Mexico's left in disarray ahead of election

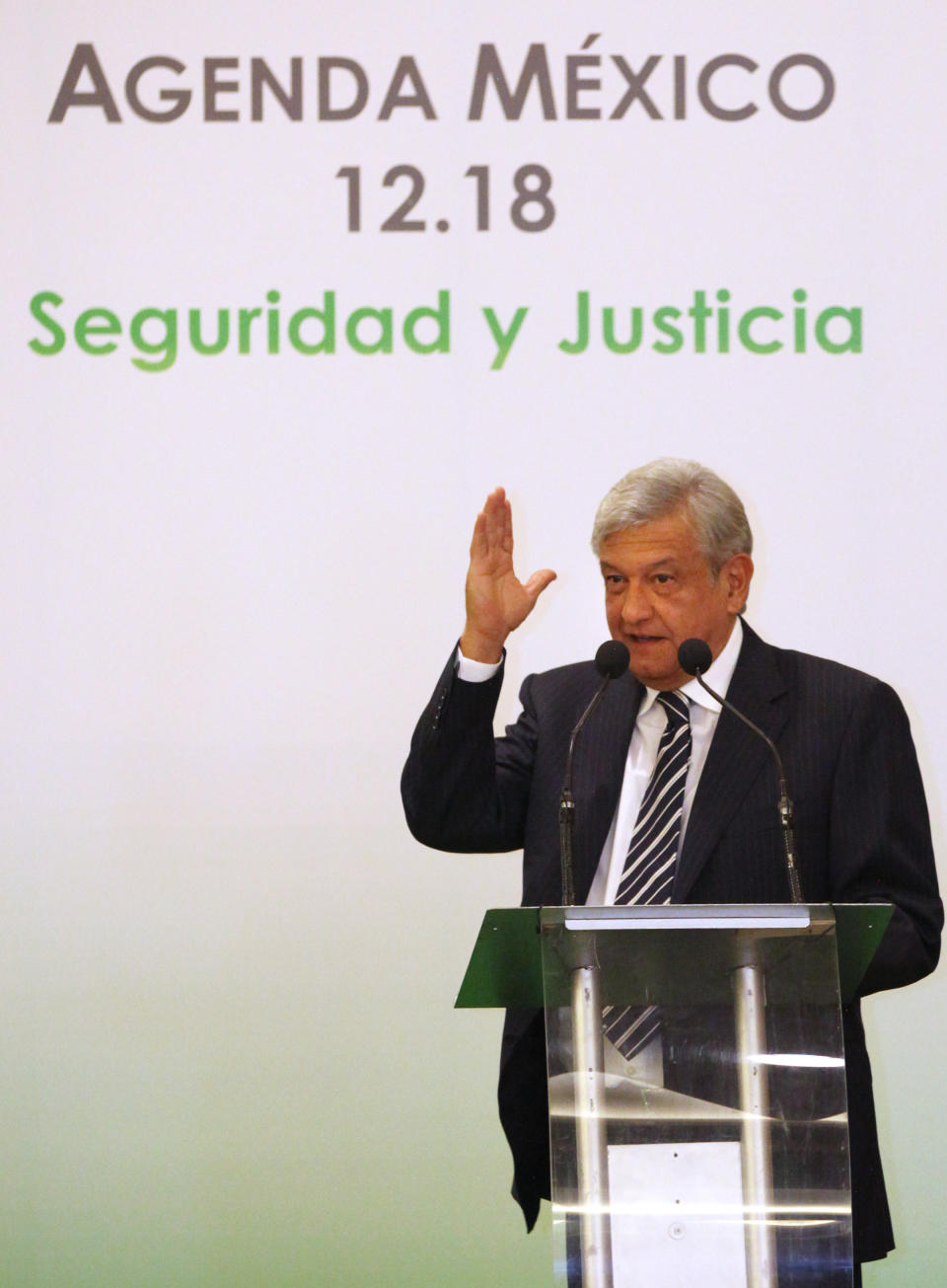

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has left behind his image as an angry leftist for what he's calling his "Republic of Love" campaign in a second try for the Mexican presidency.

The left's candidate for the July 1 election has adopted the slogan "Abrazos, No Balazos," or "Hugs, Not Bullets," putting forth a warmer persona, a more business-friendly platform and an anti-crime program that relies largely on increased jobs and education programs.

But while Mexicans appear ready to boot out the ruling center-right National Action Party, or PAN, it's not Lopez Obrador's Democratic Revolution Party they are turning to for change. Instead, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which governed Mexico for 71 uninterrupted years before the PAN nabbed the presidency in 2000, suddenly looks new, with a fresh-faced candidate and a strong lead in the polls.

And it's Lopez Obrador, and Mexico's left, that look old.

