Moving work by Colin Firth anchors 'Railway Man'

There are, of course, different ways to make war movies. Some are sweeping, some more intimate. Some are visceral and raw, and some take a more understated approach.

There are moments that "The Railway Man," starring Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman and directed by Jonathan Teplitzky, feels like a period TV drama — slow, subtle, a bit distant — but that doesn't detract from the ultimate power of its story, which is both remarkable and true. It also doesn't detract from Firth's nuanced and ultimately quite moving performance, as well as an admirable turn by the talented Jeremy Irvine as a younger version of the same man. (Kidman, on the other hand, feels somewhat wasted in an underwritten part.)

"The Railway Man" is based on the autobiography of Eric Lomax, a British Army officer who was brutally tortured at a Japanese POW camp during World War II. Lomax somehow survived — unlike many fellow soldiers — but came home broken and haunted, particularly by his ordeal at the hands of one sadistic Japanese interpreter. In his book, Lomax, who died in 2012 at age 93 (during editing of this film), chronicles what happened when he was able to confront the interpreter in person, many years after the war's end.

Without giving away too much, the final resolution is both stunning and cathartic, and the movie conveys its full emotional resonance — even if it takes a long while to reach that level of intensity.

The "railway" in the title refers to more than one thing. As a child, we learn, Lomax was enthralled by trains. During the war, trains became a source of agony as he and his comrades, in captivity in Thailand, were forced to work under inhuman conditions on the infamous Death Railway, built by the Japanese with forced labor to link Bangkok with Rangoon, Burma.

But Lomax's fascination with trains endured. We first meet him in 1980 at a veterans' club in northern England, seemingly a shell of a man, who spends his time obsessing with train timetables. In a train compartment one day, he meets Patti (Kidman), who promptly starts bringing him out of his shell. It's a pleasure to see Lomax's reserve slowly melt and reveal some of his inner charm. And revealing charm, we know, is something Firth does very well indeed.

Soon the two are married, apparently ready for middle-aged happiness. But Lomax is a damaged man, and war flashbacks show us why.

The young Lomax (Irvine, terrific at portraying courage and fear all at once) is a resourceful soldier, and he uses his talents to secretly build a radio receiver so that he and fellow POWs can get news of the war in Europe. It works, but when the radio is discovered, retribution against Lomax is swift and terrible. Waterboarding is part of his torture regimen, at the hands of the merciless Nagase (played by Tanroh Ishida as a young man).

Back in the 1980s, Lomax struggles with the memories, which make him both desperate and bitter toward Patti. She seeks answers from her husband's war buddy, Finlay (Stellan Skarsgard), who has his own demons. It's Finlay who discovers one day that Nagase is alive and in fact giving tours at the very spot in Thailand where the men were tortured. Finlay begs Lomax to take revenge.

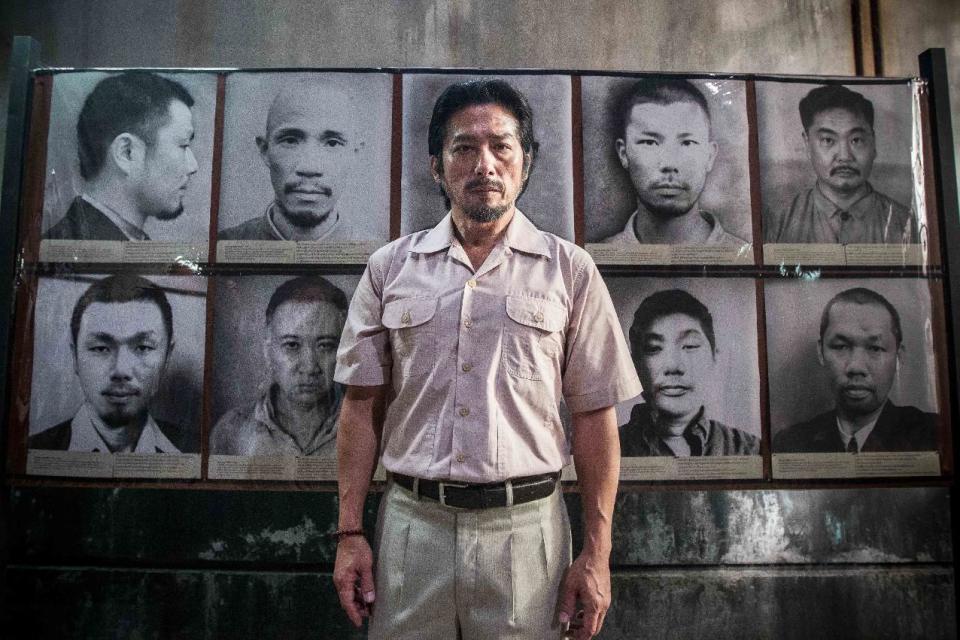

Lomax makes the trip, and Firth comes alive in these scenes, battling rage and a thirst for vengeance with a gradual understanding that war may have ruined both men equally. "Maybe we both lived for this day," one man says to the other. (Hiroyuki Sanada is very effective as the older Nagase.)

Somehow, even if you already know the story, the climax feels, if not unexpected, at least fresh, when it could have easily been schmaltzy.

But you may need those tissues when the real-life photos of the men suddenly appear as the credits roll. That brief moment is as moving as any in the film.

"The Railway Man," a Weinstein Company release, is rated R by the Motion Picture Association of America "for disturbing prisoner of war violence." Running time: 108 minutes. Three stars out of four.