Let’s talk infrastructure, since Clinton won’t

It’s been a momentous week in politics, what with a former congressman sending more lewd pictures of himself, and Donald Trump invading Mexico, and Rick Perry joining Ryan Lochte on the cast of “Dancing With the Stars,” because apparently his balky back is now completely healed but his dignity is fractured in too many places to count.

But let’s just pause for a moment, as this summer of silliness draws to a close, to consider how the country might actually be governed. Specifically, let’s talk about infrastructure spending.

I know, infrastructure isn’t sexy. But neither is Anthony Weiner, and we’ve talked about him plenty.

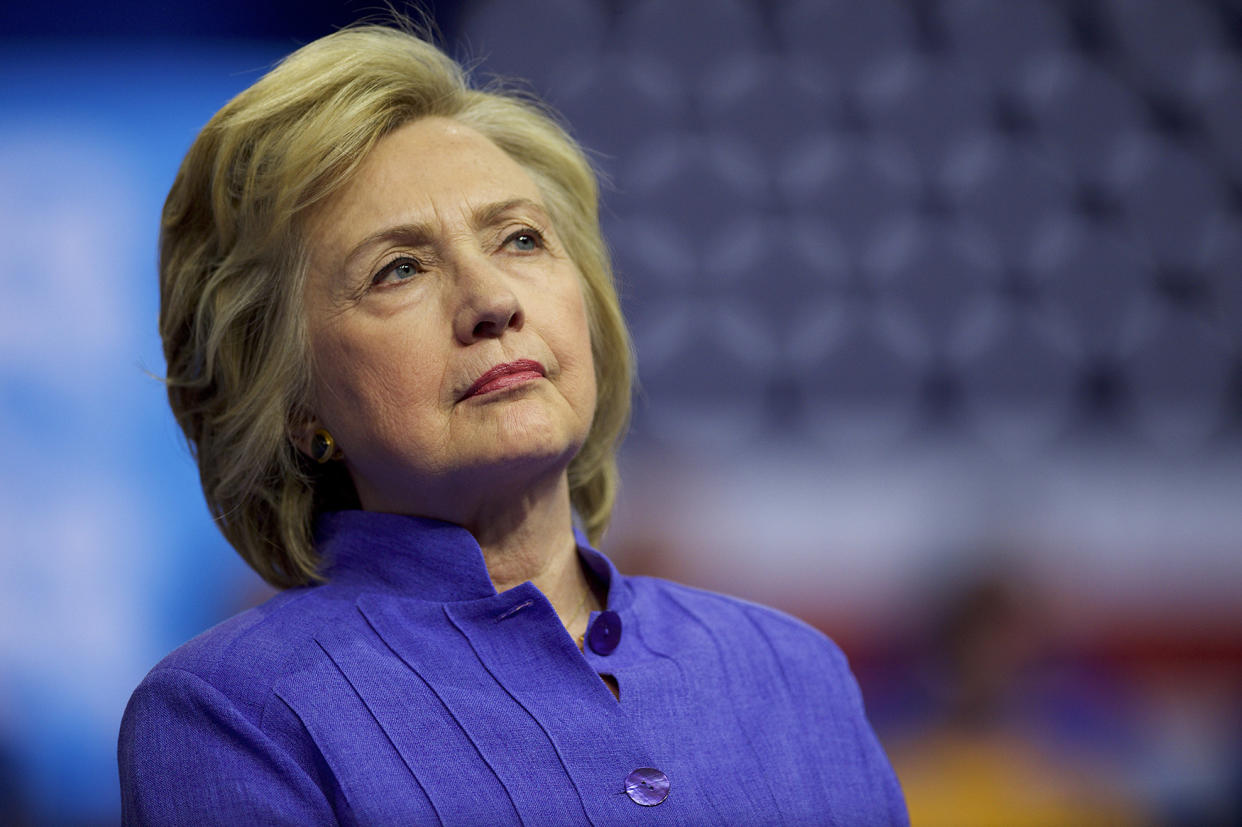

And by taking a closer look at Hillary Clinton’s plan to fix the deteriorating foundation of our economy, you can discern a lot about what she’s getting right in this campaign, and what she isn’t.

Probably nothing the candidates discuss this fall will be more important in the long term than investing in infrastructure. Contrary to what some politicians in both parties will tell you, neither trade policy nor immigration is nearly as critical to determining our economic future.

As you might have heard, the world is ruthlessly competitive now, and increasingly automated, and nothing’s going to roll that back. If you want to attract modern jobs, you have to anticipate and maintain a truly modern society, which is something we’ve only begun to do.

