Military's first Black bomb disposal expert went 'from the cotton fields to the Pentagon'

When Sherman Byrd was a kid in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s, his three older brothers would sometimes throw him into a lake, just to see if he could it make back to shore. They weren't about to let him drown but perhaps, they figured, they might be able to discourage him from hanging out with them so much.

But he soon got his revenge, his family recounted. It turned out he could swim, and swim well, and he could hold his breath for what seemed like forever. So when the older boys would chuck him in again, he'd stay under — longer and longer — until they panicked and jumped in, searching for him. And he'd just pop up elsewhere, laughing.

Their parents were sharecroppers, hard-working but poor. Their father took to making bootleg liquor in the woods, trying to get ahead, and just ended up in jail, more than once.

That was no life for the Byrd boys. So the three older brothers joined the Army. But when Sherman was 17, he — the swimmer — took his own path. He signed up for the Navy.

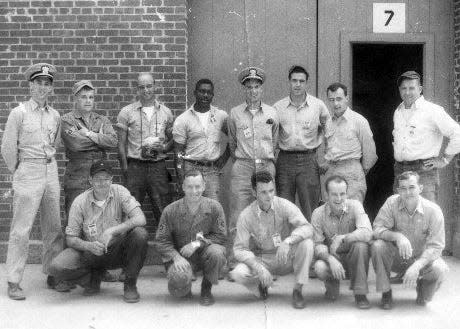

That was the day after Christmas 1947, the year before the military became integrated by race. Byrd was Black, and not someone to shy away from challenges. So he sent money home to his mother, volunteered for risky jobs and rose up the ranks, making the Navy his life, his too-short life.

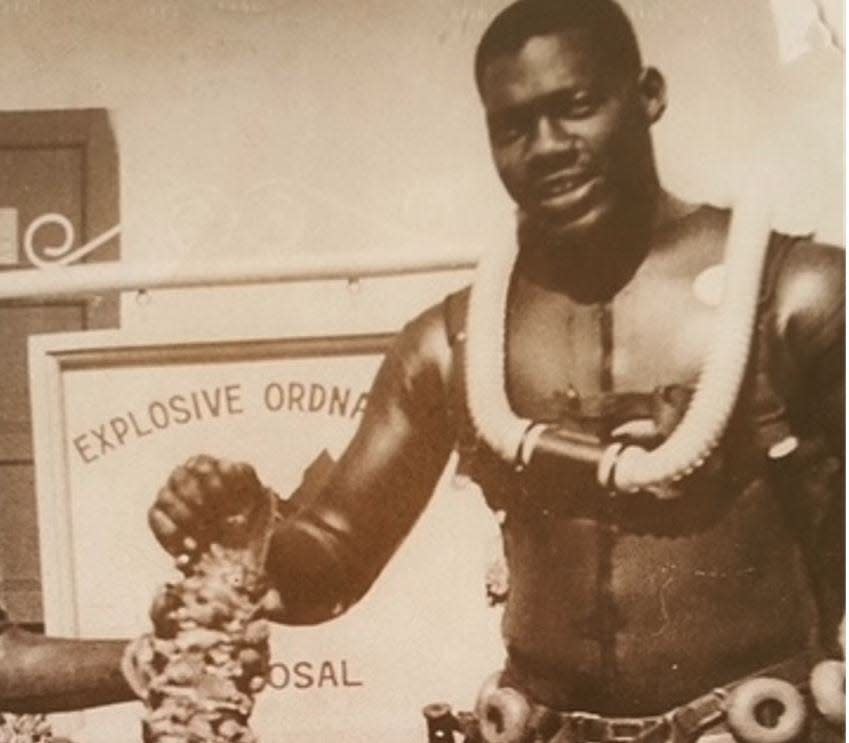

After serving on several ships, he faced significant racism and skepticism as he volunteered to train as a deep-sea diver for the Navy and graduated in 1955, according to his family and the Navy. He wanted more though. So he volunteered to become a bomb disposal expert, graduating from the challenging Explosive Ordnance Disposal program in 1958 — and becoming the first Black EOD technician in the military.

In 1964 he became an EOD instructor at a base in Maryland and five years later was promoted to master chief boatswain's mate.

