Biden’s bid to fix a broken Supreme Court: It’s time to get political

On Monday, President Joe Biden unveiled a package of reforms targeting the United States Supreme Court. That package included a proposal to amend the Constitution to reverse the Supreme Court’s recent decision granting the president of the United States immunity from criminal prosecution for acts undertaken in their official capacity.

Biden dubbed that proposal “The No One Is Above the Law Amendment.” He said, “It would make clear that there is no immunity for crimes a former president committed while in office.”

A White House statement explained that the amendment Biden wants adopted “will state that the Constitution does not confer any immunity from federal criminal indictment, trial, conviction, or sentencing by virtue of previously serving as President.”

An article in The Hill rightly notes, “When the nation’s high court hands down a ruling on a constitutional issue, the judgment is virtually final, and decisions can only be altered with a constitutional amendment and a new ruling.”

Yet prospects for passage of Biden’s proposed amendment are bleak, with House Speaker Mike Johnson saying that it would be “dead on arrival” in the House of Representatives. Johnson's response could hardly have come as a surprise to the president or anyone who regards the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. United States as a constitutional abomination.

But Biden was right to propose the amendment. He was right to say that it would be consistent with “our Founders’ belief that the president’s power is limited, not absolute. We are a nation of laws — not of kings or dictators.”

He was right to offer the American people the chance to exercise their ultimate authority over the Constitution and its meanings.

And the president's desire to amend the Constitution to correct the court’s presidential immunity decision is also consistent with our history. Several times in the past the Constitution has been changed to overrule a Supreme Court decision.

Before looking at that history, let me see a little bit more about what Biden is proposing.

The president is building on an effort that began last week when New York Congressman Joe Morelle, the top Democrat of the Committee on House Administration, first introduced his own version of a constitutional amendment to undo the presidential immunity decision. Like Biden, Rep. Morelle was unsparing in his criticism of the Court.

“Earlier this month,” Morelle said, “the Supreme Court of the United States undermined not just the foundation of our constitutional government, but the foundation of our democracy. At its core, our nation relies on the principle that no American stands above another in the eyes of the law.”

“I introduced this constitutional amendment,” Morelle continued, “to correct a grave error of this Supreme Court and protect our democracy by ensuring no president is ever above the law. The American people expect their leaders to be held to the same standards we hold for any member of our community. Presidents are not monarchy, they are not tyrants, and shall not be immune.”

The amendment Morelle introduced states that “No officer of the United States, including the President and the Vice President, or a Senator or Representative in Congress, shall be immune from criminal prosecution for any violation of otherwise valid Federal law, nor for any violation of State law unless the alleged criminal act was authorized by valid Federal law, on the sole ground that their alleged criminal act was within the conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority of their office or related to their official duties.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

It exempts Senators and Representatives who are protected by the so-called Speech and Debate Clause of the Constitution. That clause states, “for any Speech or Debate in either House, they [members] shall not be questioned in any other Place.”

Morelle’s amendment also tries to clarify the limits of the president’s pardon power. “The President,” it says, “shall have no power to grant a reprieve or pardon for offenses against the United States to himself or herself.”

More than 40 Members of Congress are co-sponsoring Rep. Morelle’s constitutional amendment, including such well-known figures as Representatives Jamie Raskin, Pramila Jayapal, Barbara Lee, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Rashida Tlaib. So far, no Republicans have signed on.

In the Senate, Democrat Mazie Hirono has released a discussion draft of the text of an amendment like Biden’s and Morelle’s.

These proposals are just the latest in many uses of the amendment process to deliver a rebuke to the Supreme Court. Such uses go back almost to the founding of the country itself.

Reviewing that history, law professor John Orth explains there are “two ways to reverse a U.S. Supreme Court decision by constitutional amendment. The first type of amendment may reverse the decision by instructing the Court on the proper construction of a particular provision, as in the case of the Eleventh Amendment.”

That amendment, which was adopted in 1795, states: “The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.” It was adopted to overturn Chisholm v. Georgia, which allowed a citizen of South Carolina to sue the state of Georgia to recover a debt.

As Orth explains, since the adoption of the 11th Amendment, “much has been made of the phrase ‘shall not be construed.’ The Supreme Court has interpreted the phrase to mean that the Amendment was intended to restore the original understanding of the grant of federal jurisdiction rather than to alter or amend the text.”

The second way to reverse a Supreme Court decision is to pass an amendment altering or adding to the constitutional text rather than just changing the construction of an existing provision. The example Orth gives is the 16th Amendment.

