Modi campaign stirs religious divide in India's heartland

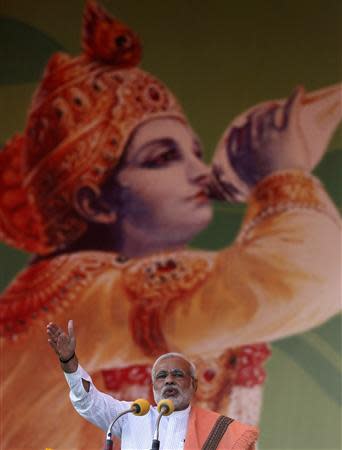

By Mike Collett-White and Sharat Pradhan AGRA, India (Reuters) - Prime ministerial hopeful Narendra Modi used a large rally in India's historic city of Agra on Thursday to push his Hindu nationalist agenda in a key election state where the sizeable Muslim minority eyes his campaign with alarm. With a bigger population than Russia and 80 parliamentary seats up for grabs, the northern state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) is seen as a must-win battleground for Modi in a national election expected to start by April. The rally in Agra, where tens of thousands of people filled a dusty field outside the center of the city that boasts the Taj Mahal, was Modi's fourth visit to the state in the last month or so, underlining its importance. The 63-year-old, whose grueling campaign has put him in pole position to lead the world's biggest democracy, attacked the ruling Congress party for pandering to minorities - making indirect references to majority Hindus and minority Muslims. "They are ... neglecting 75 percent of the people and playing games for 25 percent of the people," he shouted from a large stage decorated in the saffron color of his opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). "Doing injustice to 75 percent of the people is all they have done," he said to cheers from a rowdy crowd where very few Muslims were visible. Most of India's 150 million Muslims eye Modi with deep suspicion, after Hindu mobs killed at least 1,000 people, most of them Muslims, in religious riots in the western state of Gujarat in 2002, when he was chief minister. Modi has been accused of turning a blind eye to the violence, or even encouraging it, but he rejects any blame. PROVOCATIVE MOVE In a provocative move criticized by Congress, the BJP rally honored two politicians accused by police of fanning clashes in September in the UP town of Muzaffarnagar, where Hindus and Muslims fought street battles and more than 50 people died. Local lawmakers Sangeet Som and Suresh Rana, who deny any wrongdoing and who have been released on bail, were welcomed to the stage, garlanded with flowers and presented with white scarves and colorful headgear, to loud applause. But in a sign that the BJP wants to distance Modi from the violence while at the same time appealing to his core constituency, they were ushered off stage before he arrived. Since becoming the BJP's prime ministerial candidate 10 weeks ago, Modi has softened his image by avoiding the emotive language of "Hindutva", a hardline brand of Hindu nationalism. Other speakers on stage were less circumspect, however, with local BJP leader Ram Pratap Singh Chauhan calling Congress, and two regional parties aligned with it in UP, "anti-Hindu". "That is why we need someone like Modi in India, to stop the appeasement of Muslims," he said. "Small countries like Pakistan ... are issuing threats because we are unable to take action. Narendra Modi is a man who is capable of breaking anyone's jaw if it comes to that." All major parties have traditionally sought to exploit religious and caste loyalties to win votes in UP, where the BJP won only 10 seats in the last national ballot in 2009 and is believed to need around 40 to have a chance nationally. Modi has traveled the length and breadth of India addressing huge crowds and electrifying Indian politics with speeches that combine economic promises, a focus on local issues and ridicule of the Gandhis who control the Congress party. In Agra, he spoke of the need to do more to attract tourists and to provide clean water to a city where supplies are short. "If our government is formed, I can promise you we will bring development to this country which will change the lives of your children ... change the lives of the poor," he said. Despite the momentum behind his campaign, political analysts believe Modi will struggle to conquer UP. "In Uttar Pradesh, the BJP has seen a tremendous decline," said Sudha Pai, professor at the Centre for Political Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. "I don't think one individual can make that much difference," she said, while cautioning that India's fractured political landscape makes predictions difficult. (Writing by Mike Collett-White and Frank Jack Daniel; Editing by Alistair Lyon)