Fisherman's return stirs mixed emotions in Korean village

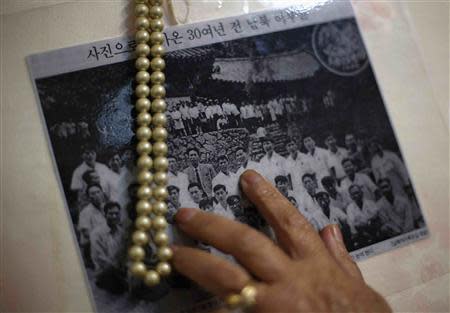

By Ju-min Park NONGSO, South Korea (Reuters) - The recent return of a South Korean fisherman abducted by North Korea more than 40 years ago has reopened wounds in a small island village that lost 17 other men in a Cold War conflict that still simmers today. Jeon Wook-pyo, who reappeared in South Korea in September after escaping from the North through China, has since paid a brief visit to Nongso - a remote outpost of around 170 people on the southern island of Geoje, about five hours drive from Seoul - but he won't be settling back there. "It wasn't a nice feeling that he reminded me of my husband. There was nothing to feel good about," said 82-year-old Ok Chul-soon, whose husband skippered one of two fishing boats that were seized with all hands, including Jeon, by North Korean patrol boats near disputed waters in December 1972. She acknowledged Jeon's return was welcome, but said she was too upset to stay throughout his visit, adding they would meet privately at some time so she could ask for news of her husband. Seoul says 516 South Koreans, mostly fishermen, remain in the North after a spate of abductions following the 1950-53 Korean War - the two sides are technically still at war as no peace treaty was ever signed. Critics say the South Korean government has abandoned those held in the North and has stigmatized their families in the South, painting them as suspected subversives with ties to North Korean spies. "The South Korean government has no interest in abductees," said Choi Wook-il, another fishermen who was snatched by the North in 1974, but who escaped in 2007. "While it sent those 63 North Koreans back, they could have traded them with South Koreans in the North," he told Reuters, referring to the return to Pyongyang, to a hero's welcome, of more than five dozen North Korean prisoners during a thaw between the two Koreas in 2000. Choi said the fishermen lived under heavy security and were subject to indoctrination with North Korea's Juche ideology. "Security agents came to my house and slept there. They followed me to the mountains, fields and market," said Choi, who was forced to work on a collective farm for 30 years, and shared a room with Jeon for three months in the late 1980s. Those abducted were used by North Korea for propaganda purposes or intelligence gathering, according to the testimony of those who have made it back to the South. Pyongyang insists anyone in the North is there voluntarily. South Korea's Ministry of Unification, which handles ties with the North, says the return of abductees is a "top priority". Critics, however, say Seoul avoids confronting the North over the issue as it doesn't want to jeopardize its policy of engagement with Pyongyang. THOSE LEFT BEHIND Fishermen from both North and South are frequently caught in disputed waters due to bad weather and a blurred sea border. Most are returned after a few weeks, but for those held in North Korea for decades, the only way out is across the armed border with China, where they risk being caught and sent back by Beijing. Nine fishermen have escaped from the North since 1998. For the latest of those, Jeon, now 68 and going through a re-education program at a government facility, it would be too "awkward" to return permanently to the tight-knit community of Nongso, said his younger brother Sung-pyo. There, the wives, sisters and mothers of those still held in the North have only fading black and white photographs of their missing menfolk. Desperate for any news, the women borrowed money to hire shamans - a widespread practice in South Korea even today - for any clues as to the fate of the fishermen. "One day, a shaman received the spirit of my dead father-in-law and he said my husband would never come back even if I did this ritual thousands of times," said 82-year-old Kim Jeom-sun, the wife of one of those abducted. During the North-South rapprochement after 2000, Ok Chul-soon applied to join a series of family reunions at a North Korean mountain resort only to receive a Red Cross letter in 2005 that simply said: "Dead". Two years later, Kim's sister-in-law, the wife of another of the village's missing fishermen, took her own life by drinking herbicide after North Korea, again through the Red Cross, said he had died. The villagers' grief has not been helped by successive South Korean governments, with the wives and children of those taken North treated as Communist sympathizers. Police maintained a close eye on the villagers following the abductions, and blocked access to jobs in public offices. "Other kids told my children: 'You can't do anything because your father's a commie'," said Kim, a mother of five. "They cried every day." (Editing by David Chance and Ian Geoghegan)