How athletes from Kings players to Olympic athletes now openly embrace mental health

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Professional athletes are familiar with being dehumanized. They know fan react angrily at players having a bad game. They are aware their performances affect fantasy participants who see their teams hurt by performances. They have a sense of bettors losing on parlays. They know they performances are captured in data.

They can be treated as commodities more than humans. Players’ emotions often don’t get factored in.

But athletes also dehumanize themselves. They set their emotions aside, bottling them up at times, draining energy to avoid the dreaded word those in team sports hope to never embody: “distraction.”

The conversation surrounding distractions and mental health has changed dramatically over the last decade. Some are going against convention and working hard to embrace their struggles, even doing so publicly, to set an example for others and welcome an era of vulnerability so the next wave of athletes can maximize their performance with unshackled minds.

New Sacramento Kings star DeMar DeRozan has become a key figure and champion of the evolving discussion surrounding mental health. He made waves with a 2018 tweet during All-Star weekend in his home town of Los Angeles, putting a spotlight on his depression despite having a successful NBA career countless people strive for.

This depression get the best of me...

— DeMar DeRozan (@DeMar_DeRozan) February 17, 2018

DeRozan later revealed his father, Frank, battled illness for three years. But beyond a two-game absence from NBA games during the weeks before his father’s passing in February 2021, few knew of what DeRozan felt underneath his basketball armor. Later he would open up about the mental health issues he was carrying, joining a prominent group of athletes to discuss openly the challenges mental health issues such as depression and anxiety can create.

That group includes Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps, NBA player Kevin Love, tennis player Naomi Osaka and former 49er and current Jets defensive lineman Solomon Thomas.

It also includes gymnast Simone Biles, who dropped out of the Tokyo games three years ago because she suffered from the “twisties,” a state of mental confusion that left her feeling disoriented while she was airborne in her routines. She was open about how she couldn’t perform, not because of a physical issue but one of the mind.

She has returned to the floor in the Paris, ready at 27 physically, and now mentally, one more time. Her two-part Netflix series dropped this month examining her preparation.

Olympic athletes now speak more openly about not only their coaches, families, but therapists. Mental health has become more mainstream in sports, teams have prioritized it to take care of their players and maximize performance, including the Kings.

‘Mental health issues are real’

“Mental health issues and mental toughness are mutually exclusive events, and mental health issues are real,” said Dr. Ethan Bregman, a sports psychologist at West Coast Counseling and Sport Psychology in Sacramento. “And I think it’s actually phenomenal that some of the elite athletes out there as role models almost open permission to take care of oneself.”

While dealing with his difficulties, DeRozan realized he didn’t need to shield his mental health issues to avoid being a distraction to his teammates and coaches.

“It just showed you the stigma that was behind it, of people not wanting to talk or put their feelings out there in the open, feeling like they didn’t want to be a distraction or be a ‘Debbie Downer,’” DeRozan said after his introductory news conference in early July. “Me, just finding power in doing that, went a long way.”

