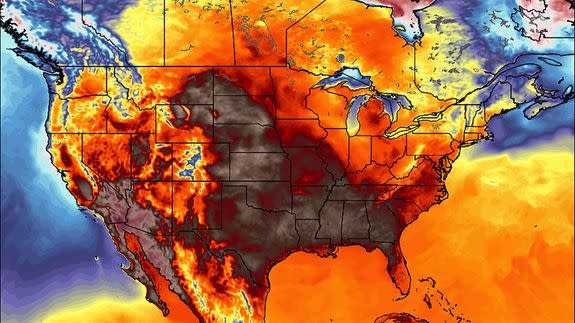

Heat dome has tens of millions sweating from Minneapolis to Mississippi

A well-advertised, intense and long-lasting heat wave is gearing up across the middle of the U.S. on Monday, and is not forecast to ebb until at least a week from now.

Although the heat may not topple many records, the combination of temperatures running between 15 and 25 degrees Fahrenheit above normal along with high humidity will make this heat event a particularly dangerous one for public health.

SEE ALSO: A massive heat wave is poised to envelop the U.S. from coast to coast next week

The heat plus humidity will send heat indexes soaring across the Plains, Upper Midwest, and mid-South, among other areas. The National Weather Service in Minneapolis, for example, has issued an excessive heat watch, warning of heat indexes reaching 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

"100 degrees in the metro area? I wouldn't rule it out. The last time MSP hit 100F was July 6, 2012 (102F)," wrote Minneapolis area meteorologist Paul Douglas on his blog.

As of Monday morning, at least 14 states had some type of extreme heat-related weather alert in place, from Louisiana to Minnesota. High temperatures in some areas will be well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, or 37.8 degrees Celsius, with heat indexes — which corresponds to how hot the air will feel to the human body — even higher than that.

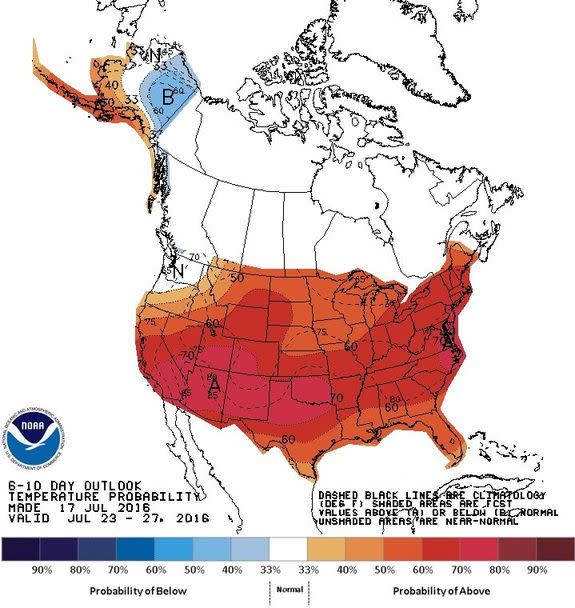

Image: NOAA/CPC

Some of the cities that will be hardest hit include Dallas, Chicago, Oklahoma City, Kansas City, St. Louis, Des Moines and Minneapolis.

Computer models have been strongly hinting at this heat wave for more than a week, and Mashable first alerted readers to it on July 13. Since that time, it's become more clear that this will not be a record-shattering event, but will nonetheless poses major risks to public health.

Prolonged exposure to heat and humidity can cause illnesses including heat stroke, and more people die each year in the U.S. from heat than from extreme cold.

Strong high pressure area won't budge

The culprit for the sultry weather is an unusually intense and expansive area of high pressure, also referred to as a "heat dome," that is parking itself over the South Central U.S.

The clockwise circulation of air around this high is dragging moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and pumping it northward, all the way to Canada, which is resulting in the high humidity levels.

In addition, evapotranspiration from crops in agricultural states such as Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa and Minnesota is also adding to the moisture content of the atmosphere.

The high pressure area itself will be strong enough to put it on a list of strongest such weather systems observed in that part of the country.

Image: NWS

Meteorologists often look to a metric known as geopotential height to gauge the intensity or unusualness of a heat dome like this. Geopotential height measures the elevation of an air pressure surface.

Hot air masses expand, and elevate pressure surfaces, while cold air masses are more dense and compact, which lowers them.

According to the National Weather Service in Minneapolis, the height of the 500 millibar pressure level may be near 6,000 meters, "which is very rare and considered an extreme event."

Citing computer model data as of Sunday morning, the Weather Service stated: "...This is expected to be the hottest atmosphere for this time of year compared to 1985-2012! As a result, this may be one of the worst heat waves in the last few decades."

Excessive heat will grip the middle of the country through the weekend, at which point computer model projections show that the heat dome will slide southwestward.

This could yield a heat event in California, Arizona and New Mexico next weekend, while the rest of the country cools off.

Climate change links

While a heat wave in mid-July somewhere in the country is a typical occurrence, extreme, long-lasting heat waves that come with high humidity are a hallmark of global warming.

As average temperatures increase around the world, there is a higher probability of extreme heat events, and this has already been observed in the U.S. and other countries.

A study published in 2015 in the journal Nature Climate Change found that the probability of 1-in-1,000-day hot extremes over land is already about five times higher than it was in pre-industrial times, when global average surface temperatures were lower.

To put it another way, the study found that about 75% of "those moderate hot extremes are attributable to warming."

The study, along with many others, found that the probability of hot extremes is likely to increase significantly as global warming continues.

Another study, published in February in the journal Climatic Change, found that severe heat waves that typically occur once every 20 years could become annual events across the majority of the world's land areas by 2075, depending on greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels.

Some reports have even raised concerns that amplified heat waves could reduce economic productivity in entire regions of the world, such as Southeast Asia, within the next few decades.