoses or Thunder Horses,” Sykes said in an earlier interview aboard Thunder Horse, which has living quarters for around 300 people. “These are giant platforms.”

Write to Jenny Strasburg at jenny.strasburg@wsj.com