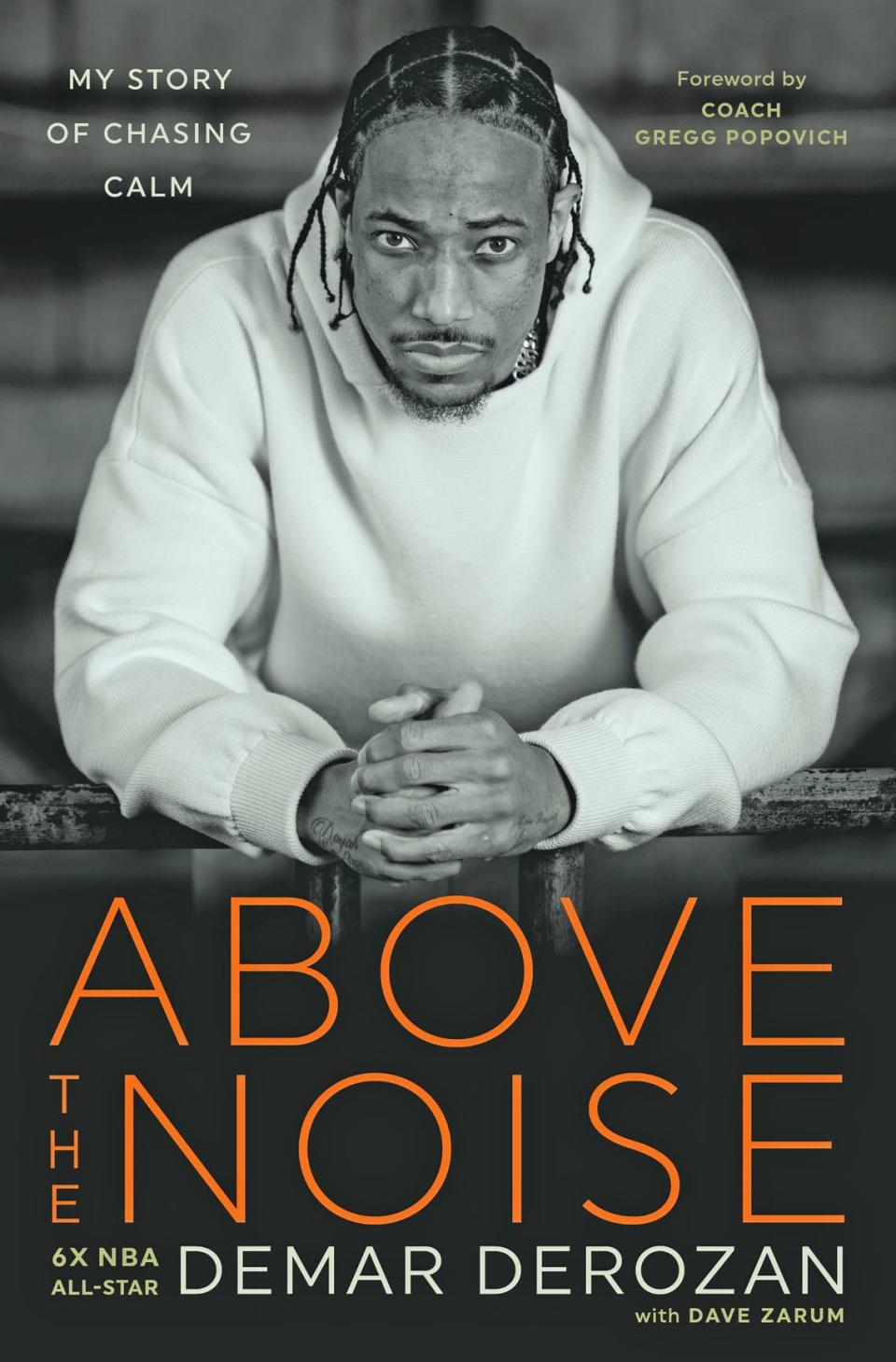

DeRozan has become outspoken about the importance of mental health with his 2018 Tweet as a jumping off point. He has a popular YouTube series, Dinners With DeMar, where he discusses mental health with other NBA stars, and a book publishing Sept. 10 called “Above the Noise.”

Looking back, DeRozan, 34, wish he could have changed the way he thought about mental health earlier in his career as he battled depression.

“It made me more frustrated,” he said, “because it was like, ’damn, I wish I would have been doing this.’ Not just for myself but for others as well that feel the same way of not wanting to express what was really going on. For me, just putting myself out there, (it was) having a hope that it helped others.

“And it definitely went a long way long further than ever in life I could have imagined.”

Younger people focus on mental health

Bregman began working with athletes in his practice in 2010 and said he felt he worked with more youth athletes as time progressed.

“So that was kind of unexpected, an unexpected surprise,” he said. Some of it was driven by parents, and some by the youth athletes themselves, he said.

A study from Gallup and the Walton Family Foundation last September found that about 41% of Gen Z people aged 18 to 26 considered themselves “thriving,” while 60% of millennials at the same age were thriving. The study suggested members of Gen Z are significantly more likely to reveal feelings such as stress, anxiety or loneliness than older generations.