Democrats have talked grandly about infrastructure since at least the mid-1980s, when Gary Hart (yes, there he is again) made something called the Strategic Investment Initiative a centerpiece of his presidential agenda. But when they talk about it, they tend to lapse into New Deal nostalgia, as if the real goal of infrastructure spending was to reach full employment today, and all we had to do was hire legions of workers to go out and build the next big dam or tunnel.

Even President Obama, in successfully fighting for the most significant infrastructure investments in decades, billed his agenda as a kind of Rooseveltian jobs program. As I argued in this New York Times column back in 2010, the administration consciously conflated a short-term employment problem with long-term imperatives, which added to a misperception about what infrastructure spending should actually achieve.

In an important 2011 column for Bloomberg View, Ron Klain, who helped oversee the stimulus spending for the administration (and later served as the “Ebola czar”), made the point that the kind of “shovel-ready” programs we associate with the Great Depression don’t actually create very many jobs nowadays.

That’s because we’ve already built most of our bridges and roads, and even where we haven’t, it takes only a few workers with machinery to do today what it took hundreds of workers to do in the 1930s.

“It’s time to let go of the idea that a handful of marquee construction projects, even majestic and lasting ones, can solve our employment problem,” Klain said. The real point, he wrote, was that long-term investments like those in clean energy and transportation were likely to pay off in the form of jobs for the next generation — something with which a lot of Republicans agree.

Which brings us to Clinton’s $275 billion plan, which she says she will propose in the first 100 days of her presidency. In classic Democratic fashion, Clinton starts by putting infrastructure spending at the center of her short-term “jobs plan” and leads with building roads and bridges, as if we might literally pave our way to prosperity.

But then Clinton quickly pivots to the kinds of investments that really matter in the long run — high-speed rail and public transit, state-of-the-art broadband, highway sensors for driverless cars, high-tech airport and school construction, and so on.

It’s not so much a plan, really, as a sprawling statement of options; Clinton makes no hard choices and assigns no dollar amounts to anything specific. She includes every conceivable avenue of spending and doesn’t get into how she’d pay for any of it, other than a vague nod to “business tax reform.”

But her agenda tilts heavily toward the fast-approaching future, laying out a comprehensive vision of what 21st century America could look like if we made all the investments we need. It’s a proposal very much like Clinton herself: solid, substantive and essentially evasive.

All of which would be fine, even laudable, in the context of a political campaign, except for the fact that she doesn’t have the confidence to elaborate on her vision or sell it to anyone who isn’t already converted.

If you go online to read the long, gauzy summary of the proposal, you’ll find that the campaign also sends you to a speech billed as “Remarks on Investing in Infrastructure During the First 100 Days in Office,” which is in fact a long attack on Trump with a few generic lines about infrastructure. There’s also a link to a bunch of ordinary voters “reacting” favorably to Clinton’s plan, in case that’s helpful.

(Trump, by the way, has airily suggested spending trillions on 1930s-style infrastructure programs, with nothing by way of specifics. Maybe after erecting the wall with Mexico he’s going to build a bridge to Cuba.)

Despite the persistent complaint among aides that campaign coverage is too often about personality and scandal, rather than substance, Clinton declined the chance to be interviewed solely about her infrastructure plan. In my exchanges with the campaign, I didn’t have the sense that anyone even remotely considered it — which probably isn’t surprising, given that Clinton hasn’t faced the press corps in 270 days and counting.

You can see the strategy here, I guess. Why risk a conversation about your actual governing agenda, which might be used against you, while your opponent is out there hemorrhaging credibility every day? Why advance a specific governing argument when all you have to do is step aside and be the less objectionable choice?

I’ll tell you why. Because, as Obama quickly found in 2009, winning an election isn’t an end; it’s a beginning. You still have to govern, and that means you need to have made a sustained public case for the things you actually want to do.

And this, as I’ve pointed out before, is the vital difference between Clinton and her husband. Bill couldn’t wait to convince you he had the right answer to your problem. Hillary, at her core, doesn’t think she can.

If anything, Clinton’s situation would be more complicated than Obama’s, not less. If elected, she’s almost certain to become the first Democratic president in any of our lifetimes to come into office with a Republican-controlled House. It’s safe bet she will not have a 70 percent approval rating or the urgency of a historic economic crisis.

The chances that Clinton would be able to raise taxes or run up the deficit to pay for her plan are pretty much zero. She will have to marshal public support for her agenda, which is more easily done if you start during a campaign than afterward, and which can’t be done if you aren’t willing to talk to the media about the things you claim you want to talk about.

Clinton is right that the country needs a long-term, thoughtful approach to public investment. What it doesn’t need is another president who campaigns on vagueness and too often governs in vain.