Hearing Aids Can Serve a Second Purpose As Wireless Speakers

"Never in my audiology career has something so simple helped so many people at so little cost."

"I can't stop smiling. . . . I could understand every word. . . . What an overwhelming experience."

"I am not exaggerating when I tell you that at EVERY [theatrical] performance we get big thank you's. We have subscribers who are returning and telling their friends."

These reports--from an audiologist, a person with hearing loss, and the business manager of an 882-seat Chicago theatre--aptly describe my response when first experiencing the hearing assistance technology to which they each refer. As I sat, unable to understand the words reverberating off the ancient stone walls of Scotland's Iona Abbey, my wife noticed a hearing assistance sign with a "T" and nudged me to turn on the "telecoils" in my new aids. The instant result was a stunningly clear voice, speaking from the center of my head. I was on the verge of tears.

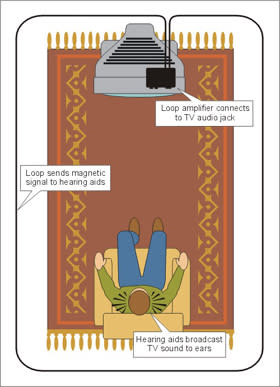

In our subsequent UK sojourns, I have experienced the spread of this "hearing loop" technology--to auditoriums, churches and cathedrals, and to tens of thousands of transient venues, including ticket and post office windows, and all London taxis. Although specific applications need professional design, the gist of the technology is simple: an amplifier picks up sound from a PA system and transforms it into a magnetic signal sent by a wire loop surrounding an audience. The telecoil--an inexpensive magnetic sensor in most of today's new hearing aids and all new cochlear implants--receives this signal, enabling the hearing instrument to become an in-the-ear speaker that broadcasts sound appropriate to each user's needs. And I bet you didn't know this: all U.S. landline phones, and select mobile phones (including my new iPhone5), also are "hearing aid compatible." That means they can similarly transmit improved sound via magnetic communication with telecoil-equipped hearing instruments.

Back home, I installed hearing loops in my home and office. Voila!, my TV and phone now broadcast wonderfully clear sound through my aids (and binaural phone listening is vastly superior to one-eared listening).

Other modern wireless technologies also connect hearing aid wearers to their TVs and phones. When connected to a TV or stereo, a transmitter can "stream" audio directly to one's hearing aids. When synced with one's phone, conversation can be broadcast to both hearing aids. Bluetooth-enabled hearing aids can receive sound from a host of Bluetooth devices, including phone and computer.

So, people often wonder, might Bluetooth or other streaming wireless technologies enable assistive listening in public venues--and without the expense of a running a loop wire?

Alas, each hearing aid company offers a different proprietary wireless technology. The one universal wireless receiver--which anyone can use, no matter what their hearing aid brand or what country they are in--is the humble telecoil (a part that costs hearing aid companies about $2). Moreover, unlike Bluetooth's battery-sucking demands, the telecoil requires zero power. With today's popular "open-fitting" hearing aids, a person may hear both immediate sound from a TV and slightly delayed Bluetooth sound, creating an annoying echo. And unlike Bluetooth and other wireless technologies that serve only small areas, hearing loops work in places both small and big.

Indeed, the accelerating move to hearing loops in the USA--sparked by local and national hearing loss associations and now supported by a new cottage industry of hearing loop vendors and installers--has led to thousands of newly looped venues. Some venues are small, such as New York City's 450 subway booths and all its future taxis. Some are bigger, such as auditoriums and worship places. And some are huge, such as airports and Michigan State University's basketball arena.

Are hearing loops the final word in assistive listening? Likely not. But the challenge for hearing technologists is to make any alternative technology similarly

simple for people of all ages to operate (without needing to pair and charge special equipment),

affordable, without adding to the cost of already-expensive hearing instruments,

available with nearly all hearing instruments,

energy efficient,

scalable, with applications in public spaces both small and vast, and

universal, with the same signal serving everyone, no matter their location or hearing instrument manufacturer.

Given a future with a universal wireless receiver (for now, a telecoil) in virtually every hearing instrument, and given the continuing spread of hearing aid compatible assistive listening, we can envision a better future for Americans with hearing loss--a future in which hearing aids will serve as customized, wireless speakers in all sorts of public venues. That, methinks, would be a future where doubly useful hearing aids for challenged ears would be as commonplace as glasses for challenged eyes.

Follow Scientific American on Twitter @SciAm and @SciamBlogs. Visit ScientificAmerican.com for the latest in science, health and technology news.

© 2013 ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved.