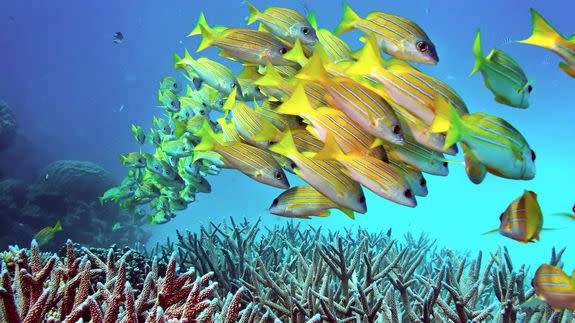

Marine conservation efforts just took a major step forward

Ocean conservation efforts took a significant step forward on Friday when a measure to protect 30 percent of the world's oceans by 2030 passed during a major meeting in Hawaii.

The resolution, which is non-binding, garnered widespread support from the governments and global organizations gathered in Honolulu for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Conservation Congress.

Marine scientists say expanding Marine Protected Areas is essential in order to spare oceans from further destruction and ensure that ecosystems stay healthy enough to adapt to human-caused climate change.

SEE ALSO: Obama visits remote Midway Atoll to highlight climate change threats

"Marine reserves are also climate reserves, and protecting 30 percent of the ocean will ensure local communities are more resilient to climate change," Seth Horstmeyer, a director with The Pew Charitable Trusts' Global Ocean Legacy project, said in a statement after the vote.

The world's oceans produce around half the Earth's oxygen, store about 90 percent of the world's carbon dioxide and encompass a whopping 95 percent of the planet's living space.

Yet marine ecosystems are increasingly at risk because of human activities — from industrial fishing and coastal development to dumping toxic waste, plastics pollution and ocean acidification.

Image: GREGORY BOISSY/AFP/Getty Images

"If we don't ensure the biosphere is intact and well-protected, then we put ourselves at risk over the long-term," Callum Roberts, a professor of marine conservation at the University of York in England, said by phone.

Danny Auron, a campaign director at the non-profit advocacy organization Avaaz, told Mashable the 30-percent target is not only "ambitious and inspiring" but also "the minimum that scientists say we need to survive as a species."

A science-based goal

The 30-percent ocean protection goal is a drastic jump from today's levels, and marks a new achievement for a growing movement to guard against further degradation of marine ecosystems.

The move comes less than a week before the World Oceans Conference in Washington, where U.S. President Barack Obama will give an address.

Less than 4 percent of oceans currently fall within a Marine Protected Area — even with Obama's expansion last month of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Northern Hawaiian Islands.

Image: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images

On Aug. 26, Obama quadrupled the size of the monument to nearly 583,000 square miles, making it the largest protected area of any kind — marine or terrestrial — in the world.

Countries previously set a target to protect 10 percent of oceans by 2012 during the United Nations' Convention on Biological Diversity. They later revised the deadline to 2020 after it was clear the world would miss its original goal.

Proponents of stronger protection measures say the 10-percent target was largely based on politics: It sounded ambitious enough for countries to get behind, but wasn't actually rooted in science.

"We are entirely unrealistic to think that nature can cope with the protection of 10 percent the seas," Roberts, the marine conservation professor, told Mashable.

Roberts and his colleagues reviewed 144 studies to determine whether the 10-percent target was enough to protect global fish populations and keep ecosystems healthy. The average value of those studies was 37 percent of oceans, the researchers said in an April paper published in the journal Conservation Letters.

"What that says is, you have to protect a very significant area of ocean in order to contribute meaningfully to conservation and fisheries management objectives," Roberts told Mashable.

"We're just way out of scale with those targets right now," he said.

Handling the high seas

Countries have a host of economic and strategic reasons for not wanting to rope off their sovereign waters.

Japan, for instance, exports around 1.4 trillion yen ($11.6 billion) worth of seafood each year. New Zealand's offshore oil and gas fields contribute billions of dollars to its economy and tax income. China's controversial artificial islands in the South China Sea bolster its military presence in the region.

But governments' reluctance to establish Marine Protected Areas isn't the biggest challenge to actually achieving the 30 percent by 2030 target.

IUCN Members Assembly: Vote 'YES' On Motion 53 To Support Protection For 30% Of The Ocean! #Protect30 #IUCNCongress pic.twitter.com/wX0C17hohR

— Sylvia A. Earle (@SylviaEarle) September 7, 2016

The largest hurdle will be deciding how to manage protected zones in the so-called high seas — the swaths of ocean that don't fall under the control of state or national governments. Around 65 percent of the oceans falls into this category.

"At some point, you start to run out of waters in the jurisdiction of nations," Horstmeyer said in an interview.

"Ultimately we'll also have to look at the high seas."

While various councils under the United Nations oversee global fishing, mining and shipping activities, no such body exists to manage Marine Protected Areas in the high seas.

"There's no effective means of protecting this common heritage," Lance Morgan, president of the Marine Conservation Institute, told Mashable by phone from the Honolulu summit.

Image: NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Program

The U.N. last year launched a diplomatic process to resolve such thorny questions as: Who can propose a protected area in the high seas? Who is responsible for managing them, and who would foot the bill? Should the U.N. create a new agency just for Marine Protected Areas?

Morgan said that, if all goes to plan, the process should wrap up in 2018, giving countries about 12 years to establish conservation zones before the 2030 deadline.

"That's a pretty good time frame to start doing bigger and more important things," he said.

"With more than 60 percent of the ocean in the high seas, it will be virtually impossible to hit that 30-percent target without a treaty in place to negotiate that."

Despite the deep well of bureaucracy and politics surrounding the new marine conservation target, participants in Hawaii last week said they had felt optimistic — in large part because of the success surrounding the Paris climate change agreement.

Leaders from nearly 200 nations signed a global pact to curb greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, relative to preindustrial levels by 2100.

With the U.S. and China formally signing on this month, the agreement may enter into force by the end of this year.

"There's a feeling that ambitious goals are possible to achieve, and governments are coming to the realization that it's time to actually start moving on these things," said Auron, the Avaaz campaign director.