The differences in approaches to mental health among different age groups could also apply to sports.

“There was a time when saw depression as, ‘hey, just pull yourself up by your boot straps and deal (with it),’” Bregman said. “And we’ve learned over time that isn’t how it actually works. And so when it comes to athletes, we’ve often have this view that athletes are so mentally tough — if you’re so mentally tough you don’t deal with depression, anxiety and these other kinds of mental health issues.”

Bregman said many of the youth athletes he works with are specialized in their respective sports, rather than playing different sports in different seasons. They often starting at 4 or 5 years old. Many play year round with private coaches, which is often parent driven.

“Ten-year-olds, 12-year-olds talking to me about wanting D-1 scholarships, not even knowing what that actually means,” Bregman said, noting that some youth athletes he knows have experienced anxiety. “Is that coming from the child’s expectation? Is that coming from parental expectation of the child? Is that coming from parental pressure around the expectations of achievement in sport? Without the data, it’s hard to say, but that’s what I see a lot of.

“It’s something at the beginning of my practice I didn’t really see coming.”

One thing athletes of all ages can relate to is having to perform under pressure. It applies the same to DeRozan trying to get his team to the NBA playoffs, Biles or Phelps trying to win an Olympic medal or a teenager hoping to perform well enough to earn a college scholarship.

“You think about athletes, we often conceptualize them as these super human people who don’t have problems,” Bregman said. “Athletes are humans. They have the same issues and struggles and difficulties as the rest of us. However, then we add in this layer of incredible, incredible pressure that’s on the scene now. Whether it comes from social media, whether it comes from athletes getting better so the bar keeps getting raised as to what constitutes elite performance.

“So when we’re talking about athletes who have this extra huge layer of pressure,” Bregman continued, “when they’re also struggling with mental issues ... depression makes it hard to function for anybody, let alone the ability to function at elite levels.”

Victory in vulnerability

Graham Betchart has been a mental performance coach for athletes for over 20 years. He spent the last two with the UCONN Huskies men’s basketball team that won the last two NCAA championships, and also spent a season with the Sacramento Kings when they ended their 16-year playoff drought in 2023.

One of Betchart’s ethos, which mirrors what DeRozan discovered after revealing his depression, is the success that comes with athletes being vulnerable and acknowledging the issues they face, head on, rather than using energy to suppress emotions.

“If you have a story in your head that says, ‘I don’t want to bring this up because I don’t want to bother somebody,’ that’s choking,” Betchart said. “This idea that we’re not allowed to say our feelings, that’s the deadly thing.”

Betchart used to work with Celtics star Jaylen Brown. He pointed to discussions he had with Brown that he said helped change his mind set. Brown was named Finals MVP when Boston beat the Dallas Mavericks in five games.. Brown wore a microphone during Game 2 and the ABC broadcast showed him telling teammates about the challenge: “Breathe into it, accept it,”

Bretchart said Brown was practicing what he called “proactive mental skills training,” which was different than DeRozan’s, which were more reactive to previous feelings.

“You heard him saying in the Finals saying, ‘lean in, feel uncomfortable, trust.’ He’s embracing the vulnerability,” Betchart said.

The work Betchart teaches to athletes is part of the growing movement emphasizing mental fitness as if it were just as important as physical fitness.

“If I’ve been avoiding vulnerability, that’s essentially avoiding lifting weights in the weight room,” he said. “We were taught being tough is avoiding vulnerability when being tough is allowing vulnerability.”

The payoff in showing vulnerability for DeRozan came from many people outside of the sports world. He said after discussing his depression and mental health publicly he heard from countless people who were positively impacted.

“It’s all been all types of walks of life that came to me and expressed so much to me that I never would have imagined,” DeRozan said. “It’s been people who weren’t even basketball fans but understood the mental part of it and had a struggle from that aspect that brought them to me.

“So it shows you how far it goes even outside the sports field. To me that’s what really sticks out.”