Mark Woods: Jessie Ball duPont Fund isn't shying away from complicated legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Earlier this year the Jessie Ball duPont Fund brought Ty Seidule, an author and historian, to Jacksonville for a public event.

It was held at the Jessie Ball duPont Center, or The Jessie as the former Haydon Burns Library has been referred to since it was transformed into a nonprofit center at corner of Adams and Ocean (or, as its social media accounts say, “at the corner of conversation and action”).

Seidule, a retired Army brigadier general and former head of the history department at West Point, was there to talk about the personal journey described in his book, “Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause.”

At the end of his talk, Mari Kuraishi, president of the Jessie Ball duPont Fund, read questions that people in the audience had written on notecards. Most of the questions involved Seidule’s story, Confederate monuments and so on.

But Kuraishi got to one notecard and said, “OK, this question is actually for me.”

She read it: Jessie Ball duPont was against desegregation, even actively fought against it. How do you reconcile this with the foundation’s mission?

“Thank you, Bill,” she said with a laugh.

At this point, I expected her to say something along the lines of, “That’s not why we’re here tonight.” But she proceeded to give a nearly 4-minute answer, talking about how this is something those involved with the Jessie Ball duPont Fund have been discussing quite a bit.

Jessie — they often refer to her simply by her first name — was a very generous woman, even before she had lots of money to give away. She also was a committed segregationist. And once she did have money from her marriage to Alfred I. duPont, she used some of it to encourage institutions to “hold the line” against integration.

So, five decades after her death, what should the Jessie Ball duPont Fund do with this?

To a degree, I realized, that was why we were there that night.

It was part of a prominent charitable foundation on its own journey, one that involves grappling, privately and publicly, with a complicated legacy of its founder and funder — and an opportunity for what it describes as “transformative repair.”

So I recently met Kuraishi at The Jessie to learn more.

A lifetime (and more) of philanthropy

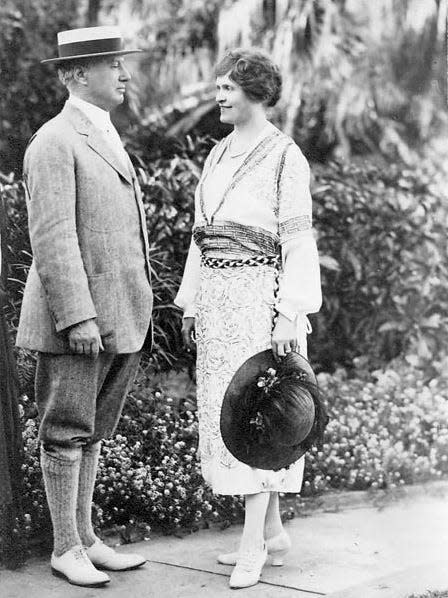

Kuraishi gave a summary of Jessie growing up in rural Virginia in the early 20th century, a distant relative of Mary Ball Washington, the mother of George Washington.

“The Ball family is blue blood and has been in Virginia forever,” she said. “But by the time Jessie is born, the family is no longer a big landowner.”

One of the stories of Jessie’s childhood involves her going around, trying to collect on her father’s bills. She became a school teacher, then a vice principal of a school in California. Even with limited means, she engaged in philanthropy, setting aside some of her own money to give to students she felt should go to college.

Then, at age 39, she became the third wife of one of the richest men in America, Alfred I. duPont. They created a 58-acre estate, Epping Forest, in Jacksonville. He died here in 1935. Jessie, who was 20 years younger, eventually relocated to Delaware and died there in 1970.

Her estate, estimated at $42 million, at the time was one of the largest in Florida history. While today it is a fraction of her husband’s multi-billion-dollar trust, it now is worth about $380 million. And unlike the Alfred I. duPont Testamentary Trust — which has one charitable beneficiary, the Nemours Foundation — it has hundreds of potential beneficiaries.

“She gives a lot during her lifetime,” Kuraishi said. “And our will, which is the founding document of our foundation, says that we can give to the entities she gave to between 1960 and 1965, for any reason whatsoever. There are some 300-plus organizations on that list. We can also give for the temporary relief of people in need in Florida, Delaware and Virginia. That's really what the will says and not much else.”

So when Kuraishi became Jessie Ball duPont Fund president in 2019, one of the questions they pondered was both simple and complex: What are we really about?

“There isn't any explicit guidance in the will,” she said. “ It doesn't say, ‘You will support education.’ …. I think it's not unreasonable to say that we are in the business of creating communities of belonging in the places and institutions that Jessie loved.”

Another question was: What to make of that complicated legacy?

It isn’t that Jessie Ball duPont’s beliefs in white supremacy and integration were hidden. They’re part of a biography, published more than 30 years ago. But in recent years, the foundation has quite purposefully dug deeper into Jessie’s writings, even hiring a historian to go through the extensive archives.

“We don't want to be the ones to say, ‘Oh, I didn't know that,’” Kuraishi said. “We need to be the world's experts on Jessie. So we've been spending a lot of time trying to figure out, ‘What's out there? Let's let's make sure we know everything.’”

Kuraishi says that when you look at Jessie’s list of grantees in that 1960 to 1965 window, especially in higher education, they skew very much toward schools where she could strengthen a resolve against integration. And when you read her letters — and she wrote a lot — she explicitly explains why she was supporting places like the University of the South.

“She writes to these institutions: You must hold the line against integration,” Kuraishi said.

This isn’t to say Jessie donated only to whites-only institutions. She also gave money to historically Black colleges such as Edward Waters and Bethune-Cookman, and other Black institutions. But in the 1960s — the same decade that attempts to integrate lunch counters in Jacksonville led to Ax Handle Saturday — she clearly was pushing for, and actively supporting, continued segregation. In some instances, she ended her financial support for organizations after they integrated.

So what to do with that today?

Acknowledge, reconcile, repair

In a time when we see efforts to avoid uncomfortable conversations about the past, to stick to simple versions of history, the Jessie Ball duPont Fund — its board of trustees and leadership team — hasn’t shied away from this question. They’re having an ongoing conversation about it, one that has led to three guiding words: acknowledge, reconcile, repair.

Acknowledge the past. Reconcile in the present. Repair for the future.

This includes supporting some of the same places Jessie did, like the University of the South and Stratford Hall (the birthplace of Robert E. Lee), as these places are on their own journeys, reckoning with their pasts, evolving for the future.

Another example is in Virginia. In the wake of the Supreme Court desegregation ruling. Prince Edward County didn’t integrate its public schools. It closed them. A whites-only segregation academy was established. That was one of the schools that Jessie Ball duPont supported. And for five years, there weren’t any schools in the county for Black students in the county.

So, acknowledging playing a part in the harm done there then, today the Jessie Ball duPont Fund provides scholarships for Black students at the former segregation academy, now known as the Fuqua School.

All of this has led to another question: Is the Jessie Ball duPont Fund going to change its name?

The answer, at least for now, is no. As it says on its website: “In part because bearing Jessie’s name puts us in the position of acting both to repair the harm that was caused by her actions, and to continue enhancing the good that has come from her commitment to doing good.”

“And” is a key word. Like when Kuraishi says: “Jessie was an amazingly generous woman and she was a segregationist.”

Both things can be true. Both things are true. And they lead to the questions the foundation has been asking itself, questions that other institutions also have been asking themselves.

Kuraishi describes a sculpture at Princeton University devoted to one of the school’s presidents, Woodrow Wilson. “Double Sights,” as the piece by artist Walter Hood is titled, includes some of Wilson’s accomplishments as U.S. president, like leading efforts to create the League of Nations. It also includes him re-segregating the federal government and showing “Birth of a Nation” in the White House.

That sculpture, installed five years ago, was intended to start a conversation about what the school describes as the “complex legacy” of Wilson. And while obviously there are differences between the life of Jessie Ball duPont, there are some similarities in the conversations.

For the Jessie Ball duPont Fund, those conversations have led to a continued commitment to the places Jessie loved — and to acknowledging, reconciling and repairing her legacy.

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jessie Ball duPont Fund grapples with philanthropist's legacy