Adopted in 1913, that amendment reversed an 1895 Supreme Court decision holding that a federal income tax was unconstitutional. It, Orth observed, “provided express constitutional authorization for a tax on incomes.”

The amendment supported by Biden, Morelle, and Hirono would fall into the second category. It would join such other corrective amendments as the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, passed in the wake of the Civil War, both of which reversed the Supreme Court's infamous Dred Scott decision by abolishing slavery and granting citizenship to freed slaves.

Recently, the 24th Amendment overruled the Court’s 1937 decision in Breedlove v. Suttles that upheld the constitutionality of the poll tax. And in 1971, the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age to 18 in both state and federal elections. It overturned a Supreme Court decision, Oregon v. Mitchell, that said Congress had no authority to set the voting age in state elections.

Each of these amendments is evidence of why, as Harvard’s Jill Lapore argues, “The Framers believed that ‘No single article of the Constitution is more important [than Article V the provision allowing for amendments] because if you couldn’t revise a constitution, you’d have no way to change the government except by revolution.’”

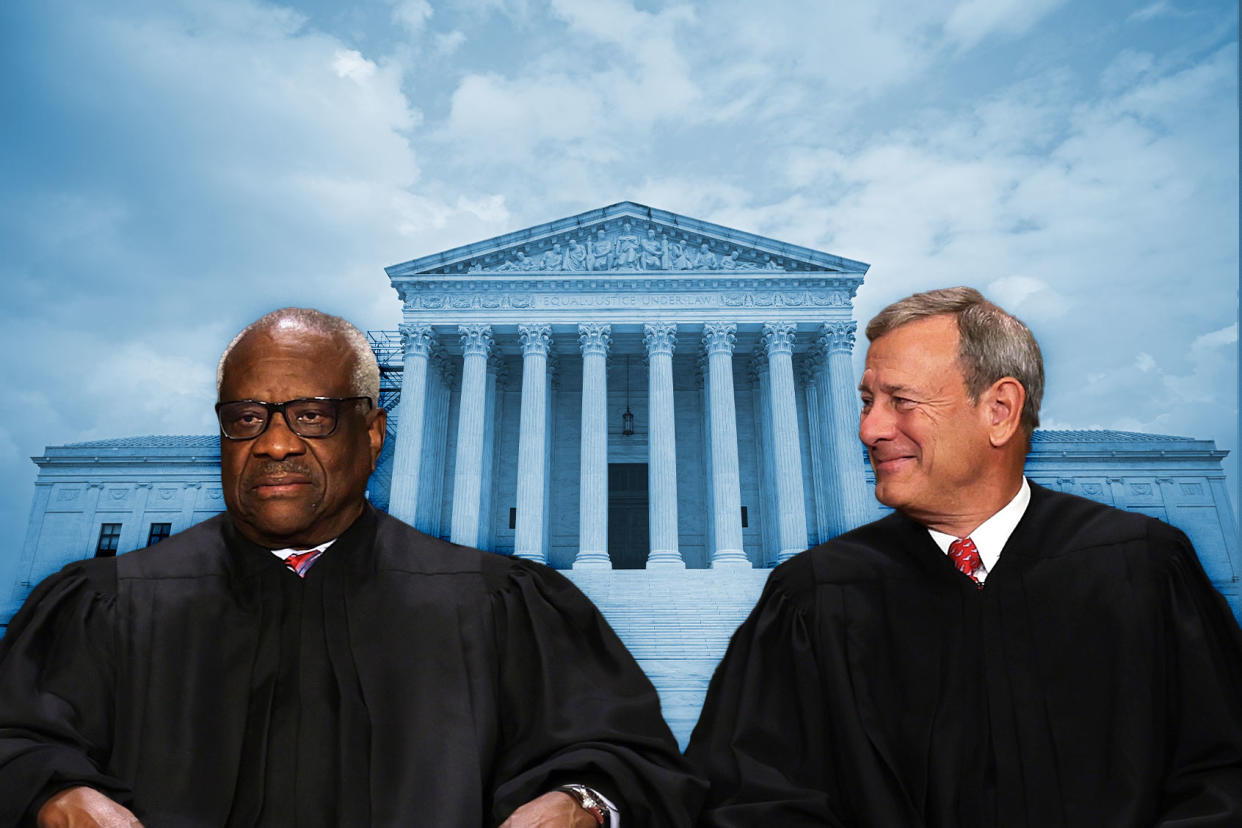

And what Biden is now proposing is an important reminder that the final authority over the meaning of the Constitution rests with the people of the United States, not nine people in black robes who sit on the Supreme Court. Whatever happens to the efforts to use the amendment process to undo the presidential immunity decision, that is a lesson worth remembering.