Insight: U.S. farm kids lavish shampoos and drugs on their prize cattle

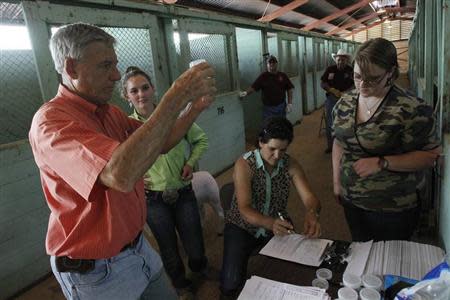

By Lisa Baertlein and P.J. Huffstutter DALLAS (Reuters) - For more than a century, ranchers and their kids have paraded cattle around the dusty show ring at the State Fair of Texas in Dallas, in a rite of passage that is part farm economics, part rural theater. Today, with U.S. auction prices for champion cattle topping $300,000 a head and hefty scholarship checks for winners at stake, the competitive pressures are intense. It's no wonder animals with names like Beast or Chappie get the farm version of luxury spa pampering - shelter from summer heat, baths with pricey shampoos and careful coiffing with electric razors. Many also get muscle-building livestock drugs added into animal feed. While performance-boosting drugs are banned today in most human sports competitions, Zilmax and other drugs of a type called beta-agonists are federally approved and generally allowed on the livestock-show circuit. For many contestants the secret weapon of choice is Zilmax, a controversial feed additive sold by Merck & Co. Zilmax-based feeds can give show kids an edge in the headline competition for market-ready steers and heifers, say show sponsors and competitors. They add thicker meat where judges like it most, between the 12th and 13th ribs, where rib-eye steaks come from. Merck temporarily suspended Zilmax sales in the United States and Canada in August, soon after the largest U.S. meat processor, Tyson Foods Inc, stopped accepting Zilmax-fed cattle for slaughter over animal welfare concerns. After Merck last week said it was preparing to return Zilmax to the market, food giant Cargill Inc declared it would bar Zilmax-fed animals from its supply chain until it was "100 percent confident" those issues are resolved. But in cattle shows at state and county fairs across the farm belt, Zilmax remains popular. Despite the halt in sales of Merck's zilpaterol - Zilmax is the trade name - existing stockpiles of Zilmax-based show feeds circulated at fairs this fall. So, too, did products made with Optaflexx, a rival drug by Eli Lilly & Co.'s Elanco Animal Health group that is based on ractopamine, also a beta-agonist. Ractopamine has not been tied to the animal welfare issues seen in cattle this year. "If it's legal, you use all of your options," said Justana Tate, 17, a Texas state fair competitor, her championship belt buckle gleaming as she stroked her snorting steer to calm him. Tate is a Zilmax fan. "I think it's a fabulous product," she said. For drug giant Merck, the show-feed market is a tiny slice of Zilmax's U.S. sales, roughly $160 million last year. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers Zilmax safe for animals and humans, though regulators say it requires labels warning people not to inhale the drug or handle it without gloves. Zilpaterol can cause dizziness and shortness of breath when inhaled and cause rashes upon contact with bare skin, according to Merck and the FDA. While the drugs remain popular with contestants, some show organizers are cracking down by testing for zilpaterol, the active ingredient in Zilmax. The organizers say they are taking their cues from the FDA, which has approved zilpaterol for use in steers and heifers slated for slaughter but bars it for use in breeding cattle and dairy cows as well as goats, pigs, sheep and horses. MUSCLE-BUILDING STAPLE Many of the fresh-faced kids who compete at cattle shows have seen beta-agonists on their family farms or feedlots. Full-strength Zilmax, when added to feed weeks before slaughter, can add about 30 pounds of muscle to the average 1,300-pound steer. When those children begin competing, some reach for medicated show feeds, which are readily available at rural feed stores and via the Internet, say competitors and show organizers. Merck does not make show feeds. Instead, feed mills blend the company's Zilmax with protein, fat, fiber or other products, and then market the mix under trade names like Showmaxx, Power Champ and Zillarator. The Zilmax in show feeds is far less potent than what is fed to commercial cattle but still adds muscle definition, show participants say. In some cases, manufacturers distribute free samples of medicated feed to youth development groups 4-H or Future Farmers of America, said Richard Sellers, the American Feed Industry Association's vice president for nutrition and feed regulation. The practice is legal - and pragmatic. "You want them to buy feed when they grow up," Sellers said. UNCLEAR RULES Zilmax has not been implicated in any human health problems, according to Merck and a review of FDA records. Only one adverse drug event has been reported to regulators, in which a person who inhaled the drug reported pain, vomiting and difficult breathing. According to the FDA, makers of Zilmax-based show feed products are required to list safe-handling instructions - and tell people to wear appropriate masks, gloves and eye protection when scooping it out to feed to their cattle. Merck includes an FDA-mandated user safety warning on its Zilmax labels. Merck said it shares the wording of the labels with companies that buy Zilmax from Merck to use as an ingredient in their products. The FDA requires any product containing Zilmax to carry this user safety warning, according to FDA officials. In 2012, regulators found that a popular Zilmax show product called Showmaxx was made in a federally unlicensed feed mill and lacked safe-handling instructions on its packaging. Showmaxx marketer XF Enterprises, a nutrition consulting firm in Amarillo, Texas, last year voluntarily recalled Showmaxx. The company did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But the FDA leaves labeling oversight to state regulators, and state officials in cattle-heavy Texas and elsewhere told Reuters the federal Food and Safety Act does not clearly state that such cautionary warnings on these lower-dosage products are required. The FDA disagrees. In practice, feed products have been approved for sale without safe-handling instructions. When Reuters this fall purchased a Zilmax-based feed called Zillarator over the Internet, the product arrived in a plastic bucket that bore no safe-handling instructions. Likewise for another Zilmax-based additive called Power Champ. Manufacturer Suther Feeds Inc of Frankfort, Kansas, said it consulted with Merck on the language used for its label. A state regulator later approved the product's labeling. Merck said in a statement that it provided a copy of a standard label template, including the safe-handling language, to Suther Feed. Michael Johll, chief operating officer of Suther Feeds, said his company adhered to state and federal rules. "If there's something that we've failed to do, we'll do it. I don't believe we have," Johll said. WINNER'S CIRCLES AND DRUG TESTS At the Texas state fair, champion steers routinely fetch six-figure prices at auctions held just after winners' belt buckles are handed out. The same goes for the recent American Royal livestock show in Kansas City, Missouri, or the National Western Stock Show in Denver, Colorado, in January. Slaughterhouses and agribusiness firms often buy the winning steers and market heifers to burnish their brands and encourage youngsters' farming careers. After that, the animals are slaughtered. The zeal at livestock shows can run so hot that there have been drug abuse allegations in the past, though Zilmax has not been implicated. During the 1990s and 2000s, scandals roiled shows in Ohio, Missouri, Colorado and elsewhere when some champion livestock tested positive for clenbuterol, a muscle builder that leaves toxic residues in meat. Now, drug tests are common at livestock shows, with malefactors who use growth hormones, steroids or other unapproved drugs facing lifetime bans. At the Texas state fair last month, collecting a urine sample from a 1,329-pound champion steer named Corndog requires a certain amount of finesse. But veterinarian Dick Shepherd and his animal-health team armed themselves with funnels, specimen cups and patience. "If you're going to let them use anything they want to … you end up with everyone using drugs rampantly," Shepherd said. He was not testing Corndog or other steer for zilpaterol, since the drug has been approved for cattle. Some parents and cattle ranchers want beta-agonist use banned at shows. Arizona rancher Harvey Dietrich, co-founder of advocacy group Beef Additive Alert, said the shows are fueling a culture of short-cuts. But Daryl Real, vice president of the Texas state fair's agriculture and livestock department, shrugs off concerns. The FDA allows Zilmax in beef cattle heading to grocery stores, he reasoned, so contestants should learn to use it, too. Real said most contestants use Zilmax responsibly: Even in Texas, judges don't want steers to be too big. "I liken it to the way I like whipped cream on a dessert," Real said. "A little bit goes a long way. You can have too much whipped cream and ruin the dish." TO USE AND NOT TO USE Supplies of Zilmax show feeds have dwindled since Merck's sales suspension in August. Even so, some Zilmax-based products are still being sold online, and several show contestants told Reuters they had stockpiled their favorite feed additive after Merck's announcement. At the Sandwich Fair in DeKalb County, about an hour west of Chicago, this September, Kendall Nelson, 14, said he was using a Zilmax-based feed this show season. His father, Philip Nelson - a cattle rancher and president of the Illinois Farm Bureau - said he does not use beta-agonist drugs on his livestock. But the younger Nelson began experimenting based on advice from a livestock nutritionist, the father said. The youngster's steers rapidly grew — though they fell short of winning blue ribbons at this year's Illinois State Fair. "It's not dangerous," said Philip Nelson. "If it was, the government wouldn't let it be put it out for sale without a label." Some young competitors say they'd rather win without Zilmax. Ten-year-old Saige Martin of Hereford, Texas, raised her steer Corndog free of beta-agonists, said her father, show cattle breeder Brian Martin. Corndog's closest competitor was a 1,318-pound cross-breed steer named Rojo, and 16-year-old Caitlen Doskocil of Holland, Texas, used a ractopamine feed "to stout him up," said Caitlen's father, Doyle Doskocil. The family's supply of a Zilmax-based feed had run out, he said. Inside the Texas state fair show ring, Corndog - named after the popular American snack because of his coloring - towered over Saige, whose cool smile masked her jitters. A judge slowly circled the steer and ran his hands over the back, feeling for a thick padding of muscle. Corndog impressed, and later was named Grand Champion steer. At auction, he sold for $110,000, a fair record. Saige got a $30,000 check for her college fund - after Corndog passed his drug test. (Reporting By Lisa Baertlein in Dallas and P.J. Huffstutter in Chicago. Additional reporting by Julie Ingwersen and Mike Hirtzer in Sandwich, Ill. Editing by David Greising, Martin Howell and Douglas Royalty)