Mexicans voted for change 12 years ago when they tossed out the long-ruling PRI, which had been accused of electoral fraud, repression and economic mismanagement, and chose PAN candidate Vicente Fox, a rancher and former Guanajuato state governor. The conservative party barely retained the presidency in 2006 when its candidate Felipe Calderon won a narrow victory that Lopez Obrador insisted was his. His enraged supporters blocked Mexico City's center for weeks to demand a vote-by-vote recount.

But Lopez Obrador's move to a gentler center this time around may not have been enough for a Mexico that has seen nearly 50,000 people killed in drug violence since the last presidential contest.

He has changed his tune from the 2006 campaign, when the slogan was, "For the good of all, the poor first." Lopez Obrador now courts the middle class and independent businessmen who say Mexico needs a break from the big monopolistic corporations that came to dominate the country under the PRI and the PAN.

"The only ones who have grown are the 20 families involved in monopoly enterprises," said cement importer Ricardo Alessio Robles, "while we, the 6 million independent businessmen, are paying them overly high prices and not growing as much as we could."

It's the kind of strategy that could have put Lopez Obrador over the top in 2006, but now seems tardy.

"It may be late, because if he had done it six years ago, without doubt he would have won," said Manuel Camacho Solis, a former Mexico City mayor who was among Lopez Obrador's campaign coordinators in 2006 and now leads an informal coalition of leftist parties.

Camacho Solis said that for Lopez Obrador it had been "a hard decision, given his personality and political history ... but he realized he had to move to the center, because the left alone was not sufficient to win power."

Six years ago, Lopez Obrador was known for his confrontational stance, and for the supporters who paralyzed downtown Mexico City to protest Calderon's victory.

Lopez Obrador now spends a lot of time apologizing for that.

He's also made some moves uncharacteristic of Mexico's old left, meeting with U.S. Vice President Joe Biden and attending a Mass by visiting Pope Benedict XVI in March, along with the other leading candidates. Lopez Obrador is now courting businessmen, a group his party would have scorned in the past.

But although there was no question he was one of the top two candidates in 2006, this time he's running third in the polls behind even the ruling party.

Certainly, appearances play a role: Lopez Obrador is 59, while front-runner Enrique Pena Nieto of the PRI is 45 with movie-star looks. But it goes beyond age. The left still looks to the past, analysts say, fighting old battles such as its losses in 1988 and 2006 elections it says were marred by fraud.

One of Lopez Obrador's campaign videos features him apologizing for the disruptive protests he mounted after his narrow 2006 loss; another starts out with black-and-white footage of the 1910 Revolution and past election campaigns.

The left — and Lopez Obrador's PRD party — seem out of touch with today's Mexico. Although the PAN has had limited success in governing over the past 12 years, it has changed the political discourse in important ways.

Distrust of the United States, hostility to organized religion and reliance on state-owned industries were among issues that served for decades as the touchstones of Mexican politics, with the left clinging to them long after they were abandoned by the PRI, which had championed them after assuming power following Mexico's Revolution.

Although those issues have since been pushed into the background, Lopez Obrador still largely bases his economic recovery program on the notoriously inefficient state-owned oil company, Pemex, and he wants to restore a state-owned power company that had largely been controlled by a notoriously corrupt union.

Such views lead political analyst Roger Bartra to refer to Mexico's "conservative, at times frankly reactionary left."

"It is a tragic paradox," Bartra he said.

Campaign ads for Lopez Obrador feature photos of the 1910-1917 Mexican Revolution.

"The very concept of revolution is now something that in Mexico sounds old, conservative," Bartra said. "The result is a left that has no clear direction, hasn't modernized, and continues to be trapped in an old-style nationalism."

The left has also been caught flat-footed by key developments over the last decade in Mexico. While still poor, the country is home to an increasingly powerful middle class, whose political loyalty, unlike peasant masses or unionized workers, is hard to win through government handout programs.

Experts and political insiders say the left in Mexico is also hobbled by what was once its greatest strength: reliance on a single charismatic figure whose personality overshadows the political platform.

While Lopez Obrador has now run twice for the presidency, his party predecessor, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, ran three times in a country where experts widely agree that voters give a politician only one shot at the highest office in the land.

And as it did six years ago, Mexico's fractious left has had difficulty uniting itself in an electoral front. It is comprised of dissidents from the PRI, opportunists who fled to the PRD to get nominations denied them in the formerly long-ruling party, democratic socialists and ex-communists.

All that has helped blur the left's ideological appeal; most of the state governors elected on a PRD ticket in recent years have been ex-PRI members who hold little in common with the left-leaning party.

Alejandro Granillo, a 26-year-old Mexico City drug store employee, said he's leaning toward not voting or annulling his ballot.

"Lopez Obrador does have a bit more connection with the people than the others," Granillo said. "But what is his anti-crime program? I don't think you're going to solve the problem with love."