Honored at the Pentagon

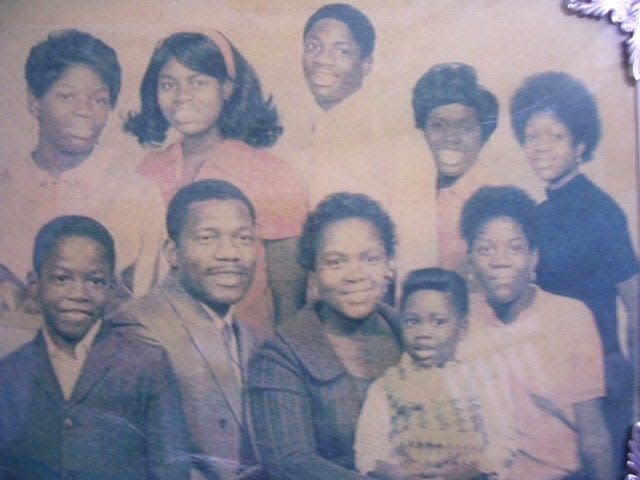

Byrd and his wife, Louise, had eight kids together, and they didn't tell them anything about his work with bombs. "He would always just say, 'I'm a deep-sea diver in the Navy and I'm very good at what I do,'" said his youngest daughter, Cynthia Byrd Conner. "That was it."

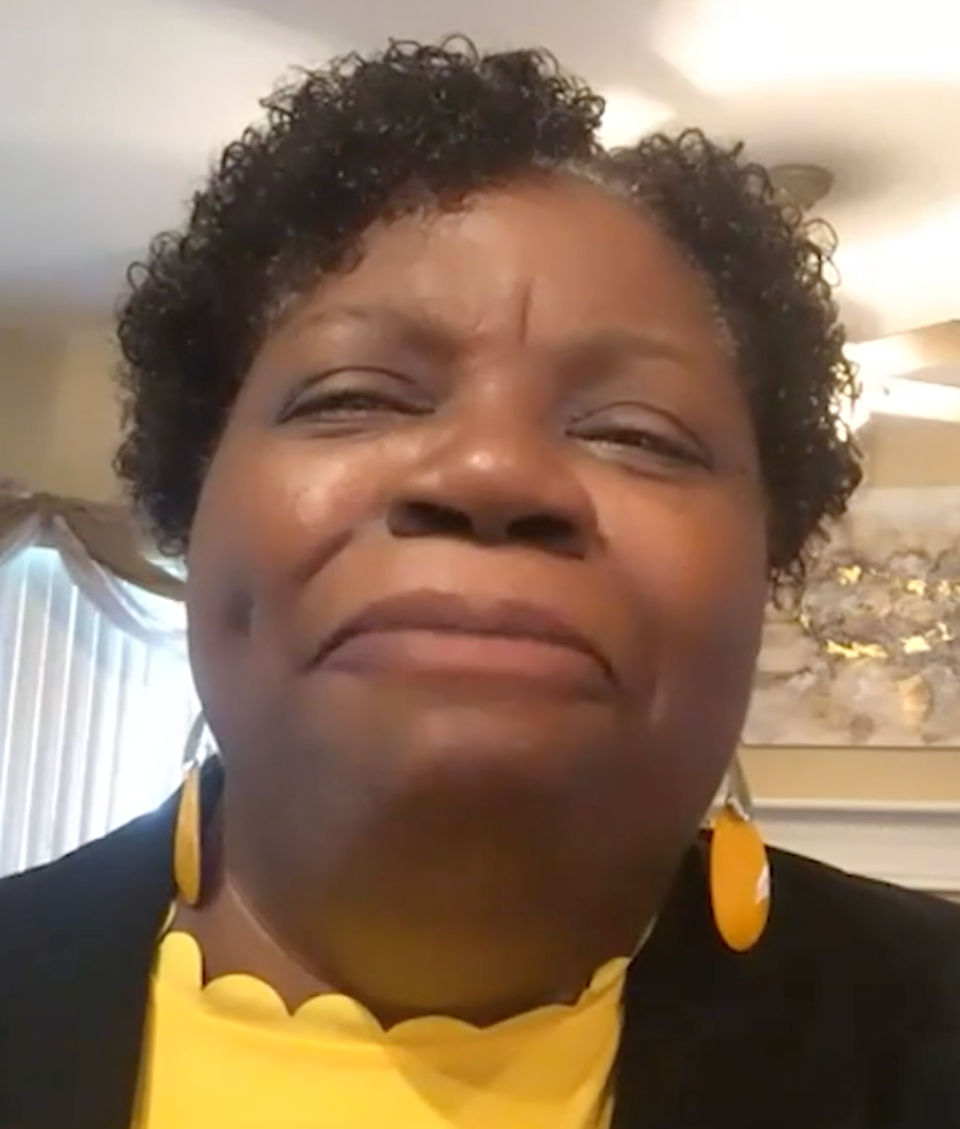

Conner supposes her parents didn't want them to worry and said her mother didn't once say anything about it, even though she lived 30 years longer than her husband. It wasn't until the Navy put Byrd's name on an EOD training facility in Virginia Beach, Va., that the children, now all grown, found out.

Byrd would be honored again, in 2022, with a resolution from the City Council in Jacksonville, where Conner lives. She's retired from a civil service position at Southeast Regional Maintenance Center at Mayport.

And just a few weeks ago, Byrd was honored once again, this time in the halls of the Pentagon where his story is told in an exhibition dedicated to the military's bomb disposal experts.

Conner, 66, who wrote the book "Quiet Strong, based on her father, traveled from Jacksonville to the opening. It was, she says, a "forever moment" being in that building and seeing the reverence and respect shown her father by present-day EOD technicians who were there.

"They were amazed at him, and I was amazed by them," she said, trying to describe the feeling. "It was like amazement in the atmosphere.”

She was joined by numerous relatives and is touched by memory of four elderly family members in wheelchairs, seeing the honor paid Sherman Byrd.

"Just to see the joy in their eyes, that one of their relatives had gone from the cotton fields to the Pentagon,” she said.

An early death

Conner was 13 when her father died in 1971. Her family lived in a close-knit Black community in Portsmouth, Va., called Cavalier Manor, just a short distance from the home of Navy diver Carl Brashear, a friend of the family whose story was told in the 2000 film "Men of Honor" starring Cuba Gooding Jr. and Robert DeNiro.

Conner was walking home one day when a boy, her next-door neighbor, said her father had a heart attack.

"I looked at him and said, 'Not my dad. I thought my dad was invincible," she said. "I would be the one on the playground saying my dad could jump tall buildings, my dad is the strongest, my dad is the fastest."

But it was true. He had collapsed at a training exercise. A few days later, he died in the hospital.

When he died, his daughter was at the house of her lifelong friend, Renee Stukes, spending the night to make room for relatives who'd come from all over. Her friend's mother, Vivian, woke her gently at 5 a.m., rubbing her forehead, telling her only that her mother had called a family meeting and she needed to be home right away.

Her friend's father, Alphonso, drove her the few blocks to her house in the early morning. She'll never forget: She could hear her mother screaming from five houses away.

She knew then that her father was gone.

Remembrances and facing down racism

Conner remembers going to meet her father with her mother and siblings when his ship came home. The family would make a sign or practice a song to greet him. And they could see him coming off the ship, carrying big baby dolls for his daughters. Some sailors would tease him, but he didn't mind. “If it made his girls smile, he was all for it," she said.

She remembers how when he came home, he would sometimes open the garage door, sit on a lawn chair, have a drink and watch the world go by. Her mother would say don't mess with him for a while. It was, Conner thinks, a way of decompressing from the pressures of his work, and the family respected it.

She remembers how meticulous his uniforms were, which carried over to his personal dress — creases in his pants, neatly polished shoes.

She remembers how he was a perfectionist and how he expected good behavior from his children. Even at the grocery store, her mother would get compliments on how the children dressed, how well they behaved.

“I think he set goals for himself, to improve in his career and to keep going, and I also think that he understood the weight of being a Black man and knocking down the ceiling for those who would come after them," Conner said.

Prisoner of War: With diary revealed, Jacksonville woman tells of reticent father's life as a POW in Germany

She remembers how he never mentioned to her about how he had to face prejudice, though in conversations later with his brother Ned, Conner learned some of what he'd gone through: How some sailors didn't want Black sailors to train in the same pool, how they were thought to be diseased, to have gonorrhea or syphilis.

As he moved up in the ranks, he supervised white sailors, some of whom weren't happy about that. "He had to tell white people what to do; they weren’t warming up to that," Conner said. She learned, though, that some of his white superior officers had set them straight. Respect the rank, they insisted.

“From what I could glean from Uncle Ned, he stood his ground," Conner said, "but it was hard to face resistance on a daily basis.”

Wyley Wright: Documentary chronicles Jacksonville veteran’s story

And she remembers her father's quiet dignity and how he tried to pass that on.

“That generation of people really took seriously their jobs," she said. "They wanted to show that they were Americans and they loved their country, and whatever another nationality could do, African Americans could do also. They were a quiet generation. They suffered quietly. I never once heard my dad come home and say, those white people get on my nerves, or this is so unfair, I can’t get a break. I never heard that. He would come home and say, whatever you want to be in life, you can be. And if you fall, get up and try again. “

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: First Black Navy diver and bomb disposal tech is honored by Pentagon