Lawyers: Free man wrongfully locked up for decades

BAY CITY, Texas (AP) — Attorneys for a Texas man who was kept in prison for more than three decades after his murder conviction was overturned have asked a court to free him so he can get on with his life, saying he's suffered enough from the mishandling of his case and that key trial evidence has gone missing.

Attorney Jeffrey Newberry wrote in a recent court petition that the state clearly violated Jerry Hartfield's right to a speedy trial by waiting decades to retry him for the 1976 death of Eunice Lowe, who was beaten to death at the Bay City bus station where she worked as a ticket agent.

"The most serious prejudice a defendant can suffer in being denied a right to a speedy trial is to have his defense possibly impaired," Newberry wrote. He urged State District Judge Craig Estlinbaum to free Hartsfield "with prejudice," meaning the state couldn't retry him on the same charges.

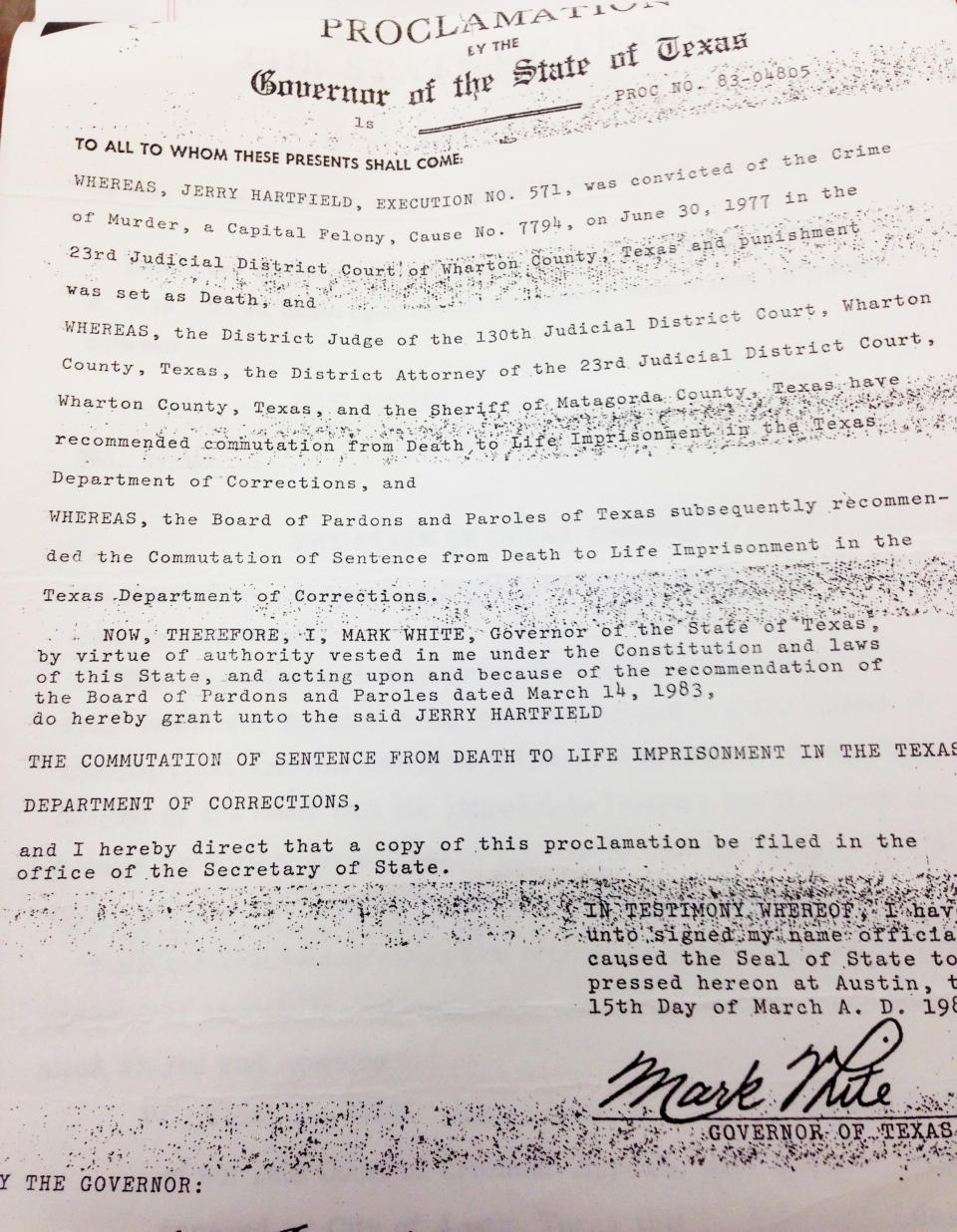

Hartfield, 57, was convicted in 1977 of killing Lowe and sentenced to death, but that conviction was overturned three years later. After prosecutors unsuccessfully appealed that ruling, then-Gov. Mark White commuted Hartfield's sentence to life in prison in 1983.

Hartfield, who is described in court documents as an illiterate fifth-grade dropout with an IQ of 51, didn't challenge his continued detention until 2006, when a fellow prisoner pointed out that once his conviction was overturned, there was no sentence to commute. Appeals courts agreed and ordered Hartfield freed or retried. Hartfield is scheduled to stand trial again in April for Lowe's slaying.

In a court filing, Matagorda County District Attorney Steven Reis rejected the assertion that Hartfield should go free. While acknowledging that the state "may be partially responsible" for the delay in retrying Hartfield, Reis argued that prosecutors didn't act in bad faith and that Hartfield bears some responsibility.

Hartfield "failed to proffer any evidence that he wanted a speedy trial during this period," Reis wrote. No evidence supports a finding that Hartfield "actually wanted a new and speedy trial," that he did anything before 2007 to assert that his right to a speedy trial had been violated, or that the state deliberately acted to delay a retrial, Reis contends.

Newberry contends that the state was solely responsible for the retrial delay.

"Had the state carried out the (appeals court) mandate, Hartfield would not have needed to file the documents that he began filing," he wrote. "Mr. Hartfield has affirmatively demonstrated that his ability to present a defense has been prejudiced by the delay."

Newberry also says authorities haven't been able to find some evidence used to convict Hartfield, including a pickaxe used in the attack or Lowe's car, which was stolen and later recovered. Furthermore, a Texas Ranger who was a key witness for the prosecution at Hartfield's 1977 trial has since died, he wrote.

Estlinbaum asked both sides to address some legal questions before he rules on the matter.

At the time of the killing, Hartfield, who grew up in Altus, Okla., was working construction at nuclear power plant near the bus station where Lowe worked. He was arrested within days of the killing in Wichita, Kan., and was convicted and sentenced to death in 1977.

Hartfield disputes a confession police said he gave them that was among the evidence used to convict him. Prosecutors also had an unused bus ticket found at the crime scene that had his fingerprints on it and testimony from witnesses who said he had talked about needing $3,000. Reis said Hartfield led authorities to Lowe's car in Houston and that his fingerprint was on a piece of broken Dr Pepper bottle found beside Lowe's body.