McCutcheon: Should the rich speak louder?

National Constitution Center President and CEO Jeffrey Rosen looks at the arguments made by two powerful voices about the First Amendment, its role in campaign financing, and the constitutional requirement to make government more responsive to all of the people.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court handed down its most important decision on campaign finance reform since Citizens United. The decision, McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, seemed to divide along familiar ideological lines, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing the majority opinion for five conservatives and Justice Stephen Breyer, writing the dissent for the four liberals.

What really divided the court, however, wasn’t partisan politics pitting Republicans against Democrats but two conflicting views of the First Amendment. Which view you embrace depends on whether you see the McCutcheon decision as a principled triumph for unpopular speech or a First Amendment disaster that will ensure that a handful of the richest Americans can use their vast resources to drown out the voices of everyone else.

The First Amendment view embraced by Roberts and his conservative colleagues is rooted in individual liberty. There’s no right in our democracy more fundamental, Roberts began, than the First Amendment safeguards for “an individual’s right to participate in the public debate through political expression and political association.”

People exercise both these rights when contributing to candidates, Roberts said, whether they are a “lone pamphleteer” or someone who spends “substantial amounts of money.” He maintains that Congress may not “restrict the political participation of some in order to enhance the relative influence of others.”

The First Amendment that Breyer and the liberal dissenters embrace is far different. Breyer objected that Roberts’s focus on “the individual’s right to engage in political speech” fails to account for “the public’s interest in preserving a democratic order in which collective speech matters.”

Breyer explained that crucial civic discourse can be overwhelmed by the inequalities of wealth. “Where enough money calls the tune,” Breyer wrote,” the general public will not be heard.” That’s why he stressed “the constitutional importance of Congress’ concern that a few large donations not drown out the voices of the many.”

Both views of the First Amendment are plausible. They point, however, in very different directions. Roberts insisted that individual free expression and association is so important that only evidence of quid pro quo corruption — for example, trading votes for money — can justify limiting it. Breyer’s emphasis on collective political participation led him to fault the court for defining corruption too narrowly, and ignoring the Founders’ concern that representatives are responsive to all of “We the People” — not just the wealthy few.

What’s significant about this debate is that neither Roberts nor Breyer denied that the contributions of the wealthy few have the potential to drown out the voices of the less wealthy many.

But Roberts insisted that the First Amendment doesn’t allow Congress to address the problem by requiring the wealthy to turn down the volume. He said Congress instead must use alternatives to restricting speech — such as disclosure laws — that critics say are ineffective or unrealistic.

A similarly surprising consensus emerged Wednesday in a podcast about the McCutcheon decision between Floyd Abrams, the leading civil libertarian liberal defender of Citizens United and the Roberts view of free speech, and Lawrence Lessig, the leading crusader against what he calls the “dependence corruption” that makes candidates dependent on their richest donors to the exclusion of everyone else.

Abrams agreed with Lessig that “wealthy people have the power to communicate much more than people who don’t have money.” This influence can come in two ways: the voices of the wealthy can influence the public debate by paying for a barrage of ads or push polls more than those who can’t afford ads and push polls while at the same time, because money buys access and influence, candidates are likely to pay more attention to their most generous contributors.

Abrams disagreed only with Lessig’s proposed solution — limiting spending by the rich to reduce their likelihood of influencing elections or candidates. Inequality of wealth is a social problem, Abrams said, but “a core lesson of the First Amendment is that we deal with social problems at our best in ways that don’t limit freedom of expression” — such as changing the tax or anti-trust laws.

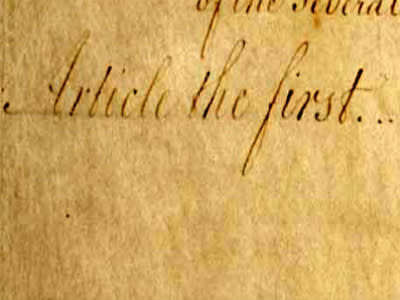

Lessig, like Breyer, countered that far from forbidding efforts to prevent the rich few from drowning out the voices of the less rich many, the First Amendment requires it. “The majority opinion,” Lessig said, “is contrary to the idea of creating a democracy where the government is responsive to the people. He continued, “A conception of corruption that doesn’t allow Congress to achieve the objections of representative democracy” — where Congress is dependent on all the people not just the rich — violates the Framers’ original understanding.

Lessig and Abrams, whose debate was hosted by the National Constitution Center, agreed that the McCutcheon decision would be unpopular with a majority of Americans. But, Abrams insisted, this is the price of the First Amendment.

Roberts made a similar point in his majority opinion. “If the First Amendment protects flag burning, funeral protests and Nazi parades — despite the profound offense such spectacles cause — it surely protects political campaign speech despite popular opposition,” he said.

Those who oppose the Supreme Court decisions striking down campaign finance reform but support First Amendment protections for unpopular speech need to respond to Roberts’ and Abrams’ challenge It is not enough to say these decisions undermine elections because the voices of the powerful few drown out the voices of the less powerful many — since neither conservatives nor liberals dispute that.

The stronger response is that the speech of the rich has the potential to make the people’s representatives less dependent on the people themselves. The Framers of the First Amendment might well have concluded that far from forbidding Congress’s efforts to make government more responsive to all the people, the Constitution requires it.

Jeffrey Rosen is the CEO and president of the National Constitution Center, and also the legal affairs editor of The New Republic. The article first appeared in “The Great Debate” opinion section of Reuters.com.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Constitution Check: What will the next challenges be to limits on money in politics?

Podcast: Floyd Abrams and Lawrence Lessig on the campaign finance decision

Reaction to the Supreme Court’s historic campaign